שמות 1:15–22

וַיֹּ֙אמֶר֙ מֶ֣לֶךְ מִצְרַ֔יִם לַֽמְיַלְּדֹ֖ת הָֽעִבְרִיֹּ֑ת אֲשֶׁ֨ר שֵׁ֤ם הָֽאַחַת֙ שִׁפְרָ֔ה וְשֵׁ֥ם הַשֵּׁנִ֖ית פּוּעָֽה׃

וַיֹּ֗אמֶר בְּיַלֶּדְכֶן֙ אֶת־הָֽעִבְרִיּ֔וֹת וּרְאִיתֶ֖ן עַל־הָאבְנָ֑יִם אִם־בֵּ֥ן הוּא֙ וַהֲמִתֶּ֣ן אֹת֔וֹ וְאִם־בַּ֥ת הִ֖וא וָחָֽיָה׃

וַתִּירֶ֤אןָ הַֽמְיַלְּדֹת֙ אֶת־הָ֣אֱלֹהִ֔ים וְלֹ֣א עָשׂ֔וּ כַּאֲשֶׁ֛ר דִּבֶּ֥ר אֲלֵיהֶ֖ן מֶ֣לֶךְ מִצְרָ֑יִם וַתְּחַיֶּ֖יןָ אֶת־הַיְלָדִֽים׃

וַיִּקְרָ֤א מֶֽלֶךְ־מִצְרַ֙יִם֙ לַֽמְיַלְּדֹ֔ת וַיֹּ֣אמֶר לָהֶ֔ן מַדּ֥וּעַ עֲשִׂיתֶ֖ן הַדָּבָ֣ר הַזֶּ֑ה וַתְּחַיֶּ֖יןָ אֶת־הַיְלָדִֽים׃

וַתֹּאמַ֤רְןָ הַֽמְיַלְּדֹת֙ אֶל־פַּרְעֹ֔ה כִּ֣י לֹ֧א כַנָּשִׁ֛ים הַמִּצְרִיֹּ֖ת הָֽעִבְרִיֹּ֑ת כִּֽי־חָי֣וֹת הֵ֔נָּה בְּטֶ֨רֶם תָּב֧וֹא אֲלֵהֶ֛ן הַמְיַלֶּ֖דֶת וְיָלָֽדוּ׃

וַיֵּ֥יטֶב אֱלֹהִ֖ים לַֽמְיַלְּדֹ֑ת וַיִּ֧רֶב הָעָ֛ם וַיַּֽעַצְמ֖וּ מְאֹֽד׃

וַיְהִ֕י כִּֽי־יָרְא֥וּ הַֽמְיַלְּדֹ֖ת אֶת־הָאֱלֹהִ֑ים וַיַּ֥עַשׂ לָהֶ֖ם בָּתִּֽים׃

וַיְצַ֣ו פַּרְעֹ֔ה לְכל־עַמּ֖וֹ לֵאמֹ֑ר כל־הַבֵּ֣ן הַיִּלּ֗וֹד הַיְאֹ֙רָה֙ תַּשְׁלִיכֻ֔הוּ וְכל־הַבַּ֖ת תְּחַיּֽוּן׃

And the king of Egypt spoke to the Hebrew midwives, of whom the name of the one was Shifra, and the name of the other Pu῾ah: and he said, When you do the office of midwife to the Hebrew women, you shall look upon the birth stones; if it be a son, then you shall kill him: but if it be a daughter, then she shall live. But the midwives feared God, and did not as the king of Miżrayim commanded them, but saved the men children alive. And the king of Miżrayim called for the midwives, and said to them, Why have you done this thing, and saved the men children alive? And the midwives said to Par῾o, Because the Hebrew women are not as the Egyptian women; for they are lively, and are delivered before the midwives come to them. Therefore God dealt well with the midwives: and the people multiplied, and grew very mighty.

In a remarkable act of defiance, the Hebrew midwives Shifra and Pu’ah refused to murder the baby boys that they delivered. For this, they have ever since been evoked in discussions of Jewish midwifery, which is the topic of this week’s Talmudology on the Parsha.

Abaye’s Midwife-Surgeon

In Masechet Shabbat, the great Babylonian amora Abaye (d.337) described the skill of his nurse, (whom he called אם, mother, for she raised him). She was both a midwife and a surgeon, as this passage makes clear:

אָמַר אַבָּיֵי, אֲמַרָה לִי אֵם: הַאי יָנוֹקָא דְּלָא יְדִיעַ מַפַּקְתֵּיהּ, לְשַׁיְיפֵיהּ מִישְׁחָא וְלוֹקְמֵיהּ לַהֲדֵי יוֹמָא, וְהֵיכָא דְּזִיג — לִיקְרְעֵיהּ בִּשְׂעָרְתָּא שְׁתִי וָעֵרֶב. אֲבָל בִּכְלִי מַתָּכוֹת — לָא, מִשּׁוּם דְּזָרֵיף

Abaye said: my nurse told me: In the case of a baby whose anus cannot be seen, [as it is obscured by skin,] let one rub it with oil and stand it before the light of the day. And where it appears transparent, let one tear it with a barley grain widthwise and lengthwise. However, one may not tear it with a metal implement because it causes infection and swelling.

This midwife was also skilled in a number of other post-natal interventions:

וְאָמַר אַבָּיֵי, אֲמַרָה לִי אֵם: הַאי יָנוֹקָא דְּלָא מָיֵיץ, מֵיקַר [הוּא] דְּקָר פּוּמֵּיהּ. מַאי תַּקַּנְתֵּיהּ? לַיְתוֹ כָּסָא גּוּמְרֵי, וְלַינְקְטֵיהּ לֵיהּ לַהֲדֵי פּוּמֵּיהּ, דְּחָיֵים פּוּמֵּיהּ וּמָיֵיץ. וְאָמַר אַבָּיֵי, אֲמַרָה לִי אֵם: הַאי . יָנוֹקָא דְּלָא מִנַּשְׁתֵּים — לִינְפְּפֵיהּ בְּנָפְווֹתָא וּמִנַּשְׁתֵּים

וְאָמַר אַבָּיֵי, אֲמַרָה לִי אֵם: הַאי יָנוֹקָא דְּלָא יְדִיעַ מַפַּקְתֵּיהּ, לְשַׁיְיפֵיהּ מִישְׁחָא וְלוֹקְמֵיהּ לַהֲדֵי יוֹמָא, וְהֵיכָא דְּזִיג — לִיקְרְעֵיהּ בִּשְׂעָרְתָּא שְׁתִי וָעֵרֶב. אֲבָל בִּכְלִי מַתָּכוֹת — לָא, מִשּׁוּם דְּזָרֵיף. וְאָמַר אַבָּיֵי, אֲמַרָה לִי אֵם: הַאי יָנוֹקָא דְּלָא מָיֵיץ, מֵיקַר [הוּא] דְּקָר פּוּמֵּיהּ. מַאי תַּקַּנְתֵּיהּ? לַיְתוֹ כָּסָא גּוּמְרֵי, וְלַינְקְטֵיהּ לֵיהּ לַהֲדֵי פּוּמֵּיהּ, דְּחָיֵים פּוּמֵּיהּ וּמָיֵיץ. וְאָמַר אַבָּיֵי, אֲמַרָה לִי אֵם: הַאי יָנוֹקָא דְּלָא מִנַּשְׁתֵּים — לִינְפְּפֵיהּ בְּנָפְווֹתָא וּמִנַּשְׁתֵּים.

Abaye said: My nurse told me: If a baby refuses to nurse, that is because its mouth is cold and it is unable to nurse. What is his remedy? They should bring a cup of coals and place it near his mouth, so that his mouth will warm and he will nurse. And Abaye said that my mother told me: A baby that does not urinate, let one place him in a sieve and shake him, and he will urinate.

And Abaye said: My nurse told me: If a baby is not breathing, let them bring his mother’s placenta and place the placenta on him, and the baby will breathe. And Abaye said that my mother told me: If a baby is too small, let them bring his mother’s placenta and rub the baby with it from the narrow end to the wide end of the placenta. And if the baby is strong, i.e., too large, let them rub the baby from the wide end of the placenta to the narrow end. And Abaye said that my mother told me: If a baby is red, that is because the blood has not yet been absorbed in him. In that case, let them wait until his blood is absorbed and then circumcise him. Likewise, if a baby is pale and his blood has not yet entered him, let them wait until his blood enters him and then circumcise him.

As we will shortly see, this ability to both deliver babies and operate on a number of neonatal conditions was common among Jewish midwives.

Ancient Roman midwife attending a woman giving birth. From TheWellcome Trust Corporate Archive.

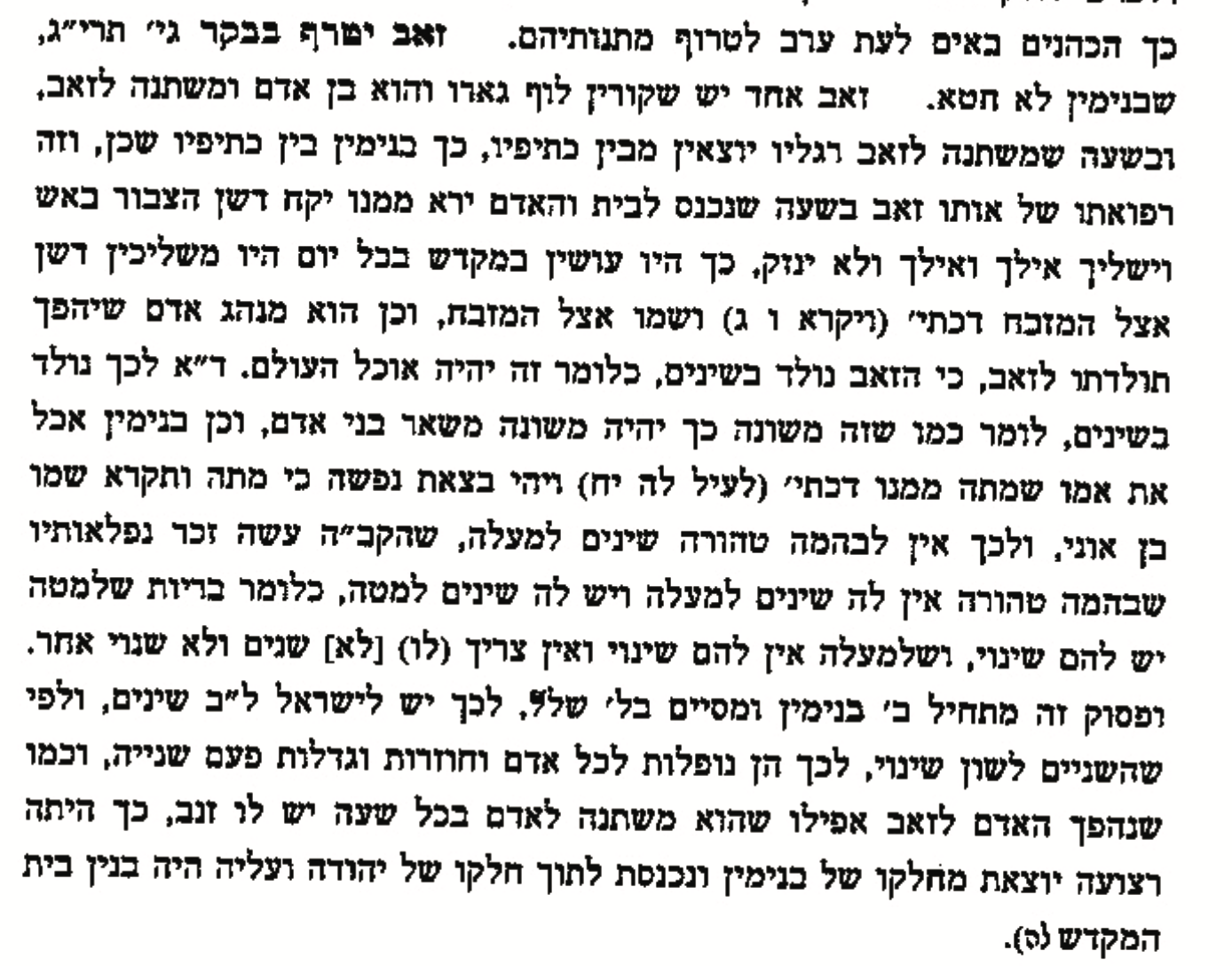

A thirteenth century Hebrew Midwifery Manual

Klalei haMilah (The Rules of Circumcision), is a work attributed to Jacob haGozer and Gershom haGozer, a father and son team who were both known by their profession (haGozer, lit. ‘the cutter’). They practised in Worms during the first half of the thirteenth century, and one chapter of their guidebook addresses midwifery, based on (of all things) the first chapter of the biblical book of Ezekiel. Here is a flavor, from a 2019 paper on the topic by Elisheva Baumgarten.

‘As for your birth, when you were born’ (Ezekiel 16: 4) – Thus we learn from this that a woman may be delivered on the Sabbath. ‘Your navel cord was not cut’ – Thus the umbilical cord is severed for the newborn (lit. child) on the Sabbath and it is tied on the Sabbath because its life depends on it. “You were not bathed in water to smooth you” – Thus the infant is washed in order to smooth its skin. “You were not rubbed with salt,” – Thus the infant is salted on the Sabbath.

And R. Gershom the Circumciser, of blessed memory, explained that when he questioned the midwives (about this practice), they said that they do not salt the child at all; God forbid, for how could he tolerate any salt? However, they salt the placenta, and they also pour wine on it, and [moreover], she [one of the midwives] says that it (wine) is good for the mother of the child for it will season her food. ‘Nor were you swaddled’—Thus, the infant is swaddled on the Sabbath. ‘Swaddled’: meaning they bind the child in cloth rags that fix him and straighten his limbs. As we have said here (lit. now), Everything that is enumerated in the Chapter of Rebuke may be done for women in labour on the Sabbath. Thus, the infant would be endangered if we did not carry out all that is mentioned in this chapter; therefore, these (actions) are permitted on the Sabbath without sin (lit. even when premeditated).

Jewish Midwives in Eighteenth Century Germany

In a fascinating paper published in 2022, the Israeli academic Nimrod Zinger noted that the names and actions of several midwives appear in the memorial books of German Jewish communities, known as memorbikher. “The criterion for entering the memorbukh was a donation to one of the community’s institutions, made by family members of the deceased or by the deceased themselves,” and their names were read by the cantor each Shabbat. Here is an example, from the Pinkas hazkharat neshamot be-kehilat Wermaiza (Jerusalem, National Library of Israel, MS Heb. 656–4), 45:

May God remember the soul of old Mrs. Hech’le daughter of Rabi Toviya z”l with the souls of S.R.R.A. [Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah], for she rose early in the mornings and went in the evenings to the synagogue. For her lovingkindness [gemilut ḥasadim] toward the poor and the rich, and for delivering babies for several years for free, in our community and in other places. Her heirs gave, on her behalf, some golden coins for charity. our community and in other places. Her heirs gave, on her behalf, some golden coins for charity. our community and in other places.

We should note that Hech’le did not receive payment for her services, but instead practiced midwifery as part of her charitable activity. And here is another mention, this time from the community of Vienna:

May God remember the soul of the pious Mrs. Mara’le daughter of R. Natan Segal z”l…for she was charitable for every person near and far, and did charity for poor and far [rich], and was modest in all her actions, and for the women in labor among our people she did as Shifra and Puah and was a woman of valor.

Zinger noted that these descriptions demonstrated that “patients often chose not to call on physicians or professional healers, such as doctors or surgeons, but rather on non professional healers, who usually did not receive payment for their aid.” In addition to acting as midwives, many women mentioned in these German memorial books provided other charitable services, including treating wounds and fractures, and burying the dead. Consider, for example, Fromet Shnabir of Frankfurt, who died in 1724:

[She was like] Shifra and Puah and sat nights and days by women in labor and the sick, poor and rich, and dealt with medications and bandages by herself …with the living and the dead…with any person in issues of medications, bruises and wounds for the rich and the poor, and any person who turned to her, and she lent [money] to the poor in times of need.

Sometimes, the midwife was part of a healing duet, in which her husband was a physician. Here is a description of Rachel the midwife and her husband of Zelcely the physician, who lived in Mainz.

the important, decent, and pleasant woman… Mrs. Rachel Frumrechi, daughter of the deceased Rabbi Meir Katz, wife of the deceased Rabbi Zelcely the rofeh [physician]…who went all her days in the path of the righteous, who did charity with her body and with her money for the poor and for the rich. She did good deeds, visited the sick, and always went to the women giving birth to save them.

Still, even pious midwives needed an income, which is why a contract was sometimes drawn up in which there was a guarantee of payment for the services of a midwife. Here is one that was signed in July 1759 in Offenbach, between the Jewish community and a midwife named Haya’le:

Her annual salary of twenty-five gold coins will be paid by the community, may God protect it, in four payments [i.e., every three months]. It was also promised that she will be provided free accommodation according to her need. There is also a need to settle her status before His Majesty. Anyone who calls for her to perform a delivery will have to pay her at least one gold coin, and every householder whose wife is about to deliver must call for her, and if he does not, he will have to pay the mentioned gold coin before his wife leaves her bed. The community, may God protect it, will be pledged for that gold coin, with the agreement of the householders. She has to notify the officer on duty [parnas ha-hodesh] if she does not receive her fee before the wife leaves her bed. Then the community may prevent the husband from conducting smechim bezetam [the ritual surrounding a woman’s arrival at the synagogue after her son’s birth] if he does not pay before the Sabbath.

(According to Zinger, this turned out not to be enough, and in 1761 Haya’le asked for an increase. The community agreed to raise to sixty gold coins, and to provide her with firewood for winter.)

“Elka Godel, born in Mea Shearim (a Jerusalem neighbourhood), went to Vienna for her training and returned home with her diploma in 1901. However, her young age was to her disadvantage. She was sent by the Jewish Colonisation Association to Zichron Ya’akov (a settlement near Haifa) as a replacement for the local midwife. Since she was only 22 years old, not yet married and had not given birth herself, she was greeted by the local population with a lack of trust, until she finally managed to attend a number of successful births”

Polish midwife certificate awarded to Sara Malia Goldfarb (nee Arzt). Sara was born in Jaroslaw (then part of the Austrian Empire, and graduated from the Royal Imperial School for Midwives in Lwow (now Lviv in Ukraine) on 15 July 1882. She practised as a midwife in Port Said, Egypt. Sara Malia and some of her siblings had gone to Egypt for the opening of the Suez Canal several years earlier, in 1869. Image courtesy of Albert Braunstein, Sara’s great-grandson and Talmudology reader.

Jewish Midwives in Late Ottoman Palestine

In her 2010 paper, Zipora Shehory-Rubin noted that the first midwives in Eretz Israel had no formal professional education and were therefore generally ignorant of hygienic necessities. In late Ottoman Palestine, poor living conditions, overcrowding and lack of minimal sanitary and hygienic conditions led to high rates of both maternal and infant mortality.

The great majority of the country’s inhabitants lacked any kind of medical help or treatment, making do with all sorts of herbal remedies, whispered prayers, supposed healing powers and amulets, and even asking help of what one might call witch-doctors… the causes of the high incidence of illness and death among infants… included unhygienic living conditions with crowding, lack of lighting and fresh air, the flow of raw sewage, accompanied by filth and foul odours. There was a lack of public services for the removal of sewage and garbage. Water was collected in cisterns, and was insufficient in quantity and quality. There was also malnutrition, insufficient clothing and heating during the winter, widespread disease and epidemics, as well as the frequency of drought and famine years. Moreover, premature marriages impaired the health and longevity of young mothers and their offspring.

To address this, the Ezrat Nashim (Women’s Help) Society was founded in 1895, to care for pregnant women, and to provide a midwife for those too poor to pay for one. In 1898, there were 22 midwives in Jerusalem, of whom 13 were Ashkenazi and 9 were Sepharadi. Few had any theoretical training and some could neither read nor write. Many of the midwives were older widows, who went out to work to provide income for their families. But there was little in the way of modern medicine to be practiced. Commonly, to induce labor or prevent a difficult birth, many women resorted to placing the key of the synagogue under their pillow, or taking a thread from the cover of the Ark and tying it to the bed.

If the birth ended in success, the midwife would receive her fee from the head of the family and in due course leave the house, in order to be ready for her next case. Sometimes the midwife would receive items of food (sugar, oil, bagels, raisins or dates) and small gifts (such as a kilo of soap) in addition to her fee. If a son was born, the midwife won a higher fee, and visitors and relatives used to leave her small gratuities or gifts. Before she left the house, the father would ask her to attend the next birth.

It is little wonder, therefore, that in 1925 the Annual Report of the Jerusalem Branch of the Hebrew Women’s Federation, observed that “there wasn’t a woman in the old city [in Jerusalem] or outside, who had not experienced the death of two or three babies at birth, or shortly thereafter, from among the eight to twelve children they had brought into the world.”

The Fertility Institute Named after a Biblical Midwife

In Israel today, The Institute of Fertility and Medicine According to Halacha (מכון פועה - פוריות ורפואה ע"פ ההלכה) is named Machon Pu’ah, after, of course, our very own midwife from this week’s parsha. Here is their mission statement:

Whether individuals are struggling with fertility, women's health, men's health, genetics or intimacy, PUAH is here to help. PUAH advisors embody a unique synthesis of rabbinical knowledge and specialized training in modern reproductive medicine to provide the best guidance possible. Our counseling and guidance is free-of-charge, helping to ease the difficult journey. All that we do is carried out in accordance to Jewish law, with deep sensitivity and compassion.

So this week, if you are looking for a charity to support, think of Machon Pu’ah, and send them a donation in honor of Shifra and Pu’ah and Abaye’s Mother, and Hech’le and Haya’le and Fromet and Rachel and all the unnamed and and unrecognized Jewish midwives who, over many thousands of years, were the unsung heroes of Jewish continuity.

Childbirth and care of the neonate has long been the provenance of women, starting with the Hebrew midwives Shifrah and Pu’ah. The knowledge that midwives passed down to each other saved countless babies from the complications of childbirth or the rigors immediately following it. While some of their advice was certainly in error from our modern perspective (Abaye’s nurse recommended placing a baby in a sieve and shaking her in order to get her to urinate,) their knowledge and skills often worked. Otherwise we would not be here to tell about it.

“[Frumit’le] was involved in charity work for the living and for the dead. She delivered young babies at the hekdesh [Jewish hospital] like Puah and Shiphrah...She did not neglect any mitzvah, big or small, and prepared medications with no charge for the rich and the poor alike.”