שבת עה,א

אָמַר רַבִּי שְׁמוּאֵל בַּר נַחְמָנִי אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן: מִנַּיִן שֶׁמִּצְוָה עַל הָאָדָם לְחַשֵּׁב תְּקוּפוֹת וּמַזָּלוֹת — שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וּשְׁמַרְתֶּם וַעֲשִׂיתֶם כִּי הִיא חׇכְמַתְכֶם וּבִינַתְכֶם לְעֵינֵי הָעַמִּים״, אֵיזוֹ חָכְמָה וּבִינָה שֶׁהִיא לְעֵינֵי הָעַמִּים — הֱוֵי אוֹמֵר: זֶה חִישּׁוּב תְּקוּפוֹת וּמַזָּלוֹת

And Rabbi Shmuel bar Nahmani said that Rabbi Yochanan said: From where is it derived that there is a mitzva incumbent upon a person to calculate astronomical seasons and the movement of constellations? As it was stated: “And you shall guard and perform, for it is your wisdom and understanding in the eyes of the nations”(Deuteronomy 4:6). What wisdom and understanding is there in the Torah that is in the eyes of the nations, i.e., appreciated and recognized by all? It is the calculation of astronomical seasons and the movement of constellations, as the calculation of experts is witnessed by all.

According to the great Rabbi Yochanan (or more likely Rabbi Yonatan, since he was Rabbi Shmuel’s teacher) it is a mitzvah for every person to calculate for herself the positions of the planets and constellations. This is also the position of the important work Sefer Mitzvot Gagdol (#47) complied by Moses ben Jacob of Coucy and completed in 1247. Moses gave two reasons for this mitzvah. The first is that by understanding astronomy, farmers will gain insight into the planting cycle. And secondly, a knowledge of astronomy and the passage of the seasons will help determine when additional months must be intercalated into the calendar so as to allow Pesach to be celebrated in the Spring. But Rabbi Yochanan’s prooftext “for it is your wisdom and understanding in the eyes of the nations” suggests that it is not just about an understanding of astronomy. That knowledge must be demonstrated to those outside of Judaism. And there is, in fact, a long tradition of Jews being astronomers, and sharing their knowledge far beyond the Jewish community. It started with the very first Jew: Abraham.

THE THREE Abraham the Astronomers

According to David Gans, Abraham, the first Jew, was also the first Jewish astronomer. Gans, who wrote his compendium on astronomy around 1612, believed that Abraham had obtained his own knowledge of the stars from none other than the primordial human, Adam.

Adam was an outstanding astronomer . . . and Josephus has written that when Abraham went down to Egypt because of the famine he taught them astronomy and mathematics and was praised by the Egyptians for his outstanding wisdom in these two disciplines....Abraham passed this knowledge to his son Isaac and grandson Jacob.

And so began our long tradition of taking a special interest in astronomy. It would be hard to call the early medieval practitioners astronomers in the modern sense of the word, since almost none actually sat around and looked at the motions of the heavens. Instead they translated works of astronomy into Hebrew, or drew up tables and charts of where the planets could be located, called ephemerides. One of the earliest was Sahl ibn Bishr al-Israili (c. 786–c. 845), also known as Haya al-Yahudi (Haya the Jew) who is believed to have been the first person to translate Ptolemy’s Almagest into Arabic, though not everyone believes that he was actually Jewish.

There is no doubt though that the famous exegete, grammarian and poet Abraham ibn Ezra (d.1167) was Jewish. And he was also a bit of an astronomer too. Actually what he did was mostly astrology, but hey, that’s what everyone did in the twelfth century. He was, according to Bernard Goldstein, “one of the foremost transmitters of Arabic scientific knowledge to the West,” and since Ibn Ezra was one of the first scholars to write on scientific subjects in Hebrew, he had to invent or adapt many Hebrew terms to represent the technical terminology of Arabic. Sadly, some of his translations and original works are no longer extant, but among his most famous works are Sefer Ha’Ibbur (The Book of Intercalation), about the calendar, and Sefer HaMeorot, on medical astrology.

A third “Abraham the Astronomer” was the Spanish Abraham bar Hiyya (d. 1136) who was also an important mathematician. This Abraham wrote Tzurat Ha’aretz (The Form of the Earth) on the formation of the heavens and the earth, as well as Cheshbon Mahalach HaKochavim (Calculation of the Course of the Stars).

Levi ben Gershon

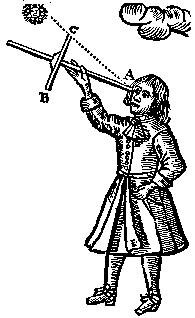

Measuring the height of a star with a Jacob's Staff. From John Sellers' Practical Navigation (1672).

Levi ben Gershon (d.1344) -the “Ralbag” - lived a century later and made an enormous contribution to astronomy. He is well known as a Jewish philosopher and the author of Sefer Milhamot Ha-Shem, (The Wars of the Lord), which took some twelve years to write. He also wrote Ma’aseh Choshev, a work on mathematics. It was not widely read outside of Jewish circles since it was never translated from the Hebrew, though it contains a number of very important theorems. But Levi was also an astronomer in the sense of the word used today. According to the late Yuval Ne’eman, “he personally remeasured everything, basing his models on his own observations only. In that, he is rather unique for that period. Levi writes "no argument can nullify the reality that is perceived by the senses, for true opinion must follow reality, but reality need not conform to opinion" - certainly not the usual position in the Middle Ages.” The Ralbag is also generally credited with the invention of an astronomical device called Jacob’s Staff. It measured the angles between heavenly bodies, and was also used by European sailors for navigation. Levi’s contributions to astronomy are recognized today; there is a crater on the moon named after him.

David Gans, Astronomer Extraordinaire

Another Jewish astronomer who actually did real astronomy was David Gans, who we mentioned above. Gans was born in 1541 in Germany though he spent most of his later life in Prague. While there, he frequented the observatory of Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler and learned his astronomy directly from what he saw. His description of the time he spent inside the observatory is perhaps the only one of its kind in rabbinic literature: It’s worth reading just for that:

I can recount how in the year 5360 (1600) our exalted lord Emperor Rudolf (may his glory be uplifted), a man of wisdom, full of general knowledge and expert in astronomy, who values and honors those who are learned, sent a mission to Denmark to invite the eminent scholar Tycho Brahe. He was a scientist and learned in astronomy, and a man who is a prince among his people. The Emperor installed him in a castle in Benatky (which is about five parsaot from the capital Prague), where he remained isolated. [Rudolf] gave him a yearly allowance of three thousand talars together with bread, wine and beer, not to mention other gifts. There he lived with twelve others, all of whom were experts in astrology [sic] and in the large instruments [for measuring,] the likes of which had never been seen. The Emperor Rudolf built thirteen consecutive rooms, and in each room were special instruments that enabled them to view the paths of the all the planets and most of the stars.

Throughout the year they would make and record daily observations of the Sun’s orbit, its latitude and longitude and its distance from the Earth. At night they would carefully do the same for each of the six planets and most of the stars, noting their latitude, longitude and distance from the Earth. I, your author, was there on three separate occasions, each lasting five consecutive days. I sat with them in their observatory, and I saw how they worked. They did amazing work, not just with the planets but also with the stars, recognizing each by its name. When each star would cross the meridian its position would be measured with three different instruments, each operated by two experts. This position would then immediately be transcribed into hours and minutes, for which purpose [Tycho] had an amazing clock. I can testify that none of our ancestors had ever seen or heard of such a device, and it has never been described in a book, whether written by a Jew or Gentile.

And a Famous Jewish Female Astronomer

There are dozens and dozens of other examples of famous medieval and modern astronomers that we cannot include because of space (though you can find a partial listing here). But let’s end with a Jewish astronomer who just had an observatory named in her honor - Vera Rubin (1928-2016). She was born to Jewish immigrants in Philadelphia, educated at Vassar, Cornell and Georgetown, and moved to the Carnegie Institution in Washington in the 1960s. She studied the rotation of galaxies, and discovered that something other than their matter must be holding them together. As her obituary in The New York Times noted, “her work helped usher in a Copernican-scale change in cosmic consciousness, namely the realization that what astronomers always saw and thought was the universe is just the visible tip of a lumbering iceberg of mystery.” Being a woman in a man’s field had tremendous challenges, and called for ingenuity:

…she still had to battle for access to a 200-inch telescope on Palomar Mountain in California jointly owned by Carnegie and Caltech. When she did get there, she found that there was no women’s restroom. …Dr. Rubin taped an outline of a woman’s skirt to the image of a man on a restroom door, making it a ladies’ room.

Vera Rubin was elected to the National Academy of Sciences, and last year the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope was renamed the National Science Foundation Vera C. Rubin Observatory in recognition of her contributions to the study of dark matter and her outspoken advocacy for the equal treatment and representation of women in science. Despite her achievements she remained humble. “I’m sorry I know so little. I’m sorry we all know so little” she once said."But that’s kind of the fun, isn’t it?” Yes. It is.