In 1587, Pope Sixtus V decreed that all marriages in which the man did not have two testicles in the scrotum should be dissolved. Voltaire (1694-1778), felt the need to share some further observations on the testes and the Pope's edict, in his Philosophical Dictionary:

This word [testes] is scientific, and a little obscure, signifying small witnesses. Sixtus V... declared, by his letter of the 25th of June, 1587, to his nuncio in Spain, that he must unmarry all those who were not possessed of testicles. It seems by this order...that there were many husbands in Spain deprived of these two organs...We have beheld in France three brothers of the highest rank, one of whom possessed three, the other only one, while the third possessed no appearance of any, and yet was the most vigorous of the three.

...[The] Parliament of Paris, on the 8th of January, 1665, issued a decree, asserting the necessity of two visible testicles, without which marriage was not to be contracted.

Which brings us to today's daf, Yevamot 75a. To catch up quickly: The Mishnah (on 70a) listed the circumstances under which a Cohen is not allowed to eat terumah. Among those banned from this edible delight is a Cohen with an injury to his testicles - and this same injury, the Mishnah continues, when found among other Jewish men, may prevent that man from marrying.

In discussing the details of what kind of testicular injury results in a ban on marriage, we read the following:

אמר רבי ישמעאל בנו של ר' יוחנן בן ברוקה שמעתי מפי חכמים בכרם ביבנה כל שאין לו אלא ביצה אחת אינו אלא סריס חמה וכשר סריס חמה

Rabbi Yishmael the son of Rabbi Yochanan ben Berokah said: I heard from the sages in the vineyard at Yavneh that whoever has only one testicle [at birth] is called "sterile from the sun" [i.e. naturally sterile] and is allowed to marry...

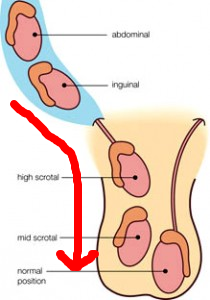

So according to this report of Rabbi Yishmael, the sages in Yavneh allowed a man born with one testicle to marry. The Talmud is describing a condition known as cryptorchidism in which one or sometimes both of the testes remains undescended and hide somewhere within the abdomen.

To understand why the testes take this hike, there's some embryology involved. Rather than explain with words, here is a stunning animation showing why the testes develop where they do and how they descend. Grab a cup of coffee and listen as Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade op. 35 plays in the background. The formation of the testes begin at 1:02 if you are in a hurry (but don't be).

Animation is derived from Keith L. Moore, T.V.N. Persaud, Mark G. Torchia, "Before We Are Born: Essentials of Embryology and Birth Defects", 8th edition. Elsevier, 2012.

If you didn't watch the video, here is what you need to know:

Got it? OK. So the testes develop in the abdominal cavity and migrate southwards into the scrotum. Usually they land there by birth, or soon after, if they behave themselves. Which they don't always do. Sometimes one of the pair (and very rarely both) fail to migrate. Sometimes they descend and then, apparently disappointed by their new cool accommodations, bolt back north to the warmth of the abdomen.

Which brings us to the question, just how common is cryptorchidism?

The best answer will be an educated guess because the data is not great. One of the few studies of the epidemiology of this condition comes from the medical examination of English schoolboys published in 1941. It reported that the incidence of cryptorchidism in 3,300 boys under 15 was almost 10%, but that this number dropped to less than 1% in boys older than 15.

And then in this paper comes this delicious line.

“Sir Robert Hutchison tells me that he knew a man in whom descent occurred while he was an undergraduate at Oxford (an event duly celebrated by a party)”

A more recent study from 2007 put the incidence of undescended testes at 1-4.6% at birth (depending on the infant birthweight), while at age 11 the incidence is anywhere from 1.6-2.2%. The incidence is higher in low birth-weight and premature boys.

What is clear is that there is an association with fertility and cryptorchidism, even when the testicle that went AWOL is retrieved and secured in the scrotum.

“The incidence of azoospermia in men with unilateral cryptorchidism is 13% regardless of the fate of the testis”

Which brings us back to the prohibition against a man with injured testes (or penis- as in Deut. 23:2: לא יבא פצוע דכא וכרות שפכה בקהל) marrying. It is related to his presumed inability to father a child. Voltaire seems to have been unsure of the role of the testes (whether one, two, or in one lucky case "three",) but Rabbi Yishmael's סריס חמה, a man with only one visible testicle, while certainly less fertile than a normal man, is capable of fathering a child. Hence his marriage, while not encouraged, is recognized, and this is codified as normative Jewish law.

סריס שקדש, בין סריס חמה בין סריס אדם, וכן אילונית שנתקדשה, הוי קדושין

(שולחן ערוך אבן העזר הלכות קידושין סימן מד, ד)

If a man with one testicle married, whether this condition is from birth or later acquired, he is legally married.

Today, an undescended testicle is surgically brought into the scrotum at an early age, so that the cryptorchidism described by Rabbi Yishmael has been virtually eliminated, as have been some very interesting parties at the University of Oxford.