On tomorrow’s page of Talmud, we will read the following:

כתובות י, ב

הַהוּא דַּאֲתָא לְקַמֵּיהּ דְּרַבָּן גַּמְלִיאֵל בַּר רַבִּי אֲמַר לֵיהּ רַבִּי בָּעַלְתִּי וְלֹא מָצָאתִי דָּם אֲמַרָה לֵיהּ רַבִּי עֲדַיִין בְּתוּלָה אֲנִי

אָמַר לָהֶן הָבִיאוּ לִי שְׁתֵּי שְׁפָחוֹת אַחַת בְּתוּלָה וְאַחַת בְּעוּלָה הֵבִיאוּ לוֹ וְהוֹשִׁיבָן עַל פִּי חָבִית שֶׁל יַיִן בְּעוּלָה רֵיחָהּ נוֹדֵף בְּתוּלָה אֵין רֵיחָהּ נוֹדֵף אַף זוֹ הוֹשִׁיבָה וְלֹא הָיָה רֵיחָהּ נוֹדֵף אָמַר לוֹ לֵךְ זְכֵה בְּמִקָּחֶךָ

The Gemara relates: A certain man who came before Rabban Gamliel bar Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi said to him: My teacher, I engaged in intercourse and did not find blood. The bride said to him: My teacher, I am still a virgin.

Rabban Gamliel said to them: Bring me two maidservants, one a virgin and one a non-virgin, to conduct a trial. They brought him the two maidservants, and he seated them on the opening of a barrel of wine. From the non-virgin, he discovered that the scent of the wine in the barrel diffuses from her mouth; from the virgin he discovered that the scent does not diffuse from her mouth. Then, he also seated that bride on the barrel, and the scent of the wine did not diffuse from her mouth. Rabban Gamliel said to the groom: Go take possession of your acquisition, as she is a virgin.

And so there was a happy ending to the story, and thus began the couple on a journey of happiness and mutual trust.

Another case of the Barrel TesT

In the last, bloody chapter of the Book of Judges, the civil war against the tribe of Benjamin reaches its climax. For reasons that we don’t have time to get into, four hundred virgins were captured from the town of Yavesh Gilad, and offered as a peace offering to the men of Benjamin.

21:12 שופטים

וַֽיִּמְצְא֞וּ מִיּוֹשְׁבֵ֣י ׀ יָבֵ֣ישׁ גִּלְעָ֗ד אַרְבַּ֤ע מֵאוֹת֙ נַעֲרָ֣ה בְתוּלָ֔ה אֲשֶׁ֧ר לֹא־יָדְעָ֛ה אִ֖ישׁ לְמִשְׁכַּ֣ב זָכָ֑ר וַיָּבִ֨אוּ אוֹתָ֤ם אֶל־הַֽמַּחֲנֶה֙ שִׁלֹ֔ה אֲשֶׁ֖ר בְּאֶ֥רֶץ כְּנָֽעַן׃

They found among the inhabitants of Jabesh-gilead 400 maidens who had not known a man carnally; and they brought them to the camp at Shiloh, which is in the land of Canaan

How, wondered the rabbis on that page of Talmud, did the soldiers know who was, and who was not, a virgin? Easy, said Rav Kahana, who lived in Babylon around the year 250 CE. All you need is a barrel of wine and a good sense of smell.

יבמות ס, ב

מְנָא יָדְעִי? אָמַר רַב כָּהֲנָא: הוֹשִׁיבוּם עַל פִּי חָבִית שֶׁל יַיִן, בְּעוּלָה — רֵיחָהּ נוֹדֵף, בְּתוּלָה — אֵין רֵיחָהּ נוֹדֵף

How did they know that they were virgins? Rav Kahana said: They sat them on the opening of a barrel of wine. If she was a non-virgin, her breath would smell like wine; if she was a virgin, her breath did not smell like wine.

(Rav Kahana, by the way, demonstrated an unusual enthusiasm when it came to the study of sexuality. It was he who hid under the bed of his teacher Rav, while the latter was having intercourse with his (Rav’s) wife. When Rav discovered this intrusion and asked for an explanation, Rav Kahana famously replied “תּוֹרָה הִיא, וְלִלְמוֹד אֲנִי צָרִיךְ” - “this too is Torah, so I need to learn all about it.” Rav’s outrage is not recorded.)

Maybe it’s all a metaphor

Perhaps this passage of Talmud should be understood as a metaphor. Here, for example is the commentary of Rabbi Shmuel Eidels, better known as the Maharsha (1555 – 1631):

מהרש"א חידושי אגדות מסכת יבמות דף ס עמוד ב

הכתוב שהוא מורה על הזנות ועבירה דבתולות כמ"ש זנות ויין וגו' ותירוש ינובב בתולות וק"ל

The verse teaches a relationship between immorality and virginity, as it is written “harlotry and wine [and new wine take away from the heart]" (Hos. 4:11) and "new wine will cause maids to speak" (Zec. 9:16), which is easy to understand.

Except that the passage in Ketuvot is clearly describing something that Rabban Gamliel actually did, and Rav Kahana in Yevamot was not suggesting a metaphor. So today on Talmudology, we ask what you were all thinking. “Is there anything to the suggestion that this test really works?”

©ufabizphoto - Can Stock Photo Inc.

Bertrand RusselL’s Teapot

The great British philosopher Bertrand Russell (d.1970,) was also a great British atheist, who tired of some of the claims made in support of a belief in God. In 1952 he wrote the following:

Many orthodox people speak as though it were the business of sceptics to disprove received dogmas rather than of dogmatists to prove them. This is, of course, a mistake. If I were to suggest that between the Earth and Mars there is a china teapot revolving about the sun in an elliptical orbit, nobody would be able to disprove my assertion provided I were careful to add that the teapot is too small to be revealed even by our most powerful telescopes. But if I were to go on to say that, since my assertion cannot be disproved, it is intolerable presumption on the part of human reason to doubt it, I should rightly be thought to be talking nonsense. If, however, the existence of such a teapot were affirmed in ancient books, taught as the sacred truth every Sunday, and instilled into the minds of children at school, hesitation to believe in its existence would become a mark of eccentricity and entitle the doubter to the attentions of the psychiatrist in an enlightened age or of the Inquisitor in an earlier time.

Whether or not one believes that Russel’s teapot is a reasonable analog to theistic belief, it is a reminder that when making an empirically unfalsifiable claim, the burden of proof does not lie on others to disprove it. We have no reason to believe the claim unless it has been proven by those who asserted its truth. It is worth remembering Russel’s teapot when considering some claims made in the Talmud; those which are not plausible must be considered to be just that, regardless of whether the claim has been empirically disproven.

Rather unexpectedly, one noted scholar seems to have taken up Russel’s Teapot challenge, and set out to explain that the Barrel Test as described by Rabban Gamliel, was a reliable test of a woman’s virginity.

Rabbi Mordechai Halperin AND The Barrel TesT

Rabbi Mordechai Halperin is an accomplished and highly respected physician in Jerusalem. Some of his books adorn the Talmudology library. He was the Chief Ethics officer at the Israeli Ministry of Health, and the editor of Assiah, the Journal of Jewish Ethics and Halacha. And Rabbi Halperin believes that the test has a basis in fact. Here are the steps in his argument, (and you can read the original here):

1) Some foods, like garlic, are broken down into substances that are absorbed into the bloodstream. These may later be expelled from the blood in the lungs, and may be smelled on the breath.

2) Many medicines and food substances can be directly absorbed from the mucosa. So, for example, some drugs are placed under the tongue, where they may directly enter the blood stream by crossing into the tiny blood vessels that line the mucosal surface. Alcohol can not only be absorbed into the blood by ingestion into the stomach. It may also cross directly, via a mucosal surface. The vagina is a mucosal surface,

3) The difference between a virgin and non-virgin is in the tone of the vaginal passage.

As a result, Rabbi Halperin claims that a non-virgin has a lower vaginal tone and that the vaginal mucosa will absorb more alcohol when placed over a wine barrel when compared with a woman who is a virgin. And so the blood alcohol concentration will be higher in the former than in the latter. This will be detectable by the smelling the breath of the woman. QED.

Before we go on, an apology

OK, before we go on any further, I want to apologize to the many woman (and men) who might feel outraged at this discussion. I know it reminds us of a time when, in Judaism (and in Christianity too) virginity was the most important of qualities that a bride could have. (For more on that, see yesterday’s post.) In many cultures it still is, and women who are suspected of not being virgins on the night of their wedding sometimes face violence and even murder. Here is Michael Rosenberg’s take, from his terrific (and expensive) book Signs of Virginity: Testing Virgins and Making Men in Late Antiquity (p.139):

We need not - and should not - ignore the grotesque and degrading image of setting a woman up on a barrel to test her virginity to see that Rabban Gamliel b. Rabbi’s action is meant to bear the trappings of an objective process….

Critical to understanding the story is reading it in the light of its parallel in Tractate Yevamot of the Bavli. There, the Babylonian sage Rav Kahana suggests the barrel method for determining virginity. The striking difference between the appearance of the barrel test in bYev60b and its appearance here is that the version in Yevamot lacks the use of two maidservants to test out the method. There, Rav Kahana simply explains what one should do. In our passage [in Ketuvot] , this plot device highlights the “objectivity” of what Rabban Gamliel b. Rabbi is doing; the editor(s) of the story depict Rabban Gamliel b. Rabbi’s experiment as rigorous and /or objective. In the language of the modern scientific method: he tests out a hypothesis using controlled variables, and when that hypothesis is confirmed, he then makes use of it to determine the answer to an unknown question.

So, we must continue, in the name of science. The problem with Rabbi Halperin’s suggestion is that while the individual steps might be correct, they do not in any way lead to his conclusion.

How Scientific was Rabban Gamliel’s Methodology?

Rosenberg points out some of the features that Rabban Gamliel’s test has in common with “the language of the modern scientific method.” But to be clear, there was nothing scientific about it, at least in so far as we use the word today. For this, Rabban Gamliel cannot be blamed. He lived about 1,300 years before the birth of modern science, and it is silly of us to think he should have been conducting his test along the same lines that we conduct scientific tests today. Still, it is worth thinking about his methods through the lens of modern science. We will quickly see that the test, at least as described in Ketuvot, was far from scientific.

Rabban Gamliel selected two women to take part in the calibration phase. They were “maidservants” a position that might mean anything from an employee to a slave. Were they coerced, or did they volunteer? If the former, the study was unethical.

What were their ages, had they borne the same number of children, and where in their menstrual cycles were they? The latter is especially important since it affects the lining of the vagina and uterus (more on this below).

Was the test blinded? Were the barrels identical? Was the same wine used in each? When calibrating his nose, how often did he smell? How long did each woman sit over the wine?

In the actual test, did the bride seat herself for the same length of time as the women in the calibration phase? Was the same barrel used? Was it the same wine? Was the woman in the same part of her menstrual cycle as the women in the calibration phase?

Unless we know the answers to these questions (and many more), Rabban Gamliel’s test, interesting as it is, remains a far cry from anything that would pass as modern science. While it was published in the Talmud, it would not make it into any peer reviewed journal today. (Well, OK, maybe this one.)

With the possible exception of Rabbi Shimon ben Chalafta, the rabbis of the Talmud weren’t scientists. They were rabbis.

How good is the nose at detecting blood alcohol Levels?

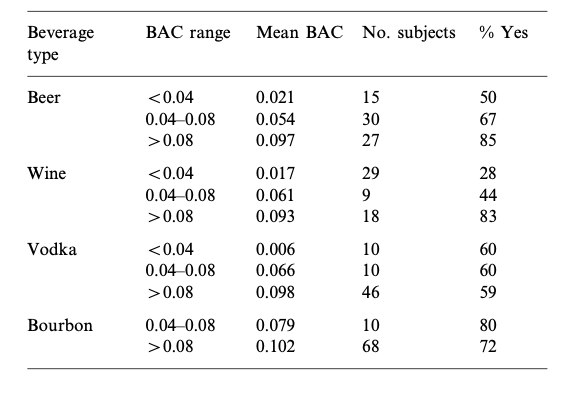

Most of us are able to smell alcohol on the breath of a person who has consumed it. (Yes, I know that actually, pure alcohol has very little or no odor [think of vodka] and that the smell is really from the tannins, hops and other substances that make up the wine or beer or whatever. But let’s keep going.) How sensitive are our noses? Not very, it turns out. In one study, twenty “experienced” police officers were asked to smell the breath of fourteen volunteers who had been drinking, and whose precise blood alcohol concentrations (BACs) were known. How did the officers do?

Well, it depends on the BAC. Consider a BAC of 0.08%, the legal limit for driving in many places. To get that, most people would need to have four or five drinks. At that high level, the odor was correctly identified 80% of the time. At levels less that that, the alcohol could not usually be detected.

Decisions for positive BACs by beverage type and BAC. From H. Moskowitz et al. Police officers’ detection of breath odors from alcohol ingestion. Accident Analysis and Prevention 1999. 31; 175–180.

It should be noted that wine was the hardest odor to detect, and that when BACs were lower than 0.04% fewer than one third of noses could smell alcohol.

It might be countered that Talmudic wines were far stronger than wine made today; in fact, Rabbi Yosef Chaim of Baghdad, better known as the Ben Ish Chai, makes just this claim in his commentary on Yevamot.

ומה שהיה מסתפק רבן גמליאל בתחלה בניסיון זה היינו משום דחשש אולי יין של דורות ראשונים בזמן שעשו לבנות יבש גלעד היה יותר חזק מן יינות שבימיו ולכך אותו יין בדק וזה אינו בודק על כן עשה ניסיון תחלה בשפחות

Rabban Gamliel was initially uncertain about the test because of the concern that the wine that was used earlier in history , when it was used to test the women of Yavesh Gilad, was stronger that the wines of his time. Perhaps, therefore, that earlier wine worked in this test, but the current wines were untested. That is why Rabban Gamliel started with the experiment with the maidservants…

These wines contained a greater alcohol content, and so would cause a greater spike in the blood alcohol level. This may have been so, but there is good evidence (like this) that water was added to wine because that was the way the Greeks drank it, not because it was otherwise too strong to imbibe.

The Vaginal Mucosa and drug absorption

I am not aware of any research describing how a woman’s blood alcohol content varies with time she spent over a barrel of wine. But there is a lot of work on the vagina and its role in drug absorption. One review of the topic from two pharmacologists at Texas Tech noted that the“successful delivery of drugs through the vagina remains a challenge, primarily due to the poor absorption across the vaginal epithelium.” If that is true for drugs directly introduced into the vagina, the vaginal absorption of alcohol over a barrel must be considerably worse, if it exits at all.

To counter this factor, there is the urban legend of women inserting vodka filled tampons into their vaginas to get drunk. Snopes, which concluded the rumor was false did add this, though:

If one were to ingest vodka vaginally (or anally, as the rumor is also expressed that way), the practice wouldn’t result in booze-free breath because alcohol is partially expelled from the body via the lungs. Once liquor is in the blood, at least some of it gets breathed out, which is how breathalyzers measure blood alcohol content.

They provided no reference for this claim, though I suppose they could have cited Yevamot 60b. Be that as it may, the amount of alcohol absorbed by the vaginal mucosa would be so negligible as to be unmeasurable, and certainly not detectable on the breath.

Ancient Greeks and the Barrel Test

In his Hebrew defense of the barrel test, Rabbi Dr. Halperin did not place the belief into a context. And context is always important when examining the Talmud, because it was, after all, a product of its time and place (even if that time spanned several hundred years, the the place spanned many hundreds of miles). It turns out that the belief in smells and fragrances easily passing in and out of a woman’s body was also one that was held by the Ancient Greeks. Writing at least six hundred years before Rabban Gamliel bar Rabbi (who was a first generation Amora, and lived around the third century C.E) or Rav Kahana, the Greek physician Hippocrates had this to say:

If a woman does not conceive, and wish to ascertain whether she can conceive, having wrapped her up in blankets, fumigate below, and if it appears that the scent passes through the body to the nostrils and mouth, know that of herself she is not unfruitful.

The uterus, it was once believed, had a sort of mind of its own, and was especially partial to strong smells. Here, for example, is Aretaeus of Cappadocia, who lived around the time of Galen in the second century CE, perhaps only two or three generations before Rabban Gamliel Bar Rabbi:

In the middle of the flanks of women lies the womb, a female viscus, closely resembling an animal; for it is moved of itself hither and thither in the flanks, also upwards in a direct line to below the cartilage of the thorax, and also obliquely to the right or to the left, either to the liver or the spleen, and it likewise is subject to prolapsus downwards, and in a word, it is altogether erratic. It delights also in fragrant smells, and advances towards them; and it has an aversion to fetid smells, and flees from them; and, on the whole, the womb is like an animal within an animal.

Still, even among the Greeks, the assumption that the uterus could absorb smells was not accepted by all. The second century physician Soranus thought the idea was mistaken, but his objections demonstrate that the idea was popular.

The fumigation of women to determine their fecundity was not only a Talmudic belief. It was apparently one that was part of the ancient world. So why would the rabbis not believe it? Has Rabbi Dr. Halperin succeeded in persuading you that Rabban Gamliel’s test could reliably work? Or have the objections we have raised left you skeptical? I will leave that for you to discuss around your shabbat table this evening.