כתובות קה ב

ת"ר "ושוחד לא תקח" אינו צריך לומר שוחד ממון אלא אפילו שוחד דברים נמי אסור מדלא כתיב "בצע לא תקח". היכי דמי שוחד דברים? כי הא דשמואל הוה עבר במברא אתא ההוא גברא יהיב ליה ידיה אמר ליה "מאי עבידתיך?" אמר ליה "דינא אית לי" א"ל פסילנא לך לדינא

The rabbis taught in a Baraisa: "You shall not take a bribe" (Exodus 23:8) It is obvious that this forbids not only a monetary bribe, but even bribery through words, since it did not write "You shall not take money." What is to be understood by ‘a bribe of words’? Like that given to Shmuel when he was crossing a bridge. A man came up and offered Shmuel his hand. "What" [Shmuel] asked him, ‘are you doing here?" He replied "I have a lawsuit [to be tried in your court]." Shmuel said to him ["now that you offered me help over the bridge] I am disqualified from judging your case." (Ketuvot 105b.)

Judicial Corruption Around the World

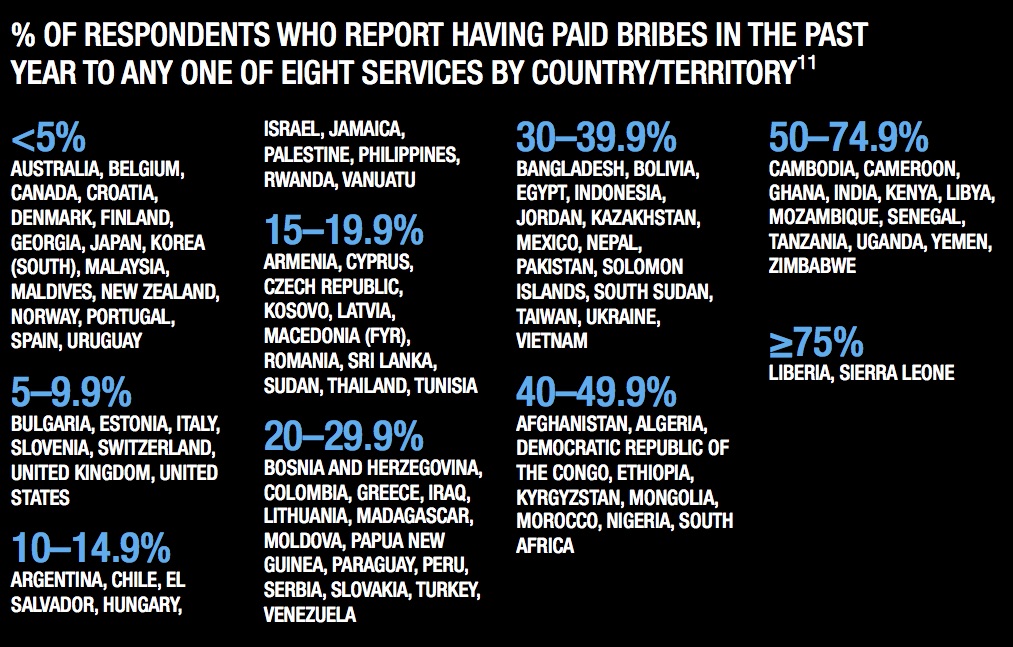

A 2013 report on global corruption in 107 countries reported that more than one in four people had paid a bribe in the last twelve months "when interacting with key public institutions and services." And among the eight services that they evaluated, "the police and the judiciary are seen as the two most bribery- prone. An estimated 31 per cent of people who came into contact with the police report having paid a bribe. For those interacting with the judiciary, the share is 24 per cent." Sadly, Israel as a whole was among the most corrupt of the OECD nations, but, on a brighter side, its judiciary received one of the highest rankings.

From The Global Corruption Barometer 2013. Transparency International.

In his 1985 paper on the moral and legal history of bribery, John Noonan suggested that in the ancient Near East, the concept of a bribe "did not exist". However, "if one wanted to meet a powerful stranger without a hostile reaction, one was required to bring an offering...One came with something to give. One expected something in return.." This pattern was only broken with the Hebrew Bible. " A very powerful force was necessary to break the ordinary relationship of reciprocity. That powerful force is the example of God."

“Nowhere in the Hebrew Bible is there an example of anyone being caught, tried and punished for taking bribes. Moreover, no one’s material interests are enlisted in the effort to prevent bribery. No class of persons has an interest in preventing bribery, detecting it, or even avoiding it. The idea of the bribe is presented as bad, God is given as an example, there is divine example and instruction, but the idea is at such a level of abstraction that one suspects that the anti- bribery rule could not have often been observed.”

Judicial Corruption in the US

While the notion that bribery of the judiciary is wrong is as old as the Bible, the earliest known example in the English literature of a judge being tried and convicted of bribery did not occur until the trial of Francis Bacon in 1621. Bacon, who served as the Lord High Chancellor, was convicted of making between 12,000 and 15,000 pounds a year in bribes - in an age when the average income was 30 pounds a year). Here in the US, Section 201 of Title 18 prohibits a direct or indirect action to offer, promise, or give anything of value to any public official or witness. Likewise, the solicitation of anything of value by a public official or witness is prohibited. Although is it less common than in, say Liberia, judges in the US have been known to take bribes. For example, in the 1980s the FBI launched Operation Greylord to investigate corruption of the judiciary in Cook County Illinois. The operation, which ran for over three years, resulted in the conviction of 15 out of the 17 judges who were tried on a series of bribery charges. More recently, State District Judge Abel Limas of Texas was sentenced to 6 years in federal prison for offenses that included accepting "money and other consideration from attorneys in civil cases pending in his court in return for favorable pre-trial rulings in certain cases." (Limas awarded $14 million in a compensation case...and later received a check for $85,000 from a law firm that represented a litigant. Bacon would have been proud.)

From The Global Corruption Barometer 2013. Transparency International.

The $3 Million Gift and the Fourteenth Amendment

A recent case about the limits of judges accepting money from litigants reached the US Supreme Court, and stands in sharp contrast to the rules we learn about in todays daf in Ketuvot. (Fun fact about this: it was used as the plot for John Grisham's best-selling legal thriller, The Appeal.) In West Virginia, Hugh Caperton sued the Massey Coal Company for fraud over a business deal, and was awarded $50 million in damages. The Coal Company appealed the verdict to the West Virginia Supreme Court. Sitting on that court was Justice Brent Benjamin, to whom the CEO of Massey Coal Company had donated $3 million for his election campaign. (For those of you who live outside of the US, here's an explanation of this extraordinary phenomenon. In almost forty states, judges - including Supreme Court judges - are not appointed. Instead, they are elected, just like politicians. And like politicians, they have election campaigns to which contributions are needed. Now back to our story.)

Now you and I would think that having donated $3 million to a judge's election campaign would would be a pretty powerful conflict of interest, but the Justice did not share our belief. Justice Benjamin denied a request that he recuse himself, and in 2007 he was part of a 3-2 decision which - shocker - found for Massey and ordered the case dismissed.

The case was then appealed to the US Supreme Court, which ruled in June 2009. In a 5-4 decision, the court found that Justice Benjamin should have indeed reduced himself from hearing the case, and that his not doing so violated the constitutional right to due process under the Fourteenth Amendment ("...nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law"). In his short dissenting opinion, Justice Scalia cited the Mishnah in Avot, and opined that the Court's decision would "create vast uncertainty with respect to a point of law that can be raised in all litigated cases in (at least) those 39 States that elect their judges."

“A Talmudic maxim instructs with respect to the Scripture: “Turn it over, and turn it over, for all is therein.” The Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Aboth, Ch. V, Mishnah 22. Divinely inspired text may contain the answers to all earthly questions, but the Due Process Clause most assuredly does not. The Court today continues its quixotic quest to right all wrongs and repair all imperfections through the Constitution. Alas, the quest cannot succeed...”

In response to Scalia's citing of Avot, an alert blogger thought a better citation would have been today's daf in Ketuvot:

Given the context of the case, I recommend to Justice Scalia the following Talmudic passage ... from the Ketubot 105 (which records many such stories), where the Talmud relates that bribes can come in the form of cash as well “in words.” In inquiring what constitutes a “bribe in words”, the Talmud reports: Like the case of when [the Talmudic sage] Samuel was crossing a bridge. A certain man approached him and gave Samuel his hand for support while crossing Samuel asked him: “What is your business?” He replied: “I have a suit in your court.” Samuel said: “I am disqualified from serving as the judge in your case”... In any event, if Scalia is going to cite Talmudic law in a case concerning judicial impartiality, he should at the very least inform us that the result he favors lies in sharp contrast to Talmudic conceptions of judicial ethics...

The Massey Case in Light of the Talmud

Writing in the Touro Law Review, Jacob Weinstein analyzed the Massey case in light of today's page of Talmud. He observed that in the Talmud, when there is a prior relationship of gift giving or favors between a litigant and the judge, the latter is automatically invalid to judge the case; no motion for recusal is necessary.

“[In American law,] a judge has broad discretion to recuse himself, as the guidelines are vague at...Jewish law, however, requires the recusal by the judge even under circumstances that appear inconsequential. Furthermore, Jewish law takes the next logical step from American jurisprudence, decreeing that such conduct is outright bribery and not just “bias” or “unfairness.””

The Talmud set a very high standard regarding judicial impartiality. How high? Well try this. We read today that Mar Ukva refused to hear a case because one of the litigants had covered some spittle that was on the ground in front of Mar Ukva. That was enough to threaten his impartiality. But here in the US, four out of nine Supreme Court Justices did not think that a $3 million contribution to a judge's election fund threatened his impartiality. Sometimes the truth is stranger than fiction. And sometimes truth becomes the plot for best-selling legal fiction. Either way, there's a lot of cleaning up to do.