בראשית 49:27

בִּנְיָמִין֙ זְאֵ֣ב יִטְרָ֔ף בַּבֹּ֖קֶר יֹ֣אכַל עַ֑ד וְלָעֶ֖רֶב יְחַלֵּ֥ק שָׁלָֽל׃

Binyamin is a ravenous wolf: in the morning he shall devour the prey, and at night he shall divide the spoil.

“Binyamin is a ravenous wolf.” What an intriguing description of a person. Was he always hungry? Did he like to hunt? Was he mostly grey? Ibn Ezra explained that, like a wolf, Binyamin was a strong fighter (דמהו לזאב כי גבור היה). Sforno explained that wolves hunt at dusk and dawn, when there is not much light. In the same way, the descendents of the tribe of Binyamin (King Shaul and Mordechai of the Purim Story) ruled at a period of Jewish history immediately before dawn - at the start of the Jewish monarchy (Shaul) and at dusk, the end of Jewish self rule (Mordechai).

binyamin the werewolf

But there is another explanation of this verse, given by the twelfth century French scholar Rabbeinu Ephraim ben Shimshon in his commentary on the Torah. You see, Rabbenu Ephraim explained that this verse means Binyamin was a werewolf.

Image from here.

Another explanation: Binyamin was a “predatory wolf,” sometimes preying upon people. When it was time for him to change into a wolf, as it says, “Binyamin is a predatory wolf,” as long as he was with his father, he could rely upon a physician, and in that merit he did not change into a wolf. For thus it says, “And he shall leave his father and die” (Gen. 44:22)—namely, that when he separates from his father, and turns into a wolf with travelers, whoever finds him will kill him.

Rabbeinu Ephraim has more to say about werewolves in general, and how they relate to Binyamin. This can be found in his commentary to Genesis 35:27. It turns out that Binyamin the werewolf ate his mother, the matriarch Rachel:

Image from here.

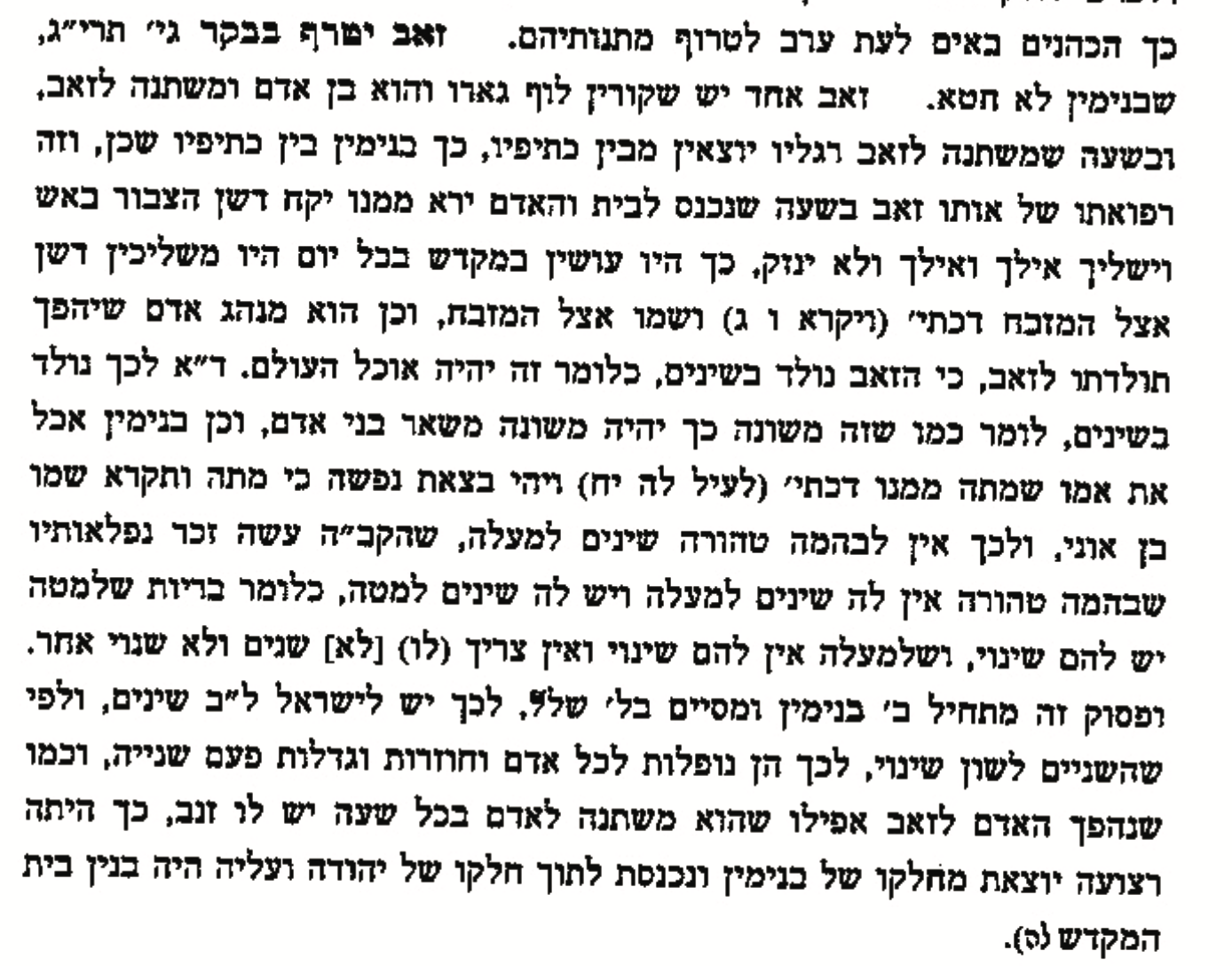

There is a type of wolf that is called loup-garou (werewolf), which is a person that changes into a wolf. When it changes into a wolf, his feet emerge from between his shoulders. So too with Binyamin - “he dwells between the shoulders” (Deuteronomy 33:12). The solution for [dealing with] this wolf is that when it enters a house, and a person is frightened by it, he should take a firebrand and thrust it around, and he will not be harmed. So they would do in the Temple; each day, they would throw the ashes by the altar, as it is written, “and you shall place it by the altar” (Leviticus 6:3); and so is the norm with this person whose offspring turn into wolves, for a werewolf is born with teeth, which indicates that it is out to consume the world. Another explanation: a werewolf is born with teeth, to show that just as this is unusual, so too he will be different from other people. And likewise, Binyamin ate his mother, who died on his accord, as it is written, “And it was as her soul left her, for she was dying, and she called his name ‘the son of my affliction’ ” (Genesis 35:18).

Rashi also believed in Werewolves

It may surprise you to learn that Rashi also believed in werewolves. Here is his commentary on Job 5:23:

איוב 5:23

כִּ֤י עִם־אַבְנֵ֣י הַשָּׂדֶ֣ה בְרִיתֶ֑ךָ וְחַיַּ֥ת הַ֝שָּׂדֶ֗ה השְׁלְמָה־לָּֽךְ׃

For you will have a pact with the rocks in the field, And the beasts of the field will be your allies.

וחית השדה. הוא שנקרא גרוש"ה בלע"ז וזו היא חית השדה ממש ובלשון משנה תורת כהנים נקראים אדני השדה

and the beasts of the field That is what is known as grouse(?) in Old French, and this is actually a beast of the field. In the language of the Mishnah in Torath Kohanim, they are called “adnei hasadeh.”

In order to translate the old French word גרוש"ה (which should be read as garove), we turn to Otzar halo’azim, a dictionary of Rashi’s old French. Under entry #4208 we read the following:

Moshe Catano, the author of this dictionary, tells us that the Rashi was using the old French word for a “man-wolf, which is refers to the legends of a man that turns into a wolf.” So yes, Rashi seems to have believed in werewolves.

On this week’s Talmudology on the Parsha, we will take a dive into the world of Werewolves. Here is the plan of what we will be discussing:

The Three Signs of Mental Illness

What is Gandrifus? Koren vs Artscroll (and Jastrow)

The Parallel Discussion in the Yerushalmi: “Man-dog”

Lycanthropy in the Ancient World

Lycanthropy and Mental Illness

Lycanthropy and Porphyria. Or Not

Lycanthropy and Melancholy

Summary

The three Signs of Mental Illness

In Chagigah, there is a fascinating discussion of what features a person must demonstrate to be declared a shoteh, or what today we might call mentally ill or insane. First, the rabbis give a description of three behaviors that might lead to this diagnosis:

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן אֵיזֶהוּ שׁוֹטֶה הַיּוֹצֵא יְחִידִי בַּלַּיְלָה וְהַלָּן בְּבֵית הַקְּבָרוֹת וְהַמְקָרֵעַ אֶת כְּסוּתוֹ אִיתְּמַר רַב הוּנָא אָמַר עַד שֶׁיְּהוּ כּוּלָּן בְּבַת אַחַת רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן אָמַר אֲפִילּוּ בְּאַחַת מֵהֶן

The Sages taught: Who is considered an insane? (1) One who goes out alone at night, (2) and one who sleeps in a cemetery, (3) and one who rends his garment. It was stated that Rav Huna said: A person does not have the halakhic status insanity until all of these signs are present at the same time. Rabbi Yochanan said: He is considered insane even due to the appearance of only one of these signs.

So far so good. This is an argument whether you need just one behavior (Rabbi Yochanan) or all three (Rav Huna). Next, there is a discussion as to whether, if there is a rational explanation for these behaviors, they could still contribute to a diagnosis of insanity. Well, says the Talmud, it depends:

יכִי דָמֵי אִי דְּעָבֵיד לְהוּ דֶּרֶךְ שְׁטוּת אֲפִילּוּ בַּחֲדָא נָמֵי אִי דְּלָא עָבֵיד לְהוּ דֶּרֶךְ שְׁטוּת אֲפִילּוּ כּוּלְּהוּ נָמֵי לָא

לְעוֹלָם דְּקָא עָבֵיד לְהוּ דֶּרֶךְ שְׁטוּת וְהַלָּן בְּבֵית הַקְּבָרוֹת אֵימוֹר כְּדֵי שֶׁתִּשְׁרֶה עָלָיו רוּחַ טוּמְאָה הוּא דְּקָא עָבֵיד וְהַיּוֹצֵא יְחִידִי בַּלַּיְלָה אֵימוֹר גַּנְדְּרִיפַס אַחְדֵּיהּ וְהַמְקָרֵעַ אֶת כְּסוּתוֹ אֵימוֹר בַּעַל מַחְשָׁבוֹת הוּא כֵּיוָן דְּעַבְדִינְהוּ לְכוּלְּהוּ הָוֵה לְהוּ

The case is about a person who performs these actions in a deranged manner, but each action on its own could be explained rationally. With regard to one who sleeps in the cemetery, one could say that he is doing so in order that an impure spirit should settle upon him. [Although it is inappropriate to do this, as there is a reason for this behavior it is not a sign of madness.] And with regard to one who goes out alone at night, one could say that gandrifus took hold of him and he is trying to cool himself down. And as for one who tears his garments, one could say that he is a man engaged in thought, and out of anxiety he tears his clothing unintentionally.

What is Gandrifus? Koren vs Artscroll (and jastrow)

What might be this thing called gandrifus - (גַּנְדְּרִיפַס)? The Koren Talmud, whose online translation at Sefaria is the one that we usually cite, translates this word as a “fever that took hold of a person,” following the second explanation of Rashi:

דהיוצא יחידי בלילה אימור גנדריפס אחדיה אני שמעתי חולי האוחז מתוך דאגה ולי נראה שנתחמם גופו ויוצא למקום האויר…

“I have heard” Rashi says, “that gandrifus is a fever, and the person, goes outside to cool down.” But Rashi’s first explanation is more in keeping with a mental illness: “I have heard this is when a person is gripped by depression [da’agah, also worry].” But the Artscroll (Schottenstein) English Talmud has a completely different translation. Here it is:

אֵימוֹר גַּנְדְּרִיפַס אַחְדֵּיהּ- one could say that a fit of lycanthropy seized him.

In a footnote, the translators explain that “Lycanthropy is a type of melancholy, which comes from worry.” The Soncino English Talmud also translates the gandrifus as lycanthropy, though it leaves out the melancholy part. (Goldschmidt’s 1929 German translation makes no mention of wolves: “nachts allein ausgegangen sein, weil er von der Melancholie befallen wurde.” But the Hebrew ArtScroll skips this explanation entirely, and translates gandrifus according to Rashi’s second explanation, though it expands on it in a footnote.)

But hang on, surely something is amiss here. Lycanthropy, according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, means either “a delusion that one has become a wolf” or “the assumption of the form and characteristics of a wolf held to be possible by witchcraft or magic.” What does that have to do with depression?

But in fact, and as we shall see in some detail, the Artscroll translation appears to be the one that is most appropriate. Let’s begin with Marcus Jastrow and his famous dictionary, which has an entry for this strange word gandrifus. Here it is in the original:

So according to Jastrow, a person with gandrofus (there are variant spellings of the word in Hebrew) believes himself to be a wolf. But not just any wolf. A sad wolf. The word is a corrupt version of the Greek word λυκαθρωπία, lykthropia, meaning “wolf-like.” And you can even hear the similarity between the two words gan-dro-fus and (ly)kan-tro-py.

The Parallel Discussion in the Yerushalmi: “MAn-dog”

There is a similar passage in the Talmud Yerushalmi that lists the signs of insanity, and it uses a slightly different word, kunitrofus (קֻנִיטְרוֹפּוֹס), which is why Jastrow lists the two versions under the same entry. The English translation of this passage, also from Sefaria, is by Heinrich Guggenheimer, “a renowned mathematician who also published works on Judaism,” and who in 2015 at the age of 97.

סֵימָנֵי שׁוֹטֶה הַיּוֹצֵא בַלָּיְלָה וְהַלָּן בְּבֵית הַקְּבָרוֹת וְהַמְּקַרֵעַ אֶת כְּסוּתוֹ וְהַמְּאַבֵּד מַה שֶׁנּוֹתְנִין לוֹ. אָמַר רִבִּי הוּנָא וְהוּא שֶׁיְּהֵא כוּלְּהֶן בּוֹ דִּלָא כֵן אֲנִי אוֹמֵר הַיּוֹצֵא בַלָּיְלָה קֻנִיטְרוֹפּוֹס

. הַלָּן בְּבֵית הַקְּבָרוֹת מַקְטִיר לַשֵּׁדִים. הַמְּקַרֵעַ אֶת כְּסוּתוֹ כוֹלִיקוֹס. וְהַמְּאַבֵּד מַה שֶׁנּוֹתְנִין לוֹ קִינִיקוֹס. רִבִּי יוֹחָנָן אָמַר אֲפִילוּ אַחַת מֵהֶן. אָמַר רִבִּי בּוּן מִסְתַּבְּרָה מַה דְּאָמַר רִבִּי יוֹחָנָן אֲפִילוּ אַחַת מֵהֶן בִּלְבַד בִּמְאַבֵּד מַה שֶׁנּוֹתְנִין לֹו אֲפִילוּ שׁוֹטֶה שֶׁבְּשׁוֹטִים אֵין מְאַבֵּד כָּל־מַה שֶׁנּוֹתֵן לוֹ

The signs of an insane: One who goes out in the night, stays overnight in a graveyard, tears his clothing, and destroys what one gives to him. Rebbi Huna said, only if all of that is in him since otherwise I say that one who goes out in the night is a man-dog;One who stays overnight in a graveyard burns incense to spirits, he who tears up his clothing is a choleric person; Rebbi Jochanan said, even only one of these is proof. Rebbi Abun said, what Rebbi Jochanan said, even only one of these is reasonable only for him who destroys what one gives to him; even the greatest idiot does not destroy all one gives to him.

So according to the late Heinrich Guggenheimer, a kunitrofus is a “man-dog.” He certainly did his homework, because this is how it is translated in Henry Lidell’s classic Greek-English lexicon, first published in 1843, (and, fun bonus fact, Lewis Carroll wrote Alice's Adventures in Wonderland for Henry Liddell's daughter Alice).

Now would also be a good time to explain the etymology of the word werewolf, which according to Daniel Ogden’s very recent book The Werewolf in the Ancient World, probably comes from the Anglo-Saxon w(e)arg meaning outsider, “in which case werewulf is to have signified ‘outsider-wolf’ in origin” (p8).

Lycanthropy in the Ancient World

Perhaps the earliest legend of a human turning into a wolf comes from the Greek myth of Lycaon, which dates back to the sixth century BCE. Lycaon gave Zeus a human sacrifice, which made Zeus very angry. So angry, that he turned Lycaon into a wolf.

Another legend is the story of Petronius and the werewolf, which Ogden attested to around 66CE, in which a traveller is turned into a werewolf and secures the safety of the clothes he will need to transform himself back into a human by urinating on them as they lay in a graveyard. He is later identified as a werewolf when a wound on his neck is identified as the one inflicted on him while in lupine form. (There is a terrific animated video of the simplified story in Latin (!) with subtitles, and very much worth the four minute watch, available here.) There are many more versions, including the tale of Damarchus from around the same time, in which Damarchus is tricked into eating human flesh, and is transformed into a wolf. All of which is enough to show that the rabbis of the Talmud may have heard of these legends too.

Lycanthropy and Mental Illness

Lycanthropy, as the term is used today, does not mean the ability to transform oneself into a wolf (because, well, there is no such ability). Instead, it is the belief that one has been transformed into an animal, or the display of animal-like behavior suggesting such a belief. And there are case reports of this mental illness. Here is one, from a paper published in 1999 in the British journal Psychopathology:

Mrs T. is a 53-year-old Caucasian lady. She is divorced and lives in a residential home for recovered mentally ill. She has been diagnosed as epileptic since the age of 11. She is prone to suffer complex partial seizures in the form of epigastric aura, followed by turning the head to the left side, with loss of consciousness... She has been treated with several antiepileptics…At the age of 27 she went to Singapore with her husband who was working in the navy. She started to develop severe depression and suicidal ideas. So she came back to the UK and was admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Since then she has had 4 admissions mainly due to depression and suicidal attempts. She had one admission due to a manic attack. During this attack she had accelerated thoughts, disinhibited behaviour and speech, talking to strangers about having had oral sex.

At all her admissions she manifested delusions in the form of beliefs that her heart was not working or that she was dead or part of her body had died. After each discharge she returned to her normal level of functioning.

During her last admission, in 1996, she took an overdose of temazepam. She said that she did not intend to kill herself at that time. However, she was escaping from the belief that claws were growing in her feet. She found a support for her belief when the chiropodist could not cut her nails. When she was asked about the meaning of having claws she said that she was going to be ‘lunatic’. She could not give an explanation of the word lunatic more than changing into a helpless person. ... Her psychotic symptoms were treated with anti-psychotic medication. However, the frequency of fits was high during this time. Although she was stabilised in her mood after the last discharge, her husband found the whole situation very difficult.

In the last follow-up in the out-patient clinic she still had the belief that claws grew in her feet mainly at night when she was not wearing shoes and socks.

But lycanthropy is not limited to the British. The American Journal of Psychiatry also reported a case of lycanthropy, in which the patient, a forty-nine-year-old married woman, “presented on an urgent basis for psychiatric evaluation because of delusions of being a wolf” and “feeling like an animal with claws.” She suffered from extreme apprehension and felt that she was no longer in control of her own fate; she said, “A voice was coming out of me.” The report continues:

The patient chronically ruminated and dreamed about wolves. One week before her admission, she acted on these ruminations for the first time. At a family gathering, she disrobed, assumed the female sexual posture of a wolf, and offered herself to her mother.

This episode lasted for approximately 20 minutes. The following night, after coitus with her husband she growled, scratched, and gnawed at the bed. She stated that the devil came into her body and she became an animal. Simultaneously, she experienced auditory hallucinations. There was no drug involvement or alcoholic intoxication.

The patient was treated in a structured inpatient program…and placed on neuroleptic medication. During the first 3 weeks, she suffered relapses when she said such things as “I am a wolf of the night; I am a wolf of the day…I have claws, teeth, fangs, hair…and anguish is my prey at night…the gnashing and snarling of teeth…powerless is my cause, I am what I am and will always roam the earth long after death….”

She exhibited strong homosexual urges almost irresistible zoophilic drives, and masturbatory compulsions – culminating in the delusion of a wolflike metamorphosis...

By the fourth week she had stabilized considerably, reporting, “I went and looked into a mirror and the wolf eye was gone.” There was only one other short-lived relapse, which responded to reassurance by experienced personnel. With the termination of that episode, which occurred on the night of a full moon, she wrote what she experienced: “I don’t intend to give up my search for [what] I lack…in my present marriage…my search for such a hairy creature. I will haunt the graveyards…” She was discharged during the night week of hospitalization on neuroleptic medication.

This very ill woman was diagnosed with “pseudoneurotic schizophrenia.” Her symptoms, wrote the psychiatrists who authored this case report, “were organized about a lycanthropic matrix,” and included the following classic symptoms:

Delusions of werewolf transformation under extreme stress.

Preoccupation with religious phenomenology, including feeling victimized by the evil eye.

Reference to obsessive need to frequent graveyards and woods.

The causes of this terrible mental affliction include schizophrenia, manic-depressive psychosis, and psychomotor epilepsy. But there is also porphyria.

“Common to all the ‘scientific’ attempts at explanation mentioned here is the desire to make the actions of historical protagonists comprehensible in terms of modern categories. Even in the twentieth century, the sinister figure of the werewolf seems to spark the need for rationalization.”

Lycanthropy and Porphyria. Or not

Another possible cause of lycanthropy is the rare metabolic disease called porphyria, made famous as the cause of the madness of King George III. As a result missing enzymes (and there are several varieties of the illness) there is a build up of porphyrins in the body, which eventually become toxic. The condition is characterized by:

Severe photosensitivity in which a vesicular erythema is produced by the action of light. This may be especially noticeable in the summer months or in a mountainous region.

The urine is often reddish-brown as a result of the presence of large quantities of porphyrins.

Over the years the skin lesions ulcerate, and attack the cartilage and bone. Over a period of years structures such as the nose, ears, eyelids and fingers undergo progressive mutilation.

The teeth may turn red or reddish brown due to the deposition of porphyrins.

There are a few suggestions in the medical literature that lycanthropy might be explained by porphyria (like this paper, and this one). In his frequently cited 1964 paper, the British physician Leon Illis wrote that “the red teeth, the passage of red urine, the nocturnal wanderings, the mutilation of face and hands,the deranged behaviour: what could these suggest to a primitive, fear-ridden,and relatively isolated community? Fig 2 gives an obvious answer.” And the figure is shown below.

Image of a victim of porphyria. Could this be a case mistaken for a werewolf? From L. Illis. On porphyria and the aetiology of werewolves. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 1964: 57; 23-26.

But others are not so sure. In his excellent review paper “Werewolves and the Abuse of History,” the Dutch anthropologist Willem de Blécourt wrote that we need to be careful of a special group of amateur werewolf authors. The doctors.

Not having been trained in either history of folklore (or cultural studies), they have used selective texts to diagnose “the werewolf.” One of the results is that werewolf publications are now saddled with what is confusingly called “the werewolf syndrome,” namely hypertrichosis, a rare somatic condition that leaves its sufferers with hair either all over their body or in places where it usually does not grow….they are also connected to another very rare condition,“congenital erythropoietic porphyria” (or CEP). Further, within psychiatry there is now a recognized affliction called “lycanthropy,” denoting humans who are under the delusion that they have changed into a number of animals, among them, a wolf.

The problem, according to Blecourt, begins with the belief that the werewolf legend must have something tangible behind it. As Illis wrote in 1964, “a belief as widespread both in time and place as that of the werwolf [Illis’s spelling] must have some basis in fact. Either werwolves exist or some phenomenon must exist or have existed on which, by the play of fear, superstition and chance, a legend was built and grew.” But Illis based himself on only one late nineteenth century Dutch report, which was “was not even a wolf, but only a translation of a local term, denoting someone who can change into a cat, boar, monkey, deer, water buffalo, crocodile, or ant heap.” This author, according to Blecourt, “appears not to have been too concerned with European werewolves, but to have specifically drawn his werewolf picture to fit porphyria symptoms.” The problem is that many of the modern explanations are based on film depictions of werewolves, which themselves reinvented the legend, rather than being based on archival sources. “What stands out in the flood of recent popular werewolf publications” Blecourt lamented, “is that their authors, apart from occasionally branching out to people who are shifting into other animals, pay abundant attention to fiction, especially as expressed on television and in the cinema, and to “scientific” theories about the beast’s origin.”

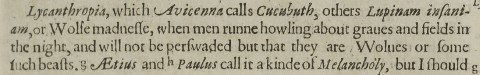

Lycanthropy and melancholy

Is there a connection between lycanthropy and depression? In his very helpful paper Medical and Neuropsychiatric Aspects of Lycanthropy, Miles Drake explained thar melancholy, one of the four humors that were thought to control our health and character, “came also to represent the pathological state of mood aberration. Lycanthropy was widely held to represent an excess of melancholy.” While we read this connection in the ArtScroll translation of the passasge in Chagigah, it can also be found in other texts. In 1586, the Italian Tomaso Garzoni published L’Hospedale de’ pazzi incurabilim, which was translated into English in 1600 as “The hospital for incurable fooles." In it, the author reported that

Among the humours of melancholy, the physicians place a kind of madness by the Greeks called Lycanthropia, termed by the latins insania lupina, or wolves furie: which bringeth a man to this point . . . that in Februarie he will goe out of the house in the night like a wolf, hunting about the graves of the dead with great howling, and pluck the dead mens bones out of the sepulchers, carrying them about the streets to the great fear and astonishment of all them that meet him ... melancholike persons of this kinde, have pale faces, soaked and hollow eyes, with a weak sight, never shedding one tear to the view of the world, a dry tongue, extreme thirst, and they want spittle and moisture exceedingly.

The connection between lycanthropy and melancholy (or what today we would call depression) was explicitly made by the English writer Robert Burton (1577-1640) in his massive work, The Anatomy of Melancholy, first published in 1621. Burton, who himself seems to have suffered from melancholy, wrote that the affliction can cause terrible physical suffering.

Melancholie abounding in their head, and occupieing their brane, hath deprived or rather depraved their judgements, and all their senses.., the force which melancholic hath, and the effects that it worketh in the bodie are almost incredible. For as some of these melancholike persons imagine, they are . . brute beasts .... Through melancholie they were alienated from themselves . . they may imagine, that they can transforme their owne bodies, which nevertheless remaineth in the former shape.

Burton noted that madness and melancholy are often conflated, and that the two can combine to produce religious visions and revelations, as well as lycanthropy:

There are other case reports about werewolves in the early modern period. Here is one from the French writer Simon Goulart’s Admirable and Memorable Histories, which was translated into English in 1607.

in the yeare 1541 who thought himselfe to bee a Wolfe, setting vpon diuers men in the fields, and slew some. In the end being with great difficultie taken, hee did constantlye affirme that hee was a Wolfe, and that there was no other difference, but that Wolues were commonlie hayrie without, and hee was betwixt the skinne and the flesh. Some (too barbarous and cruell Wolues in effect) desiring to trie the truth thereof, gaue him manie wounds vpon the armes and legges: but knowing their owne error, and the innocencie of the poore melancholic man, they committed him to the Surgions to cure, in whose hands hee dyed within fewe days after. ( page 387.)

“Lycanthropy is a rare phenomenon, but it does exist. It should be regarded as a complex and not a diagnostic entity. Furthermore, although it may generally be an expression of an underlying schizophrenic condition, at least five other differential diagnostic entities must be considered. ”

Summary

We have covered a lot of material, all of which was needed to explain not only the meaning of the talmudic word gandrofus, but also its use in the context of ancient nosology. Here is a summary:

The Talmud lists gandrofus as a kind of illness which while serious, is not enough to provide an exemption from the mitzvah to appear in the Temple.

ArtScroll, Soncino and Jastrow (but not Rashi) explain it to mean lycanthropy and (per ArtScroll,) melancholy.

Lycanthropy, the belief that a person could turn into a wolf, was a widespread belief in the ancient world, the medieval world, and the early modern world too. Rashi cites the legend.

Lycanthropy was associated with melancholy, an early term for depression.

And so gandrofus is the affliction of lycanthropy and depression.

Despite this, a person suffering from gandrofus is not exempt from the mitzvah of appearing in the Temple.

ArtScroll’s translation is the preferred one to Rashi’s.

QED.

Oh, and also, Binyamin was a werewolf.