Today’s page of Talmud starts a deep dive into to all things bloodletting. Here is a sample:

Shabbat 129a-b

Rab Judah said in Rab's name: One should always sell [even] the beams of his house and buy shoes for his feet. If one has let blood and has nothing to eat, let him sell the shoes from off his feet and provide the requirements of a meal therewith. What are the requirements of a meal? — Rab said: Meat; while Samuel said: Wine. Rab said meat: life for life. While Samuel said, Wine: red [wine] to replace red [blood]. ..For Samuel on the day he was bled a dish of pieces of meat was prepared; R. Johanan drank until the smell [of the wine] issued from his ears; R. Nahman drank until his milt swam [in wine]; R. Joseph drank until it [the smell] issued from the puncture of bleeding. Raba sought Wine of a [vine] that had had three [changes of] foliage.

…Rab and Samuel both say: If one makes light of the meal after bleeding his food will be made light of by Heaven, for they say; He has no compassion for his own life, shall I have compassion upon him!

Rab and Samuel both say: He who is bled, let him not sit where a wind can enfold [him], lest the cupper drained him [of blood] and reduced it to [just] a revi’it, and the wind come and drain him [still further], and thus he is in danger.

Samuel was accustomed to be bled in a house [whose wall consisted] of seven whole bricks, and a half brick [in thickness]. One day he bled and felt himself [weak]; he examined [the wall] and found a half-brick missing.

Rab and Samuel both say: He who is bled must [first] partake of something and then go out; for if he does not eat anything, if he meets a corpse his face will turn green; if he meets a homicide he will die; and if he meets swine, it [the meeting] is harmful in respect of something else.

Rab and Samuel both say: One who is bled should tarry awhile and then rise, for a Master said: In five cases one is nearer to death than to life. And these are they: When one eats and [immediately] rises, drinks and rises, sleeps and rises, lets blood and rises, and cohabits and rises.

Samuel said: The correct interval for blood-letting is every thirty days. Samuel also said: The correct time for bloodletting is on a Sunday Wednesday and Friday, but not on Monday or Thursday…

“Rabbi Yochanan said: the sages made blood letting in Israel like a healing that has no limit.”

Blood letting is mentioned in many places in the Talmud. For example, in Ketuvot (52b) there is a discussion that hinges on the frequency of the procedure. The issue discussed there is whether you should undergo therapeutic venesection - blood-letting - regularly (like using the gym) or save it for special occasions (like a birthday or anniversary)? The question of who should pay for a widow's blood-letting session depends on the resolution of this conundrum. If blood-letting is considered a rare or one-off intervention, then the costs of the procedure should be borne from the fixed proceeds from the widow's Ketuvah. But if the procedure needs to performed often and regularly, it is considered to be more like the ongoing expense of food; in that case the costs must be borne by the heirs of the deceased husband and not by the woman herself using up the proceeds of her Kutuvah. It's at this point in the discussion that Rabbi Yochanan speaks up, who tells us that “the sages made blood letting in Israel like a healing that has no limit.” In Israel blood-letting was performed on a regular basis, and so - at least in this particular case - the heirs were required to pay for it.

The Origins of blood letting

At its core, blood-letting depends on the principle of the four humors in the body, which seems to have come from the Greeks around the 5th century BCE. According to this theory, there are four humors or systems that regulate the human body. If they are in balance, all is good. But if that balance is upset, disease follows.

The four humors are blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. The only one of these that is readily accessible to the outside is blood, of course. So the idea grew that if a person was ill, it was because there was too much blood. Or as Galen put it, blood was the most dominant of the humors. And the treatment? To get rid of some of that unnecessary blood. And so bloodletting was born. The four humors were also thought to correspond to the four elements from which all matter is built, like this:

How to be a blood-letter

Brass scarificator circa 1840. The thirteen blades were drawn across the arm or leg, and the blood flowed out. Made by Tiemann & Co.; Manufacturers of Surgical Instruments & Every Description of Cutlery; No. 63 Chatham St.; New York.

There were various ways to remove the blood. You could use leeches, or you could cut the arms or legs and induce bleeding. And then there was a surgical procedure which was simple enough and rather brutal. You went to the blood letter and he sliced into your vein. After a while, when the blood-letter had determined that you'd lost just the right amount of blood, the wound was bandaged, and off you went, looking forward to being cured of whatever had led you to the blood-letter in the the first place. The procedure was thought to be the way to cure any number of illnesses, including fever and asphyxia (Yoma 84a). As we mentioned, it dates back at least to the 5th century BCE, and is mentioned in the writings of Erasistratus (300-260 BCE) who opposed the procedure, and Galen (c. 130-200 CE) who used it and taught that it was an important tool that could heal the sick.

Blood letting over the centuries

The procedure, which had been in use almost 2,000 years, only stopped being part of standard medical practice in the late 19th and early 20th century. Bloodletting certainly contributed to the death of an American President. Here is how I described the story in my book on influenza:

Not three years after he resigned as the first president of the United States, George Washington was on his deathbed. As a last-ditch effort to save him, doctors opened his veins to thwart the infection ravaging his throat. Washington endured four rounds of bloodletting, the last one only a few hours before he succumbed.

“I am just going,” Washington said to his secretary, Tobias Lear, at that point.

“He died by the loss of blood and the want of air,” said a family friend and doctor, William Thornton—who suggested that Washington could be reanimated by a transfusion of lamb’s blood.

Thankfully, the doctors decided not to proceed with the re-animation attempt. Writing in 1875, one Englishman could not bring himself to believe that the era of blood-letting was really over. "Is the relinquishment of bleeding final?" he wrote,

or shall we see by and by, or will our successors see, a resumption of the practice? This, I take it, is a very difficult question to answer; and he would be a very bold man who, after looking carefully through the history of the past, would venture to assert that bleeding will not be profitably employed any more.

But blood letting was far from over. It was even suggested as a therapy by doctors during a severe influenza outbreak at a British Army camp in northern France in the winter of 1916-17. Here is what they wrote, using the medical term “venesection” rather than the more brutal term “bloodletting.”

The doctors noted that venesection did not help, but the reason was probably that it had not been performed soon enough. Remember this was at the time of your grandparents and great-grandparents. And the name of journal in which this was published? The Lancet, named for the very implement used to perform the procedure.

“The importance of bloodletting, as a medicinal agent, in comparison with other means of cure, is shown in various aspects. It is a remedy the most frequently called for in general practice’ and often of itself, and without the aid of other means, accomplishes all we wish. ”

Modern Medicine and the Practice of Blood-Letting

There is absolutely no place for this intervention today, other than for a couple of rare disorders. One is polycythemia vera. In this illness, the body makes too many red blood cells (hence its name, poly=many, kytos=cells, hamia=blood), and one way to keep the illness in check is to remove those excess blood cells at a regular intervals. Another rare disorder that is sometimes treated with therapeutic blood-letting is hemochromatosis, in which there is a build up of iron in the body. But other than for these rare diseases, blood-letting, (called today phlebotomy or venepuncture, which do sound a whole lot more palatable but describe the same procedure) is harmful. Do not try this at home.

Having made this very clear, let's introduce some nuance. Palliative blood-letting may be useless, but from this it does not follow that it is a good idea to restore the hematocrit (the concentration of red blood cells in the blood) to normal in every disease state. For example, virtually all patients on dialysis (due to chronic kidney disease) become anemic, but in these patients, trying to restore the hemoglobin concentration to a higher level (~13g/dL for those interested) seems to be associated with increased risk, when compared with those in whom the hemoglobin level was lower. And when tiny premature babies get anemic, there does not seem to be an advantage to keeping the hemoglobin in a higher range (though to be fair, more research needs to be done). But these two examples do not in any way lend support to the notion that blood-letting is anything other than a really bad idea.

A prayer by the Patient

We no longer practice this useless intervention, but the prayer associated with it is worth recalling. Maimonides ruled (Berakhot 10:21) that before undergoing blood-letting, the patient pray the procedure be effective,and this ruling is found as part of normative Jewish practice, recorded in the (שולחן ערוך (אורח חיים רל ס׳ק ד:

הנכנס להקיז דם אומר "יהי רצון מלפניך ה' אלהי שיהא עסק זה לי לרפואה כי רופא חנם אתה". ולאחר שהקיז אומר "ברוך רופא חולים

Before undergoing blood letting say: May it be your will Lord my God, that this procedure will heal me, for you are an unconditional healer. And when it is finished he says: Blessed are you God, healer of the sick.

The medical procedures have changed, but the prayers have stayed the same.

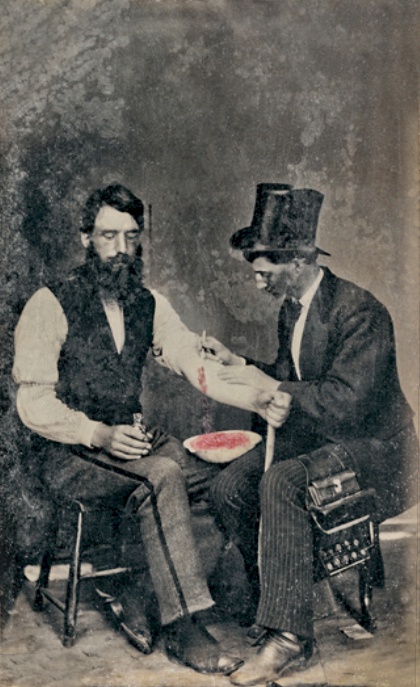

Photo of bloodletting in 1860. Yes, that's right, 1860. From the Burns Archive

[Re-posted (with a few changes) from Yevamot 72a]