Mayer Kirshenblatt. The Illegal Slaughter. From Mayer Kirshenblatt and Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, They Called Me Mayer July: Painted Memories of a Jewish Childhood in Poland Before the Holocaust. University of California Press. n.d. p114

חולין קכא,ב

הרוצה שיאכל מבהמה קודם שתצא נפשה חותך כזית בשר מבית שחיטתה ומולחו יפה יפה ומדיחו יפה יפה וממתין לה עד שתצא נפשה ואוכלו אחד עובד כוכבים ואחד ישראל מותרין בו

One who wishes to eat from the meat of a slaughtered animal before its soul departs may cut an olive-bulk of meat from the area of its slaughter, the neck, and salt it very well and rinse it very well [in water to remove the salt and blood,] and then wait until the animal’s soul departs, and then eat it. Both a gentile and a Jew are permitted to eat it [because the prohibition against eating a limb from a living animal is not applicable in such a case].

מסייע ליה לרב אידי בר אבין דאמר רב אידי בר אבין א"ר יצחק בר אשיין הרוצה שיבריא חותך כזית בשר מבית שחיטה ומולחו יפה יפה ומדיחו יפה יפה וממתין לה עד שתצא נפשה אחד עובד כוכבים ואחד ישראל מותרים בו

This teaching supports the opinion of Rav Idi bar Avin, as Rav Idi bar Avin said that Rav Yitzḥak bar Ashyan said: One who wants to be healthy should cut an olive-bulk of meat from the area of the slaughter, and salt it very well and rinse it very well, and then wait until the animal’s soul departs, and then both a gentile and a Jew are permitted to eat it.

Today we learn about a very strange (and disturbing) talmudic folk tradition. If you want to stay healthy, cut some meat from the throat of an animal that had been slaughtered by the usual method of shechita - but do so before the animal has died. Since there is a very strong prohibition against eating meat taken from a living animal, the Talmud goes out of its way to note that it does not apply in this case. The folk remedy apparently demanded that the meat be taken before the animal is dead - and so waiting would defeat the whole purpose.

Now this sounds pretty cruel. But since the Talmud brought it to our attention (and permitted or even encouraged it) we must take a detailed look into the question of how our modern sensibilities and our modern science might approach the complicated question of the relationship between animal suffering and shechita.

The new Belgian requirement for animal stunning

As of January 1st, 2019 Belgian authorities have essentially banned both the Muslim and Jewish methods of ritually slaughtering animals. In case you missed it, here is part of The New York Times report from Jan 5th:

Laws across Europe and European Union regulations require that animals be rendered insensible to pain before slaughter, to make the process more humane. For larger animals, stunning before slaughter usually means using a “captive bolt” device that fires a metal rod into the brain; for poultry it usually means an electric shock. Animals can also be knocked out with gas.

But slaughter by Muslim halal and Jewish kosher rules requires that an animal be in perfect health — which religious authorities say rules out stunning it first — and be killed with a single cut to the neck that severs critical blood vessels. The animal loses consciousness in seconds, and advocates say it may cause less suffering than other methods, not more…

“The government asked for our advice on the ban, we responded negatively, but the advice wasn’t taken,” said Saatci Bayram, a leader of the Muslim community. “This ban is presented as a revelation by animal rights activists, but the debate on animal welfare in Islam has been going on for 1,500 years. Our way of ritual slaughtering is painless…”

The idea for the ban was first proposed by Ben Weyts, a right-wing Flemish nationalist and the minister in the Flanders government who is responsible for animal welfare. Mr. Weyts was heavily criticized in 2014 for attending the 90th birthday of Bob Maes, who had collaborated with the Nazi occupation of Belgium in World War II and later became a far-right politician.

Animal rights groups applauded the legislation. When it was approved by the Flemish Parliament in June 2017, Mr. Weyts hailed the vote on Twitter, writing: “Proud animal minister. Proud to be Flemish…”

Rabbi Schmahl [a senior rabbi in Antwerp] cited another Belgian law that was recently enacted, to regulate home schooling — a common practice in his community — as an example of a pattern of laws in Europe making it increasingly difficult for observant Jews to live according to their traditions.

“It definitely brings to mind similar situations before the Second World War, when these laws were introduced in Germany,” he said.

It’s all there. A claim that shechita is less humane than slaughter by captive bolt; allegations that it’s all a plot by anti-semites (in the real sense of the word - targeting both Jews and Muslims); counter-claims that shechita is more humane than other methods and finally a throwback to the Holocaust (proving, once again, the accuracy of Godwin’s law). Two days later a New York Times editorial appeared: When Animal Welfare and Religious Practice Collide:

It should be obvious to any reader…that there is bound to be impassioned debate on the issue. And indeed animal-rights advocates and religious leaders have squared off on social media and the internet, citing volumes of scriptural injunctions and scientific studies…

The debate, moreover, is hardly new. Regulations across the European Union require stunning an animal before slaughter, a practice that generally means either firing a bolt into its brain or an electric shock…

The pretexts of some politicians does not mean all those who insist on stunning have dubious motives. Animal-rights activists have long campaigned, justifiably and successfully, for the humane treatment of animals destined for the table. Many earnestly believe that slashing the neck of a conscious animal causes more suffering than stunning the animal first…

Whether that’s so should be a matter of continuing study by the meat and poultry industries, animal scientists, veterinarians and governments. There is no question that the animals we raise for food should be exposed to the least suffering possible, just as there is no question that killing a healthy creature has enormous potential for cruelty.

But those who really care about the welfare of animals should be wary of making common cause with right-wing nationalists whose hostile intent is to make life more difficult for religious minorities. A real conversation on balancing animal rights and religious freedoms can take place only if it is free of hidden bigotry.

What we Used to believe about Animals and pain

“They eat without pleasure, cry without pain, grow without knowing it; they desire nothing, fear nothing, know nothing... ”

Just a few hundred years ago, any discussion about animals feeling pain would have been dismissed as nonsense. It was Rene Descartes (the one who gave us “I think therefore I am”) who opined that animals were automatons. Any signs that they were experiencing pain was, he believed, a reflex, and did not represent the suffering of a conscious animal. Vivisection, in which live animals were used in scientific experimentation, was standard practice in early modern Europe. Here is an example, written by Willam Harvey (d. 1657), the man who is credited with discovering the circulation of the blood:

If one performed Galen’s experiment and incised the trachea of a still living dog, forcibly filling its lungs with air by means of bellows, and ligated them strongly in the distended position, one would find, on rapidly opening the chest, a great deal of air in the lungs…

In his book Bad Medicine, the historian David Wootton added this:

In the 1970s the Royal Society made a film for schools that reproduced Harvey’s vivisections. I have met two people who were shown it at school; both told me that they could not bear to watch it all, and that some of their co-students fainted.

As we have seen previously, animals were regularly put on trial in talmudic times through to the middle ages. It’s a paradox that on the one hand we once thought of animals of being culpable for crimes, while on the other we believed them incapable of thought or experiencing pain. We know a lot more today. Animals feel pain. About this there is fortunately no more debate. But there is a question about how an animal that is slaughtered feels pain, and how that pain may be reduced.

Shechita and Pain

It has been a foundational belief by those who defend it in modern times that shechita is a painless and humane method of slaughter. “It is a popular myth that Shechita is a painful method of slaughter. In fact, there is ample scientific evidence to the contrary” said Henry Grunwald (OBE QC!) Chairman of Shechita UK. “The Shechita process requires the rapid uninterrupted severance of major vital organs and vessels which produces, inter alia, instant drop in blood pressure in the brain…and [the] irreversible cessation of consciousness and sensibility to pain… producing a painless and effective stun and instant insensibility – followed without delay by immediate death.” In the US, the Orthodox Union claimed that “shechita is more humane than the common non-kosher form of shooting the animal in the head with a captive bolt…The Humane Slaughter Act, passed into law after objective research by the United States government, declares shechita to be humane. For Torah observant Jews, it cannot be any other way.”

“Shechita itself, the act of animal killing, is designed to minimise animal pain. The animal must be killed by a single cut with an instrument of surgical sharpness, and in the absence of anything that might impede its smooth and swift motion. The cut achieves three things: it stuns, kills and exsanguinates in a single act. We believe that this is the most humane, or a most humane method of animal slaughter. ”

But as we make our way through the tractate Chullin, there is no mention of the pain of the procedure. And with very few exceptions that we will come to, it was not until modern times that anyone made the claim that we slaughter animals using shechita because it is as close to being painless as possible. We do it because that’s been a part of Jewish tradition.

Shechita and the EEG

In 1994, Temple Grandin, the great champion of humane slaughter observed that cattle did not yank away their necks during shechita. “All of them stood still during the cut and did not appear to feel it” she wrote, though she also noted that “whether or not ritual slaughter conforms to the requirements of euthanasia is a controversial question.” Since then others have looked into the question of brain activity as a marker of pain during shechita.

In 2009 a group of veterinarians in New Zealand hooked up fourteen Angus steers to an EEG, which measures the electrical activity in the brain. They were lightly anesthetized (the cows, not the veterinarians) and then slaughtered with an incision across the neck, “severing all tissues ventral to the vertebral column including the major blood vessels supplying and draining the head.” During the 30 seconds following this incision, the EEG showed significant changes leaving the scientists to conclude that “…there is a period following slaughter where ventral neck incision represents a noxious stimulus.” In a slightly different study on calves, the group concluded that the EEG responses were primarily due to noxious stimulation and not mainly as a result of loss of blood flow through the brain.

Ari Zivotofsky (he of the exotic kosher banquet) claimed that these experiments had “…zero relevance to shechita because the conditions used did not mimic shechita in terms of the knife’s size, sharpness, and smoothness.” He continues:

It is possible that cutting a cow’s neck with a short, blunt, non-smooth knife is indeed painful, while a shechita cut may be significantly less so or even totally devoid of pain. Does the animal feel no pain? Might it even be a pleasurable feeling, e.g., are endorphins released? I don’t know. But many people who have gotten a paper cut or who have been cut by a scalpel can attest to the fact that while the cut is taking place it is essentially not sensed and it is only later that the pain kicks in. And in the case of shechita, the animal will be senseless by that point.

It would be hard to believe that the sensation of having your neck sliced open would be similar to that of getting a paper cut - and harder still to think that it might even be pleasurable. But here is a suggestion: do the experiment (though not on your friends) and let us know.

But don’t take my word for it. Temple Grandin herself wrote that “there is a need to do research with EEG measurements when the special…kosher knife is used by a trained person.”

In fact brain activity has been compared between shechita and captive bolt stunning, and the results did not bode well for shechita. Here is one study published in 1988 in the Veterinary Record:

Captive bolt stunning followed by sticking one minute later resulted in immediate and irreversible loss of evoked responses after the stun. Spontaneous cortical activity was lost before sticking in three animals, and in an average of 10 seconds after sticking in the remaining five animals. The duration of brain function after shechita was very variable, and particularly contrasted with captive bolt stunning with respect to the effects on evoked responses. These were lost between 20 and 126 seconds (means of 77 seconds for somatosensory and 55 seconds for visual evoked responses) and spontaneous activity was lost between 19 and 113 seconds (mean 75 seconds) after slaughter.

The authors did add a note of caution: “…evoked responses do not represent a conscious awareness of the stimulus but are produced by neural activity at a rudimentary level which precedes conscious awareness.” But even so, these findings must raise the concern that the animals had a degree of brain activity for far longer after shechita compared to captive bolt use. And back to Grandin again: “Penetrating captive bolt, when it is applied correctly, will induce instant insensibility and unconsciousness, because visually evoked potentials are eliminated from the brain.” So there it is again: instant versus not-so-instant.

Shechita and the time to loss of CONSCIOUSNESS

Frequency distribution of the cattle according to time to collapse following halal slaughter without stunning. From Gregory N.G.et al. Time to collapse following slaughter without stunning in cattle. Meat Science 2010: 85; 66–69.

While it is often claimed by those who support shechita that it causes an immediate loss of consciousness (see above, Henry Grunwald the OBE QC), this is not to be the case. Grandin, who collected data from five kosher plants in different countries noted a huge variation: from as little as eight seconds to as long as a full two minutes. (Average times were somewhere between 15 and 35 seconds.) As we have seen, when properly applied, a captive bolt captive bolt provides an instant loss of consciousness.

One 2009 study studied the time to collapse following slaughter without stunning in cattle following halal slaughter (which is not the same as shechita, but it’s not much different either). It reported that 14% of the cattle collapsed and subsequently raised themselves to stand on all four feet before collapsing again. There was a twenty second interval, on average, between the first and final collapses. “This brief recovery in behaviour,” the authors point out,” has not been noted before because cattle are usually restrained during the main part of the bleeding period following slaughter without stunning.”

You are not helping

One thing that certainly does not help the case for shechita are wild claims like the one below. It comes from a book called TNT Torah Novel Thoughts, authored by “Anonymous” (and brought to my attention by an astute Talmudology reader). The claim is so bizarre that it is reproduced here in the original:

If the claim that “kosher animals were created with nerves ending at their shoulders, thus circumventing any feeling of pain” sounds ridiculous, that’s because it is. Does Anonymous believe that there are no cutaneous nociceptive nerve endings in cattle above the neck? If so, has he (or she) ever patted the neck of a cow or a horse? The cranial nerves in cattle, “have in general the same superficial origin as in the horse” wrote Septimus Sisson in his classic Textbook of Veterinary Anatomy (p. 717). There are some minor differences of course; the oculomotor nerve is slightly larger in the horse, and the superior buccal nerve crosses the masseter much lower in cattle than in the horse. But none of these comes anywhere near to the claim made by Anonymous. You could check this by reading Veterinary Neuroanatomy and Clinical Neurology (4th Edition). Then, if you have time, you could review Comparative Anatomy of the Horse, Ox, and Dog: The Vertebral Column and Peripheral Nerves, or its companion Comparative Anatomy of the Horse, Ox, and Dog:The Brain and Associated Vessels. You will find that it is the similarities between the species that is remarkable.

Schematic illustration of the autonomous and cutaneous distribution of nerves pertaining to the head of the (A) dog, (B) horse, and (C) ox. O = ophthalmic nerve; Mx = maxillary nerve (* = also within the maxillary distribution of the horse); Mn = mandibular nerve. From Levine J, et al. Comparative Anatomy of the Horse, Ox, and Dog:The Brain and Associated Vessels.

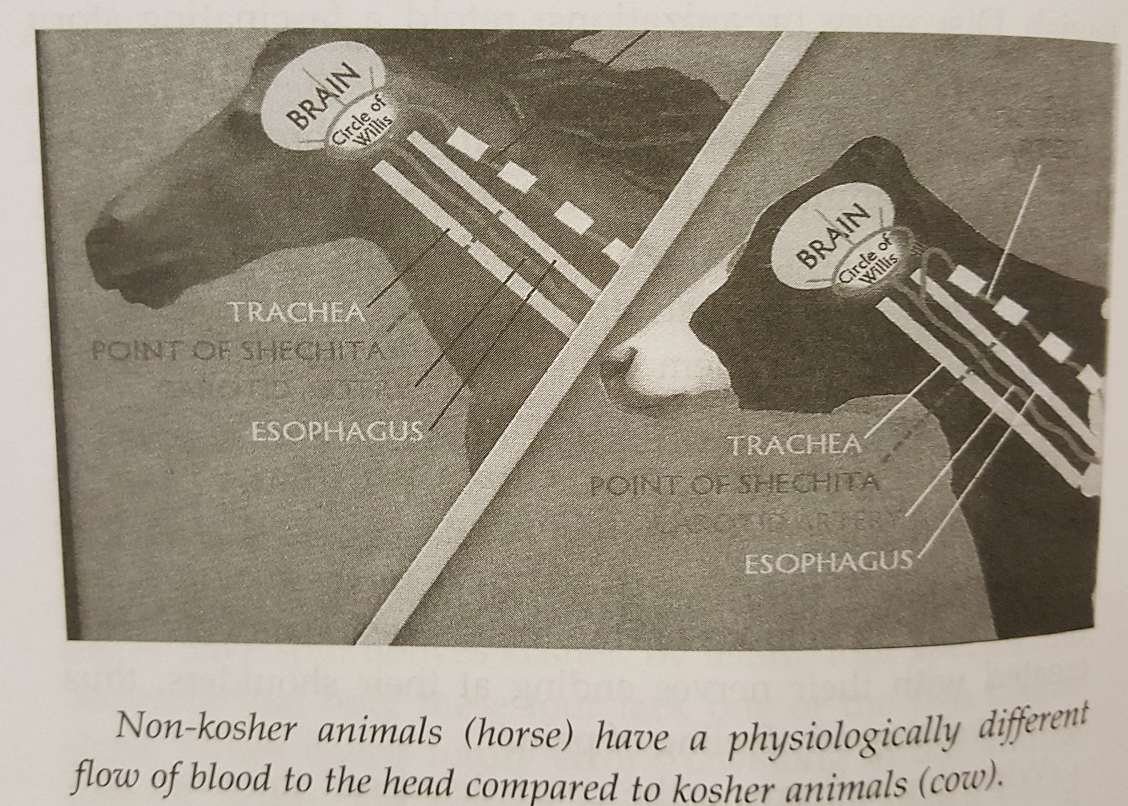

And what about the claim that there is a “physiological difference between the blood flow of non-kosher animals and kosher ones” (and that this information “could only be Divine")? Well, this too is wildly inaccurate. Of course there are some differences between species. For example, in horses, the Circle of Willis at the base of the brain is supplied by the internal carotid and basilar arteries. In cattle, the blood supply to the circle is via the internal carotid, maxillary, occipital, and vertebral arteries. And so, in cattle “the cerebrum receives a mixture of blood from all sources.” But there is no important physiologic difference in the blood flow of a horse and a cow.

The Talmud itself notes this. In the next tractate, Bechorot (10b) we read of a donkey that was killed because its owner wished to practice the technique of shechita on it (ששחטו להתלמד בו). Clearly then, the equine and bovine species are as good as identical in terms of their anatomy as it relates to ritual slaughter.

Commonly heard refrains about Shechita, and what to do about them

Those who oppose shechita are anti-Semitic

Do not respond to criticism of shechita with an ad hominem attack that the critic is an anti-semite. Stop worrying about the motives of those who question whether shechita is more or less humane than other methods of slaughter (like this Star-K website did). Yes, some people who do so are decidedly anti-semitic, but many who defend shechita are pro-semitic, and they are not disqualified from the debate. Discuss the science, not the motives of people. Fight any anti-Semitism rigorously, but separately.

2. There is scientific data showing that shechita is humane

This is true, but much of this data is unreliable or was produced using equipment that we have now improved. For example, In 2004 an S.D. Rosen published Physiological insights into Shechita in The Veterinary Record. Among other things, Rosen cited a 1976 book published by Feldheim together with the “Gur Aryeh Institute for Advanced Jewish Scholarship” titled Shechita, Religious, Historical and Scientific Scholarship. And in this book (stay with me) the cited scientific literature included (and contained graphs from) a 1963 paper (Levinger, Shechita and animal psychology), and a 1929 paper (Stahlstedt, Some attempts to obtain, by means of physiological experiments, an objective basis for an opinion as to cruelty alleged to be attendant on the Jewish ritual method of slaughtering cattle). That’s not nearly good enough. (I tried, but could not obtain a copy of this book published nineteen years ago, which perhaps contains the kind of modern data that is needed. Does anyone have a copy?)

3. “Of course” shechita is humane

Don’t claim that shechita “has been established over centuries to be the most humane form of animal slaughter” without the scientific data to support this claim. (For another example see the Rabbinical Assembly here.) There has been very little published research on the methods of shechita. (There appears to be more research about halal). If shechita is as humane as say, the captive bolt, (as measured by EEG tracings or evoked potentials,) then a head to head (sorry) study should be performed to compare the two. This would be a very good use of the resources available to the major kashrut organizations in the US, the UK, Israel, and beyond.

“Much discussion on ritual slaughter discusses humaneness, with accusations that Shechita is inhumane. Such language, with respect, is unconstructive. True humane slaughter requires the complete elimination of pain and distress, which is unachievable. Defining humaneness in terms of risk management is more realistic: recognising slaughter’s inherent unpleasantness, and the universal need for strategies to minimise suffering… Unless the state outlaws all slaughter, its object is avoidance, not elimination, of pain and suffering. ”

3. Shechita cannot be banned because it would violate our rights to religious freedom

The argument that shechita cannot be questioned or banned because it impinges on our religious freedom is not a strong one. In the modern and (somewhat) enlightened societies in which most of us live, we place limits on the freedoms to practice religion. In the US and many others countries, for example, the wishes of a Jehovah’s Witness parent who refuses permission for a life-saving blood-transfusion for their child have been consistently overruled. The rights to perform female circumcision are also curtailed – even if they are claimed to be part of a religious system. If a religion practices that which is considered immoral or unethical, then these practices should be regulated or abolished. True, this may place some religious practices like shechita or circumcision in a precarious position, but that this the price that, on average, may be worth paying. Think about this.

4. The whole purpose of shechita is a quick and painless death

This suggestion is not found anywhere in the Talmud. The word for suffering - צער - appears only a single time in the entire tractate of Chullin. (It is in the context of a suggestion to cut the hooves of a donkey to prevent them from kicking someone. So actually there is no mention of suffering in connection with the rules of shechita.) The word for kindness - חסד - does not appear at all. And neither of these words appears anywhere in the laws of shechita found in the Shulchan Aruch - The Code of Jewish Law.

But there is a far more problematic example that challenges any claim that animals must be shechted because this - and only this - can reduce suffering. It concerns the Ben Pakua, (lit, “the offspring that has broken through”) which is a viable calf found in utero after the shechita of its mother. Such an animal may be slaughtered and eaten without shechita. Let me repeat that. A viable calf found in utero may be eaten without shechita. In fact according Rabbi Shimon ben Shezuri, even if that calf grew up to be five years old, “its mother’s shechita purifies it” and it may therefore be killed and eaten without shechita.

Practically speaking though, it is not allowed to eat a Ben pakua without shechita. If you thought that the reason is that because shechita is so humane, and so it is the only way a Jew may eat meat, you are wrong. The Talmud and later sources have no such concerns. The reason it must be slaughtered with shechita is to prevent confusion. The farmer might mix up (דלמא אתי' לאחלופי בשאר בהמות) the Ben pakua with a non Ben pakua animal; the latter would then killed without shechita when in fact shechita was needed. That’s the reason we require a Ben pakua to be eaten only after shechita. But to our point, there is absolutely no mention of the need for shechita out of any concern for the pain or suffering of the animal. None.

But this does not imply that animal suffering was ignored. Among the earliest suggestions that shechita was practiced to minimize pain can be found in the Sefer Hachinuch (The Book of Education). It was written anonymously sometime in the thirteenth century but not published until 1523, and was attributed to R. Aharon Halevi of Barcelona.

“ שהרחיקה ממנו התורה דם כל בשר מה שידעתי. ואומר גם כן על צד הפשט כי מצות השחיטה היא מאותו הטעם, לפי שידוע כי מן הצואר יצא דם הגוף יותר מבשאר מקומות הגוף, ולכן נצטוינו לשחטו משם טרם שנאכלהו, כי משם יצא כל דמו ולא נאכל הנפש עם הבשר

ועוד נאמר בטעם השחיטה מן הצואר ובסכין בדוק, כדי שלא נצער בעלי החיים יותר מדאי, כי התורה התירן לאדם למעלתו ליזון מהם ולכל צרכיו, לא לצערן חינם, וכבר דברו חכמים הרבה באיסור צער בעלי חיים ... אם הוא אסור דאוריתא, והעלו לפי הדומה שאסור מדאוריתא.

The Torah forbids any blood from being eaten, and the command to perform shechita is based on the very same reasoning. We know that blood can leave the body through [an incision in] the neck quicker than it can from any other place. We were therefore commanded to shecht an animal’s neck before eating it, because it is from there that all of its blood will leave, and so we will not eat its soul [a reference to blood] with the meat...

Another reason that we must perform shechita at the neck with an approved knife is so not to be too cruel to the animals. For the Torah gave us permission to gain nourishment from them but this does not allow us to cause pain to them for no reason...And the rabbis have stated that the prohibition against animal cruelty comes from the Torah itself.

”

By any measure, this sentiment was far, far ahead of its time; recall what Descartes was thinking and Harvey was doing in the sixteenth century. But you will find that simply declaring that the reason for shechita is that it is “the most humane method of slaughter” is not really supported in classical Jewish texts until much later (if at all).

As but one example, consider the important commentary on the Shulchan Aruch called Pri Megadim by Joseph ben Meir Teonim (1727-1792). According to the Bar Ilan Project, the work has become “one of the primary explanations to this code of Jewish Law. There are super-commentaries on it, as well as abbreviated versions…Nowadays, the Pri Megadim is published at the end of each volume of the Shulkhan Aruch in almost every edition, and in some modern editions can be found on the very folio of the code.” And what does the Pri Megadim have to say about suggesting that the entire reason for shechita is to reduce cruelty? He says this, right in his introduction to the Laws of Shechita:

A reason given for this mitzvah [of shechita]…is because of the [prohibition against consuming] blood…and in addition because of the laws preventing cruelty to animals… and the reason that it is forbidden to use a damaged knife blade because of the issue of cruelty to animals.

However, everyone else has already written that one should not give reasons for any of the mitzvot. And even though in a few books the reasons are suggested, they should be paid no attention, as I will explain later…

“טעם מצוה זו הביא האליהו רבא בשם ספר החינוך דרוב דם יוצא מצוואר כדי שיצא הדם ועוד משום צער בעלי חיים ומוכיח מכאן דצער בעלי חיים דאורייתא עיין בספר החינוך סימן ת”מ וכן בסכין פגום אסור משום צער בעלי חיים יעויין שם

אמנם כבר כתבו כולם שאין ליתן טעם על שום מצוה וכן חמש הלכות שחיטה אף שבקצת ספרים נמצאין טעמים עליהן אין להשגיח עליהם ובמקומו אבאר כ”א בעזה”י

”

There are of course hundreds of other references to shechita and cruelty in the works of those who rule on Jewish law from the sixteenth century to contemporary times. (I’ve found at least 300 of them, but have not yet had the time to review them. It would be a great topic for a PhD.) But these are all ex post facto. And if that doesn’t convince you, you might want to read our three-part series on the folly of trying to reconcile Jewish Law with contemporary science.

5. Captive bolt use is worse than shechita because it goes wrong so often

Don’t compare the best of shechita (quick and painless) with the worst of captive bolt use (incompetent and unreliable). In her Recommended Captive Bolt Stunning Techniques for Cattle Temple Grandin suggested as an industry standard that 95% or more of the animals are rendered insensible with one shot whether penetrating or not. Under US Department of Agriculture (USDA) regulations (9 CFR Ch. III, 313.15) “captive bolts shall be of such size and design that, when properly positioned and activated, immediate unconsciousness is produced.” When Gradin studied the efficacy of penetrating captive bolt stunning of cattle, she found that among steers and heifers, 0.16% had signs of returning to sensibility, and 1.2% of bulls and cows did. “Return-to-sensibility problems” she wrote, “were attributed to storage of stunner cartridges in damp locations, poor maintenance of firing pins, inexperience of the stunner operator, misfiring of the stunner because of a dirty trigger, and stunning of cattle with thick, heavy skulls.” In a study of addressing the complications during shechita and halal slaughter without stunning in cattle, the authors estimated that 10% or more cattle develop complications during the bleeding period during normal halal and shechita slaughter. If this figure is accurate, the shechita organizations must address and improve their regulations. And if it is not, these same bodies should publish the evidence that shechita has fewer complications than captive bolt use.

6. If shechita is banned I would never be able to eat meat

That’s true. But so what? Slavery (or some form of it) is regulated in the Torah, and its rules and regulations are discussed in the Talmud. But we don’t own slaves, and find the thought morally repugnant. There are no Jews complaining that the thirteenth amendment to the US Constitution banning slavery was unfair, because hey, the Talmud says we can have slaves. Some things must be given up when the failure to do so is morally untenable.

7. Even if procedures like stunning or the captive bolt are shown to be more humane, we could never adopt them because of the laws of shechita.

Well, not so fast. Of course there are segments of the orthodox Jewish population that would never adopt these practices, because, well, the science is wrong and suspect and anyway of course shechita is humane see above). But there are large segments of the orthodox Jewish world who agree that Judaism has nothing to fear from evolving and adapting to new situations.

For centuries the traditional way of slaughtering cattle was known as casting, in which the animal was inverted onto their back before the shechita. (That’s why the drawing of the cow at the top of this piece is lying on its back.) But it is without doubt cruel and stressful to the animal. At least that’s what Temple Grandin thinks. “Cattle resist inversion she wrote, “and twist their necks in an attempt to right their heads.”

Around 1927 the Weinberg Casting Pen was developed (“by Mr. J.W. Weinberg an orthodox Jew and and a tailor by trade”). It was a padded stall that rotated mechanically and so did away with traditional methods of casting. The device was reviewed in Britain by the Veterinary Journal of that year. It noted that “the Shechita Board claim that their form of killing is humane, but the casting, i.e., getting the animal into the correct position for its throat to be cut, is not free from criticism.” And then this:

…the outstanding merit of the pen is that vigorous and restless animals which under existing methods might have to undergo long minutes of suffering and terror, often attended by severe injuries, are by its use cast and brought into the required position for the cut with the same rapidity and freedom from pain as the quiet ones. Even the greatest of the cruelties any of the present methods of casting would thus be brought to an end by the adoption of the mechanically working pen.

From Temple Grandin and Joe Regenstein, here.

And so it was. The Weinberg pen became widely used and with it a traditional and cruel practice was ended. (Admittedly casting was not a requirement for shechita itself, but a way to prepare for it). But things did not stop there. The Weinberg pen still involved turning large cattle upside down, which remained far from desirable. A new pen, approved by the American Society for the Protection of Cruelty to Animals allowed shechita to be performed with the animal standing in its normal position. “Very little pressure was applied to the animals by the rear pusher gate in the ASPCA pen” we learn from experts in animal welfare. “Head holders were equipped with pressure limiting devices. The animals were handled gently and calmly. It is impossible to observe reactions to the incision in an agitated or excited animal. Blood on the equipment did not appear to upset the cattle. They voluntarily entered the box when the rear gate was opened. Some cattle licked the blood.”

When the device was rolled out in 1964, The New York Times reported that “Rabbi Israel Kiavan, executive-Vice president of the Rabbinical Council of America, a prominent Orthodox group, hailed the Society's announcement as dramatic break through preparing animals for slaughter." But although this addressed the preparation of the animal and not the shechita itself, this new position could impede the action of the shochet who now had to cut against gravity. So it was in fact a practice that might impair kosher slaughter. In an undated responsa Rabbi Moshe Feinstein ruled that shechita of a large animal was permitted (אבל כשיקשרו ראש הבהמה למעלה סובר אני שיש להתיר אף לכתחלה ) when the animal was in an upright position. Again, this innovation addressed the pre-shechita set up, but it shows how traditional shechita methods were greatly improved upon, with a little help from some clever engineers, and then approved by rabbinic authorities.

Another example of the way shechita laws may be open to improvements, while receiving the imprimatur of even Orthodox Judaism is that of using inhaled anesthetics prior to shechita. Again, it was Rabbi Moshe Feinstein who was asked whether this procedure was permitted. Yes, he opined, although he thought it was a measure imposed “by those who hate Israel.”

אם יש מקום להתיר להוליך הבהמות לתוך תא שבתוכו געז /גז/ כ"ב אדר תש"כ. מע"כ ידידי הרב הגאון המפורסם כש"ת מוהר"ר יוסף מרדכי בוימעל שליט"א

הנה בדבר שרוצים מהמדינה להנהיג להוליך הבהמות לתוך תא שבתוכו מזרימים געז ומשהין אותן שם זמן קצר עד שמשפיע על מרכז העצבים ומתבטלים מזה חושיה והרגשותיה למשך זמן קצר וכשיעבור הזמן הדרא לבריאותה לכל חושיה והרגשותיה כמתחלה דהוא כמתעוררת מן השינה, אם הוא אמת ברור שלא נתקלקל בזה כלום מדברים המטריפים איני רואה בזה שום איסור שודאי אם ירדימו אותה כמו שמרדימים חולים קודם שעושין הרופאים להם אפעריישאן שאין מרגישים כלום בחתיכת בשרם לא היה שום חשש בהשחיטה וכדכתב כן גם כתר"ה דלא נמצא שהבהמה צריכה להיות ערה בשעת השחיטה

ואין לומר דיש אולי לחוש שמא לא אמדו יפה והיה שם געז במדה שתמות אבל שמ"מ תחיה זמן קצר שהיא מסוכנת, דודאי לענין המדת חסידות שאין בזה איסור יש לסמוך על האומדנא דהבקיאין ועל מה שחוששין להפסדם דהיתה מדה מועטת שאם יעבור זמן קצר תחזור לאיתנה כמקדם. ולכן כשיהיה פירכוס אחר שחיטה מותרת אף להמדת חסידות

אבל מ"מ צריך להשתדל בכל האפשר לבטל גזירה זו ששונאי ישראל רוצים להנהיג והשי"ת יעזרנו. ידידו מוקירו, משה פיינשטיין

Looking back, looking forward

After the 1933 Nazi ban on shechita without pre-stunning, the great posek R. Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg made a huge effort to convince his rabbinical colleagues that it could be permitted. As carefully documented in Marc Shapiro’s book, “almost every rabbi who responded to Weinberg opposed any change in the traditional method of shechita, under all circumstances…the pressure against change was so great that those who initially agreed with Weinberg later retracted their opinions when confronted with the weight of opposing rabbinic authority.”

Changes around the edges of the methods of shechita have certainly been accepted by the Orthodox community, but they need to do more. Produce the evidence that traditional shechita is not less humane than other forms of slaughter, or be prepared for further demands from those not only concerned with the right to religious freedom, but with animal welfare too.

From Legal Restrictions on Religious Slaughter in Europe, Law Library of Congress March 2018.