Today’s page of Talmud teaches that there are two kinds of divine commands. There are logical commands, things that Jews could have figured out without the Torah, like the prohibition against murder. And then there are commands for which there appears to be no logical reason. Had they not been written in the Torah, we would not have deduced them. And the classic example of the latter is the prohibition against eating pork.

יומא סז, ב

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן, ״אֶת מִשְׁפָּטַי תַּעֲשׂוּ״ — דְּבָרִים שֶׁאִלְמָלֵא (לֹא) נִכְתְּבוּ דִּין הוּא שֶׁיִּכָּתְבוּ, וְאֵלּוּ הֵן: עֲבוֹדָה זָרָה, וְגִלּוּי עֲרָיוֹת, וּשְׁפִיכוּת דָּמִים, וְגָזֵל, וּבִרְכַּת הַשֵּׁם. ״אֶת חוּקּוֹתַי תִּשְׁמְרוּ״ — דְּבָרִים שֶׁהַשָּׂטָן מֵשִׁיב עֲלֵיהֶן, וְאֵלּוּ הֵן: אֲכִילַת חֲזִיר, וּלְבִישַׁת שַׁעַטְנֵז, וַחֲלִיצַת יְבָמָה, וְטהֳרַת מְצוֹרָע, וְשָׂעִיר הַמִּשְׁתַּלֵּחַ

וְשֶׁמָּא תֹּאמַר מַעֲשֵׂה תוֹהוּ הֵם, תַּלְמוּד לוֹמַר: ״אֲנִי ה׳״, אֲנִי ה׳ חֲקַקְתִּיו, וְאֵין לְךָ רְשׁוּת לְהַרְהֵר בָּהֶן.

The Sages taught with regard to the verse: “You shall do My ordinances, and you shall keep My statutes to follow them, I am the Lord your God” (Leviticus 18:4), that the phrase: “My ordinances,” is a reference to matters that, even had they not been written, it would have been logical that they be written. They are the prohibitions against idol worship, prohibited sexual relations, bloodshed, theft, and cursing the Name of God.

The phrase: “And you shall keep my statutes,” is a reference to matters that Satan and the nations of the world challenge because the reason for these mitzvot are not known. They are: The prohibitions against eating pork; wearing garments that are made from diverse kinds of material, i.e., wool and linen; performing the ḥalitza ceremony with a yevama, a widow who must participate in a levirate marriage or ḥalitza; the purification ceremony of the leper; and the scapegoat.

And lest you say these have no reason and are meaningless acts, therefore the verse states: “I am the Lord” (Leviticus 18:4), to indicate: I am the Lord, I decreed these statutes and you have no right to doubt them.

This prohibition against eating pork is perhaps one of the most defining features of the laws of kashrut. “Want some bacon?” Vincent asks Jules in the classic 1994 movie Pulp Fiction, as the two hitmen are sitting in the Hawthorne Grill. “No man, I don't eat pork” replies Jules. Vincent is incredulous.

“Are you Jewish?”

“Nah, I ain't Jewish, I just don't dig on swine, that's all.”

Today we are going to talk about the prohibition about eating bacon, and then pivot to another forbidden food, catfish.

“Alongside circumcision and Sabbath observance, the prohibition against pork is considered one of the clearest identifiers of what a Jew does and, as such, who is a Jew.”

From here.

Cursed be he who raises swine

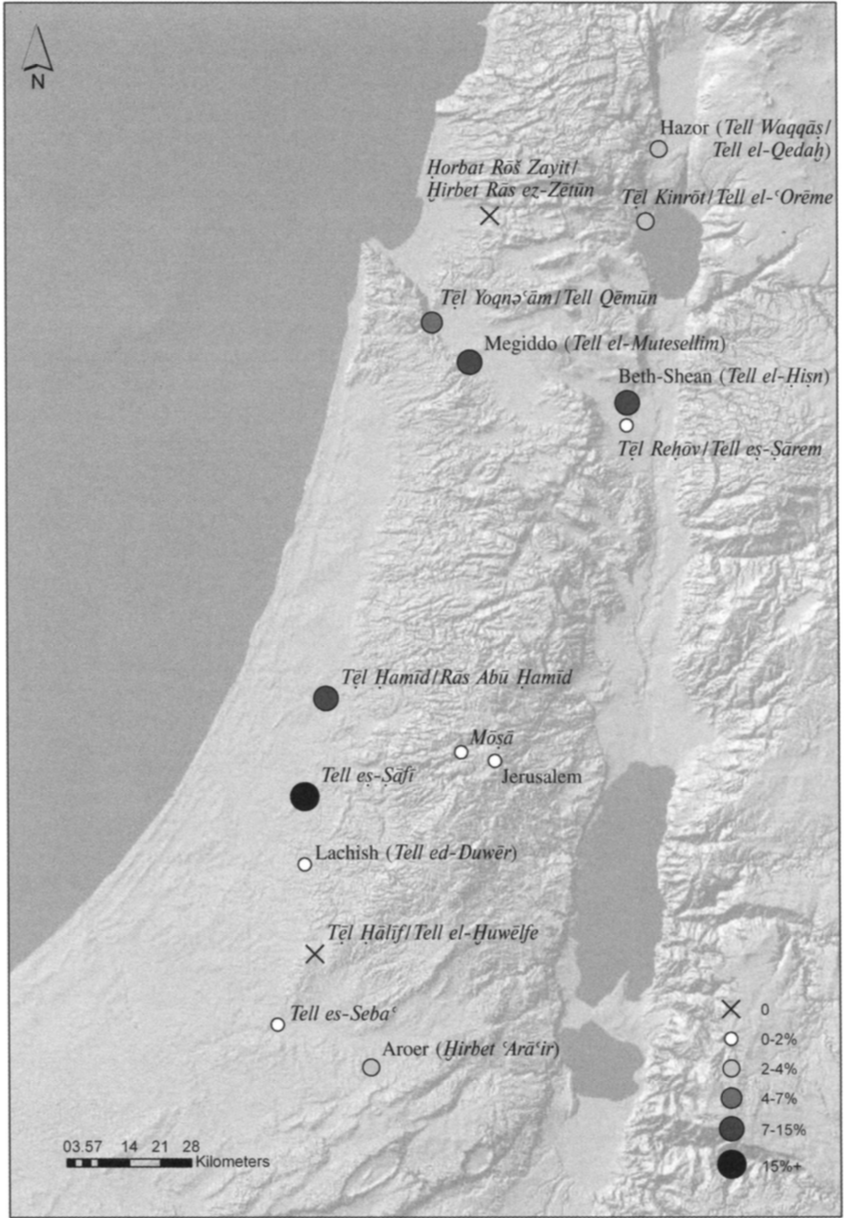

The prohibition against eating pork was so fundamental that the rabbis extended it to cover raising the animal too. “Cursed be he who raises swine,” they said in tractate Menachot (65b). Because this command was so deeply rooted, it has been long taken as a given that archeologists could use the presence (or absence) of pig remains to distinguish a Philistine from an Israelite settlement. For example, in known Philistine sites from Iron Age I (~950-780 BCE) like Ashdod and Ekron, pig bones account for 7-19% of the animal remains, depending on which strata you are excavating. This is a much higher percentage than is found in Israelite settlements of the same period. But in 2013 this assumption was challenged by a group of top-notch Israeli archeologists (including the controversial Israel Finkelstein) who reviewed the evidence for it. They studied data from 35 sites in Israel, and found a remarkable trend. In the territory of what was once the Northern Kingdom of Israel, pig remains account for 3-7% of all animal remains. But in the Southern Kingdom of Judah, pig remains are almost absent. (The site of Aroer is a bit of an anomaly, with more than 3% pigs. However this site seems to have been a rest stop for many international travelers and so may have served a more international cuisine.) There was a dichotomy between the kingdoms of Israel and Judah that was manifest in whether they ate pork.

Sapir-Hen, L. Bar-Oz, G. Finkelstein, I. Pig Husbandry in Iron Age Israel and Judah. New Insights Regarding the Origin of the "Taboo." Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins (1953-), Bd. 129, H. 1 (2013), pp. 1-20.

Why was there a rapid rise in the frequency of pigs being eaten in northern Israelite sites during Iron Age II (the period between 870 and 680 BCE)? Among the answers proposed is that “the pig taboo could have been another Judahite cultural trait that was opposed to the situation in the north, and which the authors [of the Torah] wished to impose on the entire Israelite population.” Alternatively, it may have been a result of the larger population found in the Northern Kingdom of Israel. “This process” wrote the authors of the paper Pig Husbandry in Iron Age Israel and Judah “brought about shrinkage of the open areas that are important for sheep/goat husbandry, and could have forced the Iron Age IIB population to a shift in meat production, breeding smaller herds of sheep and goats and concentrating more on pigs, which could supply large and immediate sources of meat.” In contrast, the population of the Kingdom of Judah was much smaller than that of Israel. Hence they had more open space to raise livestock.

By the way, it was the Philistines who were responsible for importing European type pigs into the Middle East. Dr Merav Meiri of the Department of Zoology at Tel Aviv University analyzed the DNA of ancient pigs in the area, and found that they possessed a European gene signature. This raises the possibility that European pigs were brought to the region by the Sea Peoples who migrated to the Levant around 900 BCE, bringing their pigs with them.

“Archaeologists take pigs very seriously.”

Pigs & Ancient Rome

Whether or not pigs were eaten in some parts of Biblical Israel, there is no doubt that not eating pork became synonymous with Jewish practice. In Rome, things were different. There, eating pork was widespread and enjoyed, and it was one of the most common meats associated with its residents. And as Jordan Rosenblum points out in his 2010 paper Why Do You Refuse to Eat Pork?’’ Jews, Food, and Identity in Roman Palestine swine were one of the four most common animals used for sacrifices in Rome. It was used in the most sacred rite of the Roman religion known as the suovetaurilia, in which a pig, a sheep and a goat were sacrificed to Mars, as part of a ceremony consecrating the land to the gods. According to the Roman philosopher Epictetus “the conflict between Jews and Syrians and Egyptians and Romans, [was] not over the question whether holiness should be put before everything else and should be pursued in all circumstances, but whether the particular act of eating swine’s flesh is holy or unholy.”

So pigs turn out to have played more of a role in our history than would be expected. In biblical times, eating pork may have been a marker of whether you came from Israel or Judea.

“Whereas the pentateuchal prohibition against eating pork (Lev 11:7; Deut 11:8) has garnered copious scholarly attention, the proscription against eating finless and scaleless aquatic species that appears in the verses immediately afterward (Lev 11:9–12; Deut 14:9–10) has merited significantly less consideration. ”

From Swine To catfish

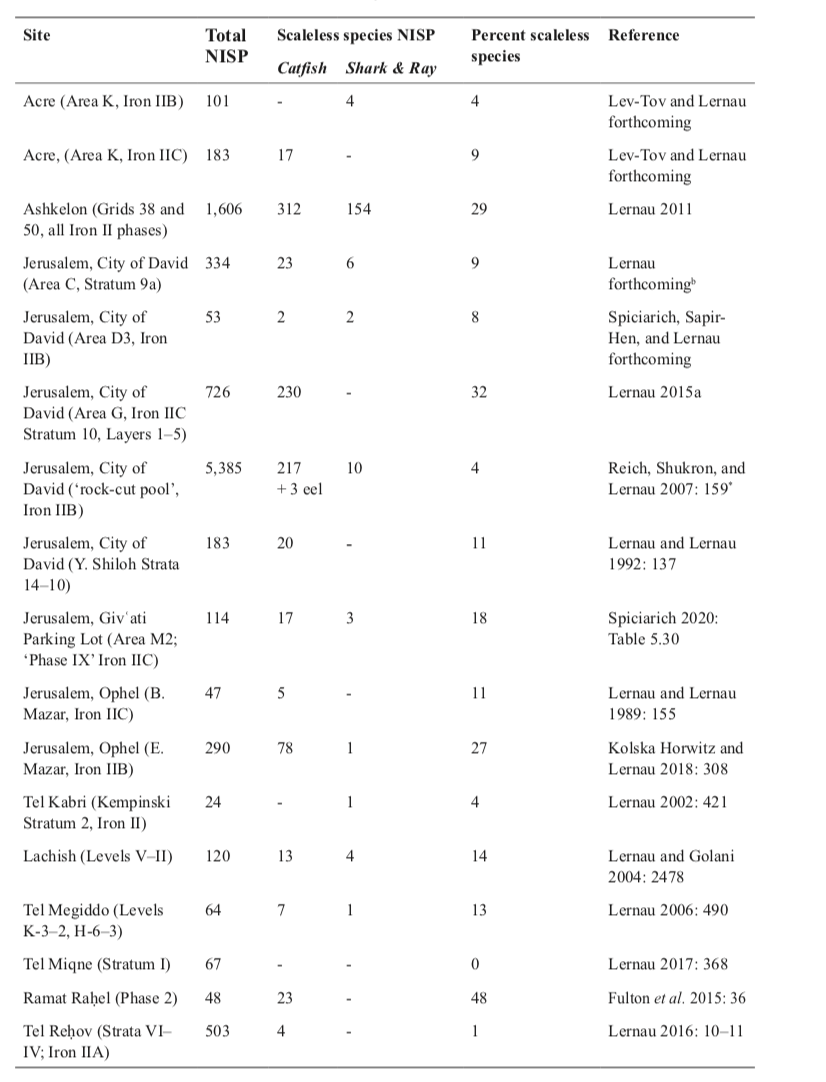

Very recently two Israeli archeologists took a look at the prohibition that is listed in the Bible immediately following the ban on all things porcine. “The earliest textual reference to a proscription against the consumption of aquatic species that lack fins or scales is found in a set of passages repeated twice in the Pentateuch, in both instances immediately following a prohibition against the consumption of pork” they wrote in a paper that garnered some attention. The two analyzed the makeup of fish remains at 30 sites throughout the southern Levant from the Late Bronze Age through to the end of the Byzantine period (ca. 1550 BCE to 640 CE). They found that “the consumption of scaleless fish— especially catfish—was not uncommon at Judean sites throughout the Iron Age and Persian periods.” Here for example is their analysis of seventeen sites from the Iron Age II period (ca. 950–586 BCE), “during which inhabitants of the highlands coalesced politically into the two kingdoms of Israel and Judah.”

Table of fish species found in Iron Age II period settlements in Israel. From Yonatan Adler & Omri Lernau (2021) The Pentateuchal Dietary Proscription against Finless and Scaleless Aquatic Species in Light of Ancient Fish Remains, Tel Aviv, 48:1, 5-26.

The archeologists believed they had uncovered an important finding: Biblical Jews ate catfish.

At over three-quarters of the sites with available evidence, scaleless fish remains are present in modest to moderate amounts: 13% on average (excluding outliers below 5% and above 30%). Significantly, all the fish assemblages from sites within the Southern Kingdom—first and foremost Jerusalem— presented evidence of modest to (more often) moderate amounts of scaleless fish remains. While more limited data is available to-date from sites associated with the Northern Kingdom, there is little reason to think that scaleless fish were consumed to a lesser degree there than in Judah (the assemblage from Iron IIA loci at Tel Reḥov notwithstanding). From the time following the end of the Iron II, three assemblages from layers postdating 586 BCE in Jerusalem contain remains that suggest that consumption of catfish in Jerusalem continued into the Persian period.

In a Times of Israel podcast one of the authors of the paper, Ariel University’s Dr. Yonatan Adler had this to say: “We do not have any evidence that the Judean masses prior to the middle of the second century BCE had any knowledge of the Torah or observed the rules of the Torah.” And that proved just a bit much for Drs. Joshua Berman and Ari Zivotovsky of Bar Ilan University who responded in another piece published in The Times of Israel just two weeks ago. “We believe that these assertions are not supported by the evidence and that the media portrayal of this study as “a scoop” is unwarranted” they wrote.

Not so fast- there is something fishy going on here

First, they point out that lots and lots (and lots) of things proscribed in the Bible were ignored by the ancient Israelites.

We know from the Bible’s own testimony that although intermarriage is proscribed by the Torah, intermarriage was rampant during the period of Ezra and Nehemiah. And although the Torah proscribes idol worship, the prophets censure Israel for doing just this, and indeed we find many dozens of figurines in Israelite sites during that time, including locations near where some of these non-kosher fishbones were found. Not dozens, but hundreds of chapters of the Bible chronicle Israel’s failure to observe the words of the covenant with God.

Next, they are critical of the conclusion that “all the fish assemblages from Judah available for analysis contained significant numbers of scaleless fish remains, especially catfish.” That’s not true, from the very evidence contained in the study by Adler. Most of the fish remains are from kosher fish.

This is one of seventeen sites they survey for this period, but with 5,385 fishbones, it contains far more bones than all other sites from this period combined, and triple the number of bones of all other Jerusalem sites combined, and is thus of great significance. Remarkably, 96% of the fish remains here are from kosher fish. Other sites in the City of David have a much higher percentage of non-kosher fishbones. Remarkably, again, these other sites date from the period just prior to the destruction of Jerusalem, broadly a period in which the residents of Judah come in for particularly harsh censure by the prophets of Israel.

It is the prophet of that period, Isaiah who castigated Israel for eating “the swine’s flesh, the abominable things (sheketz) and the mouse” (Isa 66:17).

This passage from Isaiah likewise undermines Adler’s claim that “We do not have any evidence that the Judean masses prior to the middle of the second century BCE had any knowledge of the Torah or observed the rules of the Torah.” The author of this verse in Isaiah describes a reality whereby part of the community is abiding by the dietary standards of Leviticus 11 and part of it is not. Jews in his day may not have recognized his deliberate references to the Torah text of the dietary laws, just as many Jews today – observant or not – are familiar with these laws yet while unfamiliar with the actual words of the verse. But the account of the prophet’s censure in Isaiah 66 has coherence only if there are a group of Jews observing these laws and another group violating them. The prophetic books offer us a vivid window into the social reality of ancient Israel, and it would, here too, require special pleading to maintain that the social reality portrayed in Isaiah 66 is fiction through and through.

Some Jews were eating kosher fish and others were not. That was the reality that Isaiah was rallying against. It was a reality in which the rules of the Torah may have been ignored, but at least the rules were known. Adler and Lernau claimed that “the ban against finless and scaleless aquatic species apparently deviated from longstanding Judean dietary habits,” whereas Berman and Zivotovsky believe that “faunal finds of fishbones – kosher and non-kosher – in ancient Israel reveal a checkered observance of the Torah’s dietary laws that broadly hews to what the Bible itself.” We will no doubt hear more of this interesting academic debate in the future, especially since Adler will be publishing a book next year called The Origins of Judaism: An Archaeological-Historical Reappraisal. But Adler’s findings, and those of other archaeologists support the contention in today’s page of Talmud that when it comes to keeping kosher, Jews have always had an appetite for the forbidden.

From here.