Who could forget that classic scene from The Life of Brian, in which the Judean rebels ask, “What have the Romans ever done for us?”

After much debate, Reg, the rebel leader (played of course by the brilliant John Cleese) concludes “All right, but apart from the sanitation, the medicine, education, wine, public order, irrigation, roads, a fresh water system, and public health, what have the Romans ever done for us?”

We might have asked the same thing about the Maccabees, or as they are known in Hebrew, the Maccabim (spelled either מַכַּבִּים, or מַקַבִּים), the heroes of the story of Chanukah. They gave us Chanukah to be sure, and their name: Maccabi Games and Maccabi Tel Aviv Football Club,and Maccabi Haifa and Maccabi Petach Tikvah, and more. But really, aside from a stunning military victory, a few decades of peace, freedom to worship in the Temple, and some naming opportunities, what have the Maccabim ever done for us? Actually, a lot more than you might have thought. They might have given us everything.

CHANUKAH in a nutshell

As a reminder, Antiochus had set his sights on conquering Alexandria in Egypt but was prevented from doing so by the Romans, who ordered him to withdraw or consider himself to be at war with the Roman Republic. Recognizing when he was defeated, he turned his army north. According to the Second Book of Maccabees (5:11–14), here is what happened next:

Raging like a wild animal, [Antiochus] set out from Egypt and took Jerusalem by storm. He ordered his soldiers to cut down without mercy those whom they met and to slay those who took refuge in their houses. There was a massacre of young and old, a killing of women and children, a slaughter of virgins and infants. In the space of three days, eighty thousand were lost, forty thousand meeting a violent death, and the same number being sold into slavery.

As described by the Jewish historian Josephus (who was not an eyewitness, but lived about a century later), here is what caused the Jewish revolt:

Now Antiochus was not satisfied either with his unexpected taking the city (Jerusalem), or with its pillage, or with the great slaughter he had made there; but being overcome with his violent passions, and remembering what he had suffered during the siege, he compelled the Jews to dissolve the laws of their country, and to keep their infants uncircumcised, and to sacrifice swine's flesh upon the altar; against which they all opposed themselves, and the most approved among them were put to death.

The Maccabim, led by Mattathias (Mattisyahu) and his five sons, waged a guerilla campaign against their Greek oppressors, which culminated in a military victory and the re-dedication of the Temple in Jerusalem. Of course there may have been a miracle, something to do with oil (though the Rambam makes no mention of it, as we have discussed elsewhere), but the real miracle was the restoration of an independent Jewish state under the Hasmoneans, until civil war and an intervention by the Romans ended it all in 63 BCE.

By any account this would be enough for which to thank the Maccabim (well, not the civil war, but certainly the rest). But it turns out that perhaps we owe the Maccabim a great deal more than this.

a search for the terminus ante quem

In 2022, the Israeli archeologist Jonathan Adler published The Origins of Judaism, in which he asked a simple question: what is the earliest archeological evidence for Jewish practice? Adler was not primarily interested in textual evidence (though he cites a fair amount), but with the lived experience of individuals, on their practice and not on their beliefs. Adler focussed on epigraphic and archeological discoveries, to arrive at a terminus ante quem, “the boundary of time when or before which the particular element of Judaism under examination must have first emerged.”

…the date of the earliest available evidence demonstrating that Judeans knew something resembling the Torah and were observing its laws will serve as the terminus ante quem for the earliest emergence of Judaism. That it to say, Judaism must have emerged at this time or earlier. Lacking further evidence, this is the most we can determine with any degree of confidence (18).

I know what you are thinking, and Adler addresses it:

Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. It is possible, for example, that the Judeans commonly knew of the Torah and were observing its laws for decades or even centuries prior to our established terminus ante quem, and that for whatever reasons no evidence has survived (ibid).

Adler’s conclusion, based on a “data-driven analysis” is that “we possess no compelling evidence dating to any time prior to the middle of the second century BCE which suggests that the Judean masses knew of the Torah and were observing its laws in practice. This will establish the middle of the second century BCE as the overarching terminus ante quem for the initial emergence of Judaism.” Which is to say, the Hasmonean period. Here is just some of that data.

Kashrut

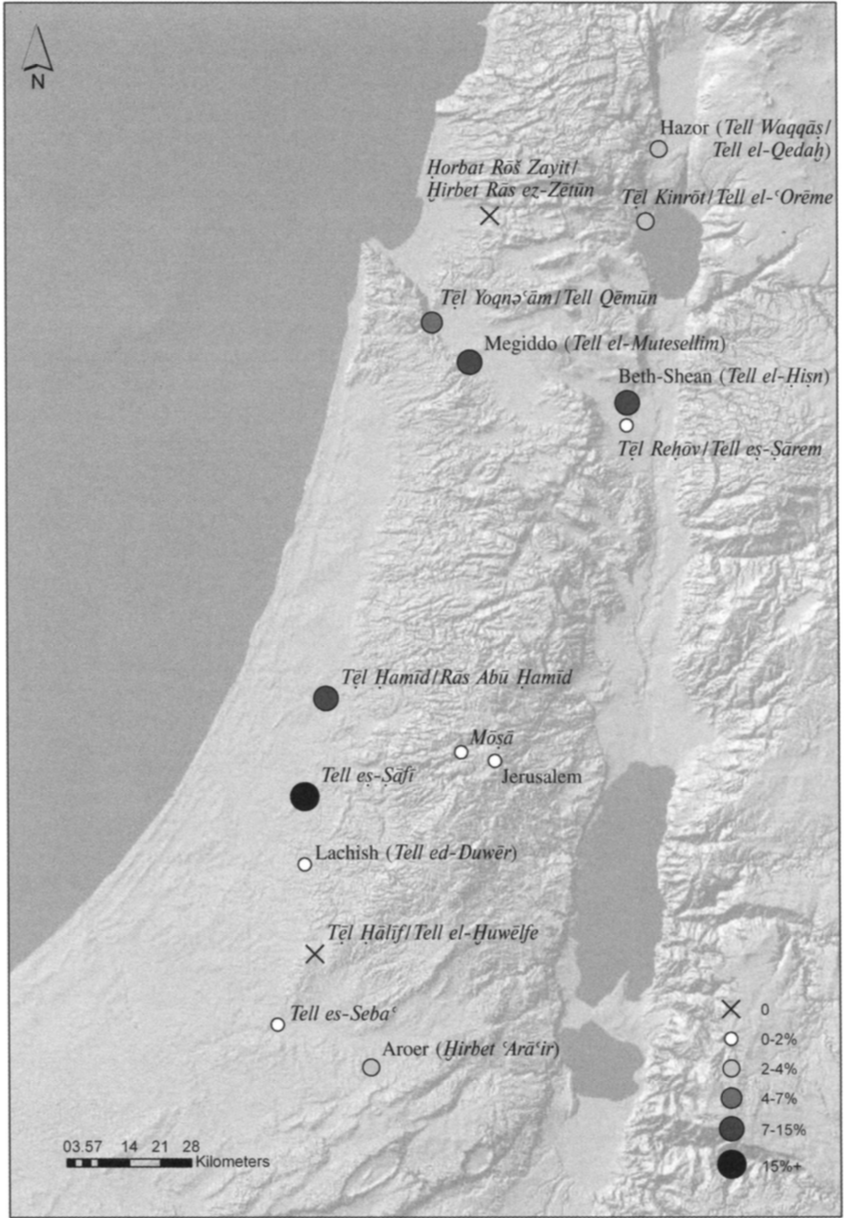

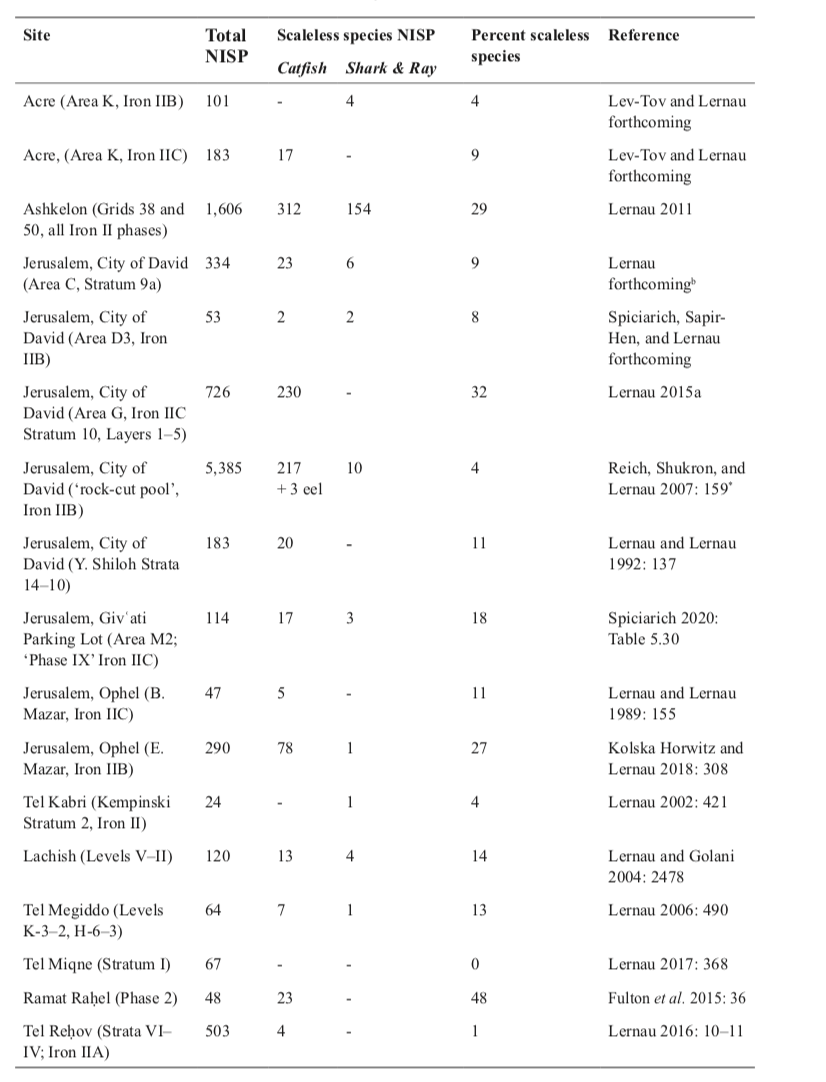

As we have discussed elsewhere on Talmudology, Adler analyzed the makeup of fish remains at 30 sites throughout the southern Levant from the Late Bronze Age through to the end of the Byzantine period (ca. 1550 BCE to 640 CE). They found that “the consumption of scaleless fish— especially catfish—was not uncommon at Judean sites throughout the Iron Age and Persian periods.” In other words, Judeans likely ate catfish, which are not kosher. [You can read a criticism of this claim from Bar Ilan’s Joshua Berman and Ari Zivotovsky here.] Pig remains suggest that by the Roman era, Judeans were not eating pork. “But here the trail of evidence ends. Prior to the second century BCE, there exists no surviving evidence, whether textual or archeological, which suggests that Judeans adhered to a set of food prohibitions or to a body of dietary restrictions of any kind…it is only from the Hasmonean period onward that we may claim to know of Judeans adhering to a set of dietary restrictions of any kind.” (49)

Ritual Purity

Josephus describes two stories set in the second half of the first century BCE that relate to ritual purity. The Dead Sea Scrolls, composed some time in the second or first century BCE are of course full of laws that address this area. And they are mentioned in the Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha, dated to a similar time. The Maccabim themselves are described (2 Mac 12:38) as having purified themselves “according to the custom” before making camp for Shabbat. Beyond this, the Hebrew Bible provides “little evidence” that the laws of tumah and tahara were known before the second century BCE. For example, although the complex rituals around purification after touching a corpse (tuma’at met) or contracting a skin disease (tzara’at) are mentioned in the Torah, there is not “even one passing allusion to anyone putting these rites into practice elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible.” In addition, although there are many mikva’ot (ritual immersion pools) that date to the Hasmonean period, no stepped mikva’ot have yet been dated “to any time earlier than the late second century BCE” (82).

Visual Art

There is a Torah ban on making a graven image, but the earliest imageless coins were minted in Judea in 131 BCE. In contrast, all the surviving coins minted in Judea in the fourth century BCE display human and animal images. The Persian era Judean authorities included figural images on all their minted coins and exhibited “no signs of regard for any such Pentateuchal prohibition.” Adler suggests that it was only from the Hasmonean era onward “that there is a never before seen aversion to figural art among Judeans” (111).

Tefillin and Mezuzah

We have yet to unearth any tefillin and mezuzot artefacts that predate the second century BCE, though, to be fair, these objects are made of perishable organic material. (Remember, Adler is focussed on the lived experience of the Judeans, not what may have been written in the Torah. The latter certainly predates this.) Fun fact: perhaps the oldest archaeological witness to tefillin or mezuzah is the Nash Papyrus, dated to mid-second century to the mid-first century BCE. But there are many finds that demonstrate that by the first century CE tefillin and mezuzah existed as Judean ritual practices.

The Menorah

“A single golden, seven-branched menorah as prescribed in the Pentateuch certainly stood in the temple prior to its destruction in 70 CE, and both texts and archaeological finds suggest that Judeans living in both the first century CE and the first century BCE were well aware of both its existence and its general appearance. Prior to the mid-first century BCE , not a single example has been found of a seven branched menorah depicted in Judean (or Israelite) art, and earlier texts that speak of either a single or multiple golden or silver lampstands in the temple provide little correspondence with Pentateuchal prescriptions” (167).

Menorot in Judean art only appear from the Hasmonean time onward. From here.

Judaism as a way of Life emerged during the Hasmonean Period

Adler provides more evidence, from the observance of Shabbat and Yom Kippur and Sukkot, to the establishment of the synagogue. You will have to read that for yourself, or listen to a talk in which he outlines his thesis.

Our resolute conclusion has been that some point around the middle of the second century [BCE] should be regarded as our terminus ante quem, the time during or before which we ought to seek the emergence of Judaism….we would be remiss not to regard as at least suggestive the fact that all of the many practices and prohibitions analyzed throughout this book first come into historical focus precisely during the course of the Hasmonean period. Is it possible that Judaism as a way of life followed by Judeans at large first emerged only around this time?

It turns out that the Maccabim have done a lot for us. Way more than you might have once thought. They either (i) left us with the earliest cultural artefacts that belong to a Judaism we might recognize as our own, or (ii) were the first to practice it. Either way,

…it would not be wrong to view Judaism as having emerged out of the crucible of Hellenism, which dominated the cultural landscape of the time. In a poetic way, it seems only fitting that our English word “Judaism” itself is the result of a Hebrew/Greek hybrid, rooted etymologically in the Greek rendering of the Hebrew “yehudayah” merged with the Greek suffix'“-ismos”. (236)

Now that is a something worth saying Hallel for.

אחינו כל בית ישראל

הנתונים בצרה, בצרה ובשביה

העומדים בין בים ובין ביבשה

המקום ירחם ירחם עליהם

ויוציאם מצרה לרווחה

ומאפלה לאורה ומשיעבוד לגאולה

השתא בעגלא ובזמן קריב

ואמרו אמן