Today the Daf Yomi cycle embarks on a study of the laws of marriage, as it begins the first page of Kiddushin. As we have noted before, marriage in talmudic times had very little to do with love. And by very little I mean nothing. Within the tractate of Kiddushin, love, (or one of its conjugates) appears twenty-four times. Yet in only one instance is it in the context of spousal love - (and that is a quote from משלי 9:9). This was not a result of talmudic law, but rather a reflection of the institution of marriage across all cultures for about five thousand years.

A (REALLY BRIEF) HISTORY OF THE INSTITUTION OF MARRIAGE

The historian Stephanie Coontz noted that for most of history, marriage was not primarily about individual needs. Instead it was about "getting good in-laws and increasing ones's family labor force." In ancient Roman society "something akin to marriage was essential for the survival of any commoner who was not a slave...A woman needed a man to do the plowing. A man needed a woman to spin wool or flax, preserve food, weave blankets and grind grain, a hugely labor-intensive task." Marriage was essential to survive. So it comes as no surprise that historically, love in marriage was seen as a bonus, not as a necessity. In many societies (including that described in the Talmud), a woman's body was the property first of their fathers, and then of their husbands. A woman had to follow, as Confucious put it, the rule of three obediences: "while at home she obeys her father, after marriage she obeys her husband, after he dies she obeys her son."

This pattern existed for centuries. Here's a rather graphic, but certainly not isolated example. In the 1440s in England, Elizabeth Paston, the twenty-year old daughter of minor gentry, was told by her parents that she was to marry a man thirty years her senior. Oh, and he was disfigured by smallpox. When she refused, she was beaten "once in the week, or twice and her head broken in two or three places." This persuasive technique worked, and reflected a theme in Great Britain, where Lord Chief Baron Matthew Hale declared in 1662 that "by the law of God, of nature or of reason and by the Common Law, the will of the wife is subject to the will of the husband." Things weren't any better in the New Colonies, as Ann Little points out (in a gloriously titled article "Shee would Bump his Mouldy Britch; Authority, Masculinity and the Harried Husbands of New Haven Colony 1638-1670.) The governor of the New Haven Colony was found guilty of "not pressing ye rule upon his wife."

It is with this historical perspective that the attitudes of the rabbis in Kiddushin (and in the Talmud in general) should be judged. Marriage was an economic arrangement, and so it required economic regulation. Here's just one example we have previously noted (and there are dozens): the Mishnah in Ketubot ruled that a widow may sell her late husband's property in order to collect the money owed to her in the ketubah without obtaining the permission of the court. This leniency was enacted, (according to Ulla) "משום חינה" - so that women will view men more favorably when they understand that the ketubah payment does not require the trouble of going to court. Consequently (and as Rashi explains) women will be more inclined to marry. Which leaves the reader to wonder just for whom this law was really enacted.

“...the older system of marrying for political and economic advantage remained the norm until the eigthteenth century, five thousand years after we first encountered it in the early kingdoms and empires of the Middle East.”

The Changing Face of Marriage

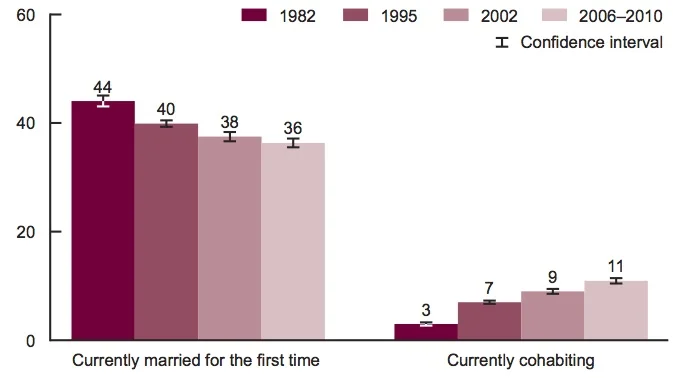

According to the US Census Bureau, married couples made up 70% of all households in the US in 1970. In 2012 they accounted for less than 50%. As the prevalence of married couple declined, that of cohabiting (ie. non-married couples) has increased. A CDC survey found that 48% of women interviewed in 2006-2010 cohabited as a first union, compared in only 34% in 1995. Of those who cohabit, about half of the unions result in marriage, and a third dissolve within five years.

Current marital and cohabiting status among women under 44 years of age, United States: 1982, 1995, 2002, and 2006–2010. From Copen C. et al. First Marriages in the United States: Data From the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National Health Statistics Report 49. March 2012.

Not surprisingly, cohabiting partners are also increasing likely to be the site for childrearing. In 2002 about 15% of children were born to cohabiting parents; by 2011 this had risen to over 25%. In January, a review in The Economist noted that the rate of children born to unmarried parents ("out of wedlock") averages 39% in western countries - a five-fold increase since 1970.

Policymakers wish they could change the trend. Unmarried parents are more likely to split up. Their children learn less in school and are more likely to be unhealthy or behave badly. It is hard to say how much of this difference is due to marriage itself, however, because unmarried parents differ a great deal from married ones. They are poorer, less well-educated and more likely to be teenagers, for example. (The Economist, Love and Marriage, Jan 14, 2016)

From The Ecomonist, based on OECD data.

The discussion of marriage in the Talmud revolves around its contractual arrangements. But for most Jews today, the concept of marriage revolves around love. Economics have nothing to do with it. Western society has changed its beliefs about the nature of marriage, and so have we. Still not convinced? Then answer this. Did your parents marry for love or money? If you are married - did you marry for love or for economic advancement (and how did that work out)? If you are not married, but want to be, what is driving you? The search for the love of your life, or the search for physical security? And if you have children - or grandchildren, would you want them to marry because they loved their significant other, or because it would be a good way to unite two families and insure financial stability? If your answers were like mine, they were closer to contemporary secular values about marriage than they were to the models of marriages described in the Talmud. And that's probably a very good thing.