אמר ריש לקיש: טב למיתב טן דו מלמיתב ארמלו

Resh Lakish said: It is better for a woman to live as tad du than to live alone...

In a 1975 lecture to the Rabbinical Council of America, Rabbi J.B. ("the Rav") Soloveitchik, quoted the aphorism of Resh Lakish found in today's page of Talmud. The Rav went on to explain that it was "based not upon sociological factors...[but] is a metaphysical curse rooted in the feminine personality. This is not a psychological fact; it is an existential fact." Wow. Is this statement of Resh Lakish really an existential fact? To answer this, we need to first answer another question - what do his words actually mean?

One way to understand the aphorism is as follows: "A widow would rather live in misery than live alone." But that's not the only translation, which depends on the exact meaning of the Aramaic phrase טן דו (tan du). There are a number of possibilities.

Rashi

Let's start with Rashi and his explanation to our text:

בגופים שנים בעל ואשתו ואפילו אינו לה אלא לצוות בעלמא

Tan Du: Two bodies. A husband and wife; even if he is nothing more to her than company.

This explanation of Rashi's does not suggest that married misery is preferred over a single life. This is a slightly different explanation that Rashi gave in when we met this phrase in Yevamot.

טן דו - גוף שנים. משל הדיוט הוא, שהנשים אומרות טוב לשבת עם גוף שנים משבת אלמנה

Tan Du: Two bodies. This is a common maxim, for women say that it is better to live as two than to live alone.

So according to Rashi in both Yevamot and here in Kiddushin, Resh Lakish never addresses living in misery. He just made the observation that women prefer marriage over a single life.

JASTROW'S DICTIONARY

Not so Marcus Jastrow, whose dictionary (published 1886-1903) became a classic reference text for students of the Talmud. Jastrow translated טן דו as a load of grief, an unhappy married life. This will become very important later, so make note.

THE SONCINO TRANSLATION

Moving on, the Soncino translation of Kiddushin (first published in 1966) echoes Jastrow's translation: "It is better to carry on living with trouble than to dwell in widowhood". This is similar to the Soncino translation of the same phrase when found in Yevamot 118: "It is preferable to live in grief than to dwell in widowhood." However, a footnote to the text in Yevamot notes that "Levy compares it with the Pers., tandu, two persons." (The reference here is to Jacob Levy's German Dictionary Chaldisches Worterbuch uber die Targumim - Aramic Dictionary of the Targums and a Large Part of Rabbinic Literature.) Why did Isidore Epstein, editor of the Soncino Talmud, choose to use Jastrow's translation over that of Levy - and that of Rashi? Answering that will take us too far off track, so we will leave it for another time...

MELAMED'S ARAMAIC-HEBREW-ENGLISH DICTIONARY

Melamed's Aramaic-Hebrew-English Dictionary (Feldheim: Jerusalem 2005) follows Rashi : "טן דו = two bodies."

THE ARTSCROLL TRANSLATION

The ArtScroll Schottenstein Talmud basis its translation on Rashi: "It is better to live as two together than to live alone." However a footnote (note 18) brings its meaning closer to that of Jastrow and the Soncino: "I.e it is better to be married - even to a husband of mediocre stature - than to remain single."

THE KOREN STEINSALTZ TRANSLATION

In his Hebrew translation of the Aramaic text found in Yevamot 118, Rabbi Steinsaltz follows Rashi, and translates טן דו as "two bodies." A side note points out that the true origin of the phrase is not known, though it likely comes from Persian.

The newer English Koren Talmud follows the same translation: "It is better to sit as two bodies, ie., to be married, than to sit alone like as a widow. A woman prefers the any type of husband to being alone." Elsewhere in the Koren series, (Yevamot 118a) there is a note, (written by Dr. Shai Secunda), which is more definitive than the Hebrew note. Tan Du is from middle Persian, meaning together. It's nothing to do with being miserable.

TESHUVOT HAGE'ONIM

I've left perhaps the strongest textual witness for last: how the words Tan Du were understood during the period of the Geonim (c. 589-1038). In 1887 Avraham Harkavy published a collection of responsa from this period that he found in manuscripts held in the great library of St. Petersburg. In this collection is a reference to our mysterious words:

טן דו בלשון פרסי שני בני אדם. ארמלו יחידות

טן דו in Persian means two people. ארמלו means alone.

Chronologically, this is our earliest source, and, therefore, perhaps our most compelling. Case closed.

VARIATIONS OF THE RESH LAKISH RULE

So far we have the following four versions of what we will now call the Resh Lakish Rule:

It's better for a woman to be...

....married and unhappy than single (Jastrow)

...in a less desirable or mediocre marriage than no marriage at all (ArtScroll footnote).

...miserable and married than to be a widow (Soncino).

...with a husband than to be alone (ArtScroll, Koren, Melamed, Rashi, Teshuvot Hage'onim)

WHAT IF TAN DU MEANS MISERABLE?

It seems that the translation of טן דו as miserable originated with Jastrow, and that those who translate Resh Lakish as saying "misery is better than being single" are following in the Jastrow tradition. If we were to evaluate the Resh Lakish Rule per Jastrow (and Soncino and an ArtScroll footnote), the question is, what, precisely, constitutes a "miserable marriage"? One in which the woman feels physically safe but emotionally alone? One in which her husband loves her dearly but is unable to provide for her financially? Or one in which she has all the money she needs but her husband is an alcoholic? Tolstoy has taught us that each unhappy family (and presumably each miserable marriage) is unhappy in its own unique way. The point here is not to rank which is worse.

“[In the 1950s, a] bad marriage was usually a better option for a woman, especially if she had a child, than no marriage at all.”

Today it would be utterly silly (and incredibly rude and insulting) to suggest that a woman is better off miserable than single. But after our review, that does not appear to be what Resh Lakish ever said. What he really said was this: a woman would be better off (טב) married than living alone (as a widow). Resh Lakish didn't explain what he meant by better off, so we will have to assume that what he meant was a measure of overall well-being, or what we call... happiness. What we want to know, is how this understanding of Resh Lakish stands up today. Was Rabbi Soloveitchik correct when he called this "an existential fact"?

MEASURING HAPPINESS & HAPPINESS INEQUALITY

Happiness inequality exists and has been well documented. University of Pennsylvania economists Betsy Stevenson and Justin Wolfers, (who live together, but not within the bonds of marriage), note that

“...the rich are typically happier than the poor; the educated are happier than those with less education; whites are happier than blacks; those who are married are happier than those who are not; and women—at least historically—have been happier than men.”

But why is this so? Don't we all oscillate around a set point of happiness, regardless of what life may throw at us? Some psychologists think so.

LOTTERY WINNERS & ACCIDENT VICTIMS: THE SET POINT THEORY OF HAPPINESS

According to the set point theory of happiness, we all revolve around our own, innate happiness point. When we are faced with adversity, we do, to be sure, become sadder. But we eventually bounce back to where we were before, back at our set point. Similarly, when met with some good mazal, we are, for a period, more happy. But then we return to our innate set point for happiness, wherever that was prior to the good fortune. The evidence for this comes from a classic study which found that "lottery winners were not much happier than controls" and that accident victims who were paralyzed "did not appear nearly as unhappy as might have been expected." (The problem is that this study used a tiny sample - there were only 22 lottery winners and 29 paralyzed accident victims - so we need to be very cautious in generalizing from it.)

Married people are – on average – happier than those who are single, but perhaps this fact does not suggest causation. Some would argue that it's just a correlation. A grumpy person, unable to hold down a job and miserable to be around, is not likely to find another individual willing to marry him. So it’s not that marriage makes you happier –it’s that happier people are more likely to find a partner and get married. According to this set point theory of happiness, the Resh Lakish Rule would not be supported, since the act of marrying would have no overall long-term effect on happiness.

THE MORE IS BETTER THEORY OF HAPPINESS

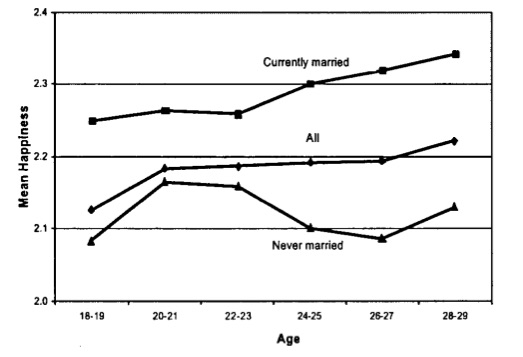

However, evidence from a 15 year longitudinal study of 24,000 people suggests that "marital transitions can be associated with long-lasting changes in satisfaction." This would support the claim that marriage is causally related to happiness. It's not that you went from being a happy person who was once single to being a similarly happy person who is now married. What actually happened was that the marriage had an effect on just how happy you became. And data from other large cohort studies show that happiness increases when people marry. Just look at the happiness of women by marital status in the figure below. Was Resh Lakish onto something?

Mean happiness of women by marital status, birth cohort of 1953-1972, from ages 18-19 and 28-29. From Easterlin, RA. Explaining Happiness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2003. 100 (19): 11176-11183.

All this supports the Resh Lakish Rule that people are happier when they are married. (I say people because all the evidence applies equally to men too.) But we can get even more specific, because Resh Lakish used the word ארמלא, which most likely means widowed (and hence has a secondary meaning of being alone). There is actually data that applies to this more specific Resh Lakish claim about widows, and it comes from The Roper Center at the University of Connecticut.

From Economics and Happiness, ed Bruni L. Oxford University Press 2005.

As shown in the table, 62% of women who are widowed want to be happily married. (Of course this also means that about 40% of widowed women would rather not be married - even happily. That’s a huge proportion. Still, the overall finding still supports the Resh Lakish Rule.) The women's perspective is the most important perspective in this conversation, and when women (widows) were asked, most wanted to be married again. Widows indeed wish to live as two rather than live alone. I don't think this amounts to anything like an existential fact, as claimed by the Rav. But the evidence from the social sciences would certainly support the Resh Lakish Rule.