The Palestinian Viper צפע ארצישראלי. Vipera palaestinae

Snake Bites Everywhere

Snake bites were a widespread fear in ancient Israel. The Talmud warns that snakes can be found in houses and records a snake attack that occurred in the toilet, so going to the bathroom was a risk to one’s life. (Snakes still appear to make relieving oneself in the Holy Land a dangerous enterprise, if this report is to be believed.) There was also a great fear of drinking water into which a snake may have expelled some venom, and loyal Talmudology readers may recall that we previously examined this concern (and included a clip of a man safely drinking freshly expelled snake venom. Actually, if you remember, there is no danger, even in places where snakes are found. Snakes only discharge their venom when they intend to bite, not when stopping for a drink. And even if there was venom in the liquid, snake venom is not absorbed by the human gastrointestinal tract, so it would have absolutely no effect. But I digress.)

In tomorrow’s page of Talmud, the fear of snakes is taken to a whole new level, at least for women. What should a woman do if she thinks she is being being pursued by a particularly amorous snake? How can she get that snake to give up the chase? And finally, what can she do if the snake has already entered her is an act of carnal intimacy?

All this shows how dangerous snakes were, and so when they did not bite, it was considered to be miraculous. Hence the Mishnah (Avot 5:5) records that one of the ten miracles that occurred during the time of the Second Temple was that no person was ever injured by a snake.

In today’s page of Talmud, we focus on a cure for a snakebite:

האי מאן דטרקיה חיויא ליתי עוברא דחמרא חיורתא וליקרעיה ולותביה עילויה והני מילי דלא אישתכח טרפה ההוא

One who was bitten by a snake should have the fetus of a white donkey brought to him, and it should be torn open and placed on the snakebite.

At first the suggestion sounds ridiculous. Why on earth should a donkey’s fetus cure a snakebite, and what difference does the color of the mother donkey make? But we can begin to make sense of the suggestion by noting the Aramaic words for snake (chivyah) and white (chivrah). Say them out loud. There was a belief that “like cures like” and while we are still at a loss to describe why a donkey’s fetus might be used, we can at least make sense of the white aspect of the whole thing.

snake bites in Israel and around the world

The Talmudic concern for snakebites clearly reflected a reality: they are prevalent in the middle east, and were often deadly. Indeed snakebites remain a threat in Israel and beyond (though in my six years of working in Jerusalem as an emergency physician I recall treating only one victim; he was a handler at a private snake collection- who should have known better.)

In the US, venomous snakes are found in every state except Maine, Alaska and Hawaii, and each year in the US there are about 2,000 recorded venomous snakebites that result in about 6 deaths. The World Health Organization estimates that snakes kill between 20,000 and 94,000 people per year.

Kastururante A. et al. The Global Burden of Snakebite. PLOS Medicine 2008. 5:1591-1604

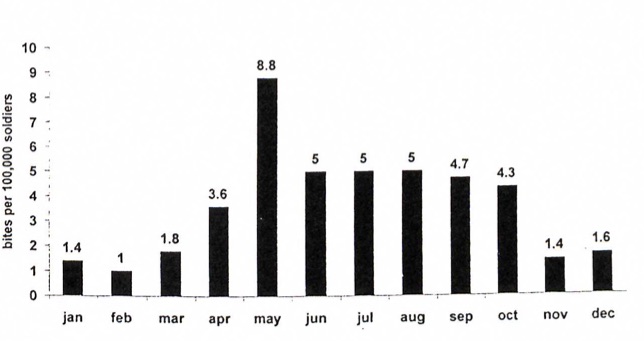

Snakes are such a problem for Israel and its neighbors that in 1998 the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and the Jordanian Armed Forces held a joint conference on the topic. Since snakes are cold blooded, they are virtually inactive in the winter months, and summer time can be too hot for them; hence they are most active in the spring and fall. Just as the Talmud described in Yevamot 116b, the IDF found that the peak incidence for snakebites is May (that is, harvest time).

Snakebites in the IDF. Average incidence per month, 1993-1997. From Haviv, J, et al. Field treatment of snakebites in the Israel Defense Forces. Public Health Rev 1988; 26:24-256.

There are at least eight species of poisonous snake found in Israel, of which the most common is the Palestine Viper, (shown in the photo at the top of the page) which is found in all regions north of Be’er Sheva. It is this snake that is responsible for all the fatal snake bites in Israel, though the IDF reported not one fatality during its five year study period.

sidebar: palestinian or israel viper?

Let's re-read that last paragraph:

“There are at least eight other species of poisonous snake found in Israel, of which the most common is the Palestine Viper”

Is that its real name? Well, it depends who you ask, or perhaps, in what language you ask. The snake's Latin name is Vipera palaestinae, and its Hebrew name is...צפע ארצישראלי! The snake could have been given a Hebrew name that was transliterated from the Latin, i.e. צפע פלסטיני – but that's not what whoever chose the name decided to do. Outside the case of the viper in the Jerusalem Zoo, this multiple naming is evident:

(It's not only snakes that have may have a crisis of identity. The chamomile flower, common in Israel, is called by its scientific name Anthemis palaestina, and in Hebrew it is קחוון ארצישראלי. Similarly the Terebinth; it is known to the scientific community as Pistacia palaestina, and in Hebrew as אלה ארץ-ישראלית. I could go on, but the point is made.)

One snake living happily, called two names by two peoples. There's a lesson there somewhere. But I digress.

the treatment of snake bites in the Talmud - and today

As we noted, today’s page of Talmud offers a remedy for the unfortunate person bitten by a snake (of either the Palestinian or Israeli variety. Not the person. The snake.)

If one is bitten by a snake, he should take an embryo of a white donkey, tear it open, and place it on the bite

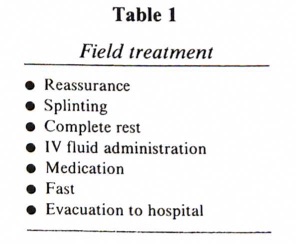

How does this advice compare with the IDF field manual? Not very well, as you can see from this list of the field treatment do's and dont's from the Medical Corps of the IDF. Embryos of white donkeys do not make it. (Donkey embryos as a therapy also fail to make a fascinating 1953 report of 65 cases of viper bite in Israel.)

Haviv, J, et al. Field treatment of snakebites in the Israel Defense Forces. Public Health Rev 1988; 26:24-256.

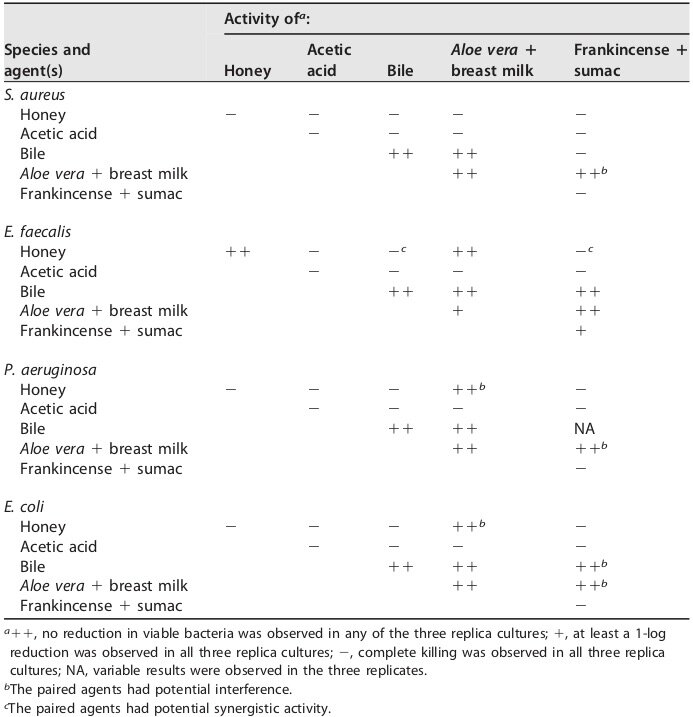

Snake venom produces its deadly effects by causing a coagulopathy, which is the general name for a breakdown in the normal way the blood clots. When things get really bad, snake venom causes a consumption coagulopathy, in which (as its name implies), all the vital bits that are needed for blood to clot are consumed, leaving the poor victim susceptible to life-threatening uncontrollable bleeding. Here's a chart of the clotting pathways that medical students have to learn (a process only slightly less painful than a snake bite itself,) with the bits that venom attacks shown in green.

Diagram of the clotting pathway showing the major clotting factors (blue) and their role in the activation of the pathway and clot formation. The four major groups of snake toxins that activated the clotting pathway are in green and the intermediate or incomplete products they form are indicated in dark red. There are four major types of prothrombin activators, which either convert thrombin to form the catalytically active meizothrombin (Group A and B) or to thrombin (Group C and D). From Maduwage K, Isbister GK. Current Treatment for Venom-Induced Consumption Coagulopathy Resulting from Snakebite. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014. 8(10): 1-13.

The standard treatment for snake envenomation is antivenom. (This is a technical term for something that is anti the venom.) In the 1950s antivenom was already part of the standard treatment of viper bites in Israel, though apparently it was then called by the far fancier name of "serum antivenimeux." (If chemistry or immunology is your thing, you can read more about how viper antivenom was made in Israel here.) These antivenoms work in a number of ways, one of which is by blocking the toxin and preventing it from binding to its target (i.e. those green diamonds in the diagram above).

snakes that heal

Snakes aren't only associated with coma, convulsions and death. They are - paradoxically - often associated with those who heal. Here is the cover of Fred Rosner's book; notice what looks like two snakes wrapped around a winged pole. Compare that image with the insignia of the US Army Medical Corps below.

The lower image is the caduceus, the rod carried by the Greek god Hermes (known as Mercury when in Rome). But in fact this double-snake flying-rod has nothing to do with healing, and is erroneously -though very widely- used as a medical emblem. But as an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association points out, the adoption of the double-snaked caduceus of Hermes - at least in the US - is likely due to its having been used as a watermark by the prolific medical publisher John Churchill.

The correct mythological association is with the Staff of Asklepios, the ancient Greco-Roman god of medicine. In one legend, a snake placed some herbs into the mouth of another serpent that Asklepios had killed, and the dead snake was restored to life. As a mark of respect, Asklepios adopted as his emblem a snake coiled around his staff. While the US Army Medical Corps uses the caducues as its badge, on its regimental flag the US Army Medical Command uses the more appropriate single snaked staff. Oh, and a rooster.

U.S. Army Medical Command Regimental Flag. Don't ask about the rooster...

Fortunately, the Israel Defense Forces clearly know a caduceus from an Asklepios. They adopted the correct Greco-Roman mythological symbol for the medical unit of the first Jewish army in 2,000 years.

The Greeks may have had their tradition, but we have ours. And in ours, it is never the snake that heals.

“עשה לך שרף ושים אותו על נס, והיה כל הנשוך וראה אותו וחי. וכי נחש ממית או נחש מחיה? אלא בזמן שישראל מסתכלין כלפי מעלה ומשעבדין את לבם לאביהן שבשמים היו מתרפאים, ואם לאו היו נימוקים...

”Make a fiery snake and place it on a pole, and it will be that anyone who is bitten will look at it and live” [Numbers 21:8] But is a snake the source of life and death? Rather, the verse means that when Israel looked up and submitted their heart to their Father in Heaven, they were healed, but if they did not do so, they perished.”