The Mishnah outlines some of the differences between the very first Passover that was celebrated while the Jews were still in Egypt, and the Passovers that were celebrated in the Temple in Jerusalem in the centuries that followed.

מַתְנִי׳ מָה בֵּין פֶּסַח מִצְרַיִם לְפֶסַח דּוֹרוֹת? פֶּסַח מִצְרַיִם מִקָּחוֹ מִבֶּעָשׂוֹר, וְטָעוּן הַזָּאָה בַּאֲגוּדַּת אֵזוֹב, וְעַל הַמַּשְׁקוֹף וְעַל שְׁתֵּי הַמְּזוּזוֹת, וְנֶאֱכָל בְּחִפָּזוֹן, בַּלַּיְלָה אֶחָד. וּפֶסַח דּוֹרוֹת נוֹהֵג כׇּל שִׁבְעָה

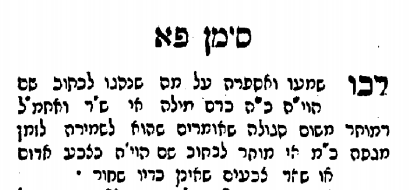

Image from here.

MISHNA: What are the differences between the Paschal lamb that the Jewish people offered in Egypt and the Paschal lamb offered in all later generations? The Paschal lamb the Jewish people offered in Egypt had to be taken from the tenth of the month of Nisan and required the people to sprinkle its blood with a bundle of hyssop, unlike the Paschal lamb in all later years, and its blood was also sprinkled upon the lintel and the two doorposts, and it was eaten with haste; in addition, the Paschal lamb in Egypt was only on one night, whereas the Paschal lamb throughout the generations is observed for seven days.

The Talmud spends several pages discussing the differences between that first Passover and all those that came later. As a rule, we don’t do much sprinkling of blood on our doorposts these days, but that was not always the case. Since we are still in the throes of a pandemic, let’s take a look at an overlooked custom that arose in Turkey during a pandemic there, and how it was connected to this Mishnah.

The BLoody Question

Rabbi Chaim Palagi (1788-1868) was an important rabbi and leader of the Jewish community in Izmir (Smyrna), Turkey, and his influence was felt far beyond. Among his many books (somewhere between seventy and eighty!) is a collection of responsa called Chaim Beyad (חיים ביד), in which he was asked the following question:

Come and listen and I will tell you about whether the custom to write God’s name [שם הוי׳ה ב׳ה] with the blood from a circumcision is appropriate. And if it is argued that it is indeed permitted, because it provides protection during an epidemic (heaven forbid), whether it is permitted to write God’s name in red or in any color other than in black ink…

So apparently the Jews of Izmir used to take the blood from a Jewish baby that had just been circumcised paint God’s ineffable name with it onto a flag or poster and presumably hang it somewhere for protection against a pandemic. (I know what you are thinking: why on earth was there so much blood? What exactly were they doing wrong? Fair questions, but let’s stay focussed.) This practice had its roots in that very first Passover, where the blood of a lamb painted on a doorpost signaled that there would be no death in the house, for it was under God’s protection.

Rabbi Palagi’s answer is technical and difficult to follow, but in the end he seems to allow the practice if the scribe is “a person of great learning and an expert in Kabbalah and there is a great need.” Moderns would, I am sure, find the whole practice quite distasteful, but it reminds us that when things are desperate and there aren’t a lot of options, prayer and folk magic are invoked in the face of a pandemic. Today there is no need to adopt this practice. We have a vaccine.