Small Gourds vs Big Gourds, or Cucumbers vs Gourds?

In the middle of a long discussion of the regulations allowing one sacrificial animal to be substituted by another we find this gem:

בוצינא טב מקרא

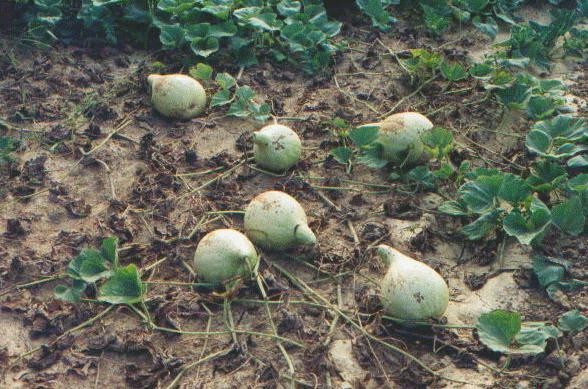

A small gourd now is better than a large gourd later (Temurah 9a).

Elsewhere Rashi (Ketuvot 83b) explains the meaning of this phrase:

בוצינא דלעת קטנה קרא דלעת גדולה והאומר לחבירו קח לך דלעת קטנה בגינתי או המתן עד שיגדילו וקח גדולה טוב לו ליקח הקטנה מיד כי לא ידע מה יולד יום

...When a person says to his friend "you may take this small gourd in my garden now or you can wait until it grows larger and then take it" it is better to take the small gourd immediately, because you cannot know what the future may bring.

This is a fairly unremarkable observation, and it finds a similar expression in the adage "a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush." The meaning is clear: it's better to have a small but certain gain rather than risk a larger one that is less certain (though see here for an interesting alternative origin of the expression). This is Rashi's explanation. But there is another way to explain the phrase (and this is followed by the Koren-Steinsaltz Talmud). According to Tosafot (Ketuvot 83b) cited in the name of Rabbenu Tam (d.1171), the proverb means the following:

ומשל הדיוט כך הוא שאדם אוהב הקישות יותר שיהנה בה מהרה ממה שהוא אוהב דלעת ולהמתינה אע"פ שהיא טובה יותר

This common saying means that a person would prefer [fast growing] cucumbers because he can enjoy them sooner, rather than gourds [which grow slowly and] which require waiting, even though they [taste] better. (Tosafot, בוצינא טב מקרא, Ketuvot 83b).

So according to the great Rabbenu Tam, this saying does not address any element of risk. Instead it is addressing the ability to have self-control and to plan for the future. The larger reward is certain, but is only available if you can wait. In fact, Rabbenu Tam is describing the famous Marshmallow Test.

The Marshmallow Test

The man behind the Marshmallow Test is the psychologist Walter Mischel, who was born in Vienna and fled to the US in 1938. Last September he died at the age of 88. Mischel was the emeritus chair of the Department of Psychology at Columbia University, and as his obituary in The New York Times noted, “his studies of delayed gratification in young children clarified the importance of self-control in human development, and…led to a broad reconsideration of how personality is understood.”

The Marshmallow Test is simple: give kindergarten children an option -one reward now (in the original experiments the children could choose any reward, not just a marshmallow) or two if you can sit and not touch the reward for fifteen minutes. The studies were performed at Stanford between 1968 and 1974 and involved some 550 children. If you haven't already seen what the test looks like, grab a coffee and watch the video. It's quite wonderful.

There have been dozens and dozens of academic papers written on the Marshmallow test, since Mischel first published his findings in 1969. But perhaps most surprisingly, the findings of the Marshmallow experiment on pre-schoolers seems to predict the future behaviors of the test subjects when they are adults. Here is Mischel summarizing his findings in his recent book called (predictably enough,) The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-Control.

“What the preschoolers did as they tried to keep waiting, and how they did or didn’t manage to delay gratification, unexpectedly turned out to predict much about their future lives. The more seconds they waited at age four or five, the higher their SAT sores and the better their rated social and cognitive functioning in adolescence. At age 27-32, those who had waited longer during the Marshmallow Test in preschool had a lower body mass index and better sense of self-worth, pursued their goals more effectively, and coped more adaptively with frustration and stress. At midlife, those who could consistently wait (“high delay”), versus those who couldn’t consistently wait (“low delay”), were characterized by distinctively different brain scans in areas linked to addictions and obesity.”

Wow. That's some test. But before you run out and test your preschool aged children (or grandchildren), remember that according to Tosafot, most people prefer a smaller instant reward to a larger but delayed reward. The classic Marshmallow Test measured how long young children could control their desires for an instant reward, but gives a new insight into this daf. If you can hold out for slow growing gourds rather than go for the faster growing cucumbers, you might just do very well in later life.