ואמר רבא זה בנה אב כל מקום שנאמר שה אינו אלא להוציא את הכלאים ...אמר לך ר"א כי איתמר דרבא לטמא שנולד מן הטהור ועיבורו מן הטמא...וטהורה מטמאה מי מיעברא אין דקיי"ל דאיעבר מקלוט

Rava said this establishes a model and teaches that wherever the term שה [seh] is stated in the Bible, it is meant to exclude a hybrid... R. Eliezer would say to you - when did Rava state his model? With respect to a non-kosher animal that was born from a kosher mother and a non-kosher father...But can a kosher animal conceive from a non-kosher animal? Yes, for it has been established that this case refers to a kosher animal that was conceived from a [kosher mutant animal that was] born with uncloven hooves. (Bava Kamma 77b-78a)

A pig in sheep's clothing? Nope. Just a pig.

In toady's page of Talmud we read of a debate regarding the crossbreeding of different species, and the possibility that a non-kosher animal (say, a pig) could fertilize a kosher animal (like a sheep). Here the Talmud seems to suggest that this could not happen, and that when this possibility is raised, it refers to a kosher animal that is breeding with another kosher animal but which looks non-kosher because of a mutation that causes it to have non-cloven hooves. Here is that case:

k= kosher; m= mutant, born with non-cloven hooves

This debate is part of a larger one found in another tractate of the Talmud, Bechorot. Here is part of that discussion:

והאמר ר' יהושע בן לוי לעולם אין מתעברת לא טמאה מן הטהור ולא טהורה מן הטמא ולא גסה מן הדקה ולא דקה מן הגסה ולא בהמה מן חיה ולא חיה מן בהמה חוץ מר' אליעזר ומחלוקתו שהיו אומרים חיה מתעברת מבהמה וא"ר ירמיה דאיעבר מקלוט בן פרה ואליבא דרבי שמעון

...R. Yehoshua ben Levi said: A non-kosher female can never conceive from a kosher male, nor a kosher female from a non-kosher male, nor a large animal from a small animal, nor a small animal from a large animal, nor a domesticated animal from a non-domesticated animal, nor a non-domesticated animal from a domesticated animal, except for R. Eliezer and his disputant [in Chulin 79b], who claimed that a non-domesticated animal can conceive from a domesticated animal...(Bechorot 7a)

Which leads to the question of the day: Can a kosher animal indeed successfully breed with a non-kosher animal? Let's take a look.

When a pig loves a sheep

Pigs have been known to act, well, like pigs, and copulate with sheep. (There's even a video of it, if you are interested). But could this lead to a baby peep, or ship, or whatever you'd like to call it? There are pictures that suggest this may be so, but in actual fact this pig with wool is the rare Hungarian Mangalitza pig, and has no sheep ancestry.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Foster Dwight Coburn, a farmer who also served as the secretary of the Kansas Department of Agriculture published Swine in America; a text-book for Breeder, Feeder and Student, and on page 63 he made the following observation:

There exists in some sections of Old Mexico a type of “hog” represented as the product of crossing a ram with a sow, and the term “Cuino” has been applied to this rather violent combination. The ram used as a sire to produce the Cuino is kept with the hogs from the time he is weaned. A resident of Mexico has given the following description of the Cuino: “The sow used to produce the Cuino belongs to any race, but as a rule to the Razor-Back family, which is the more numerous. There is never any difficulty with her accepting the ram when breeding time comes. The progeny is a pig—unmistakably a pig—with the form and all the characteristics of the pig, but he is entirely different from his dam if she is a Razor-Back. He is round-ribbed and blocky, his short legs cannot take him far from his sty, and his snout is too short to root with. His head is not unlike that of the Berkshire. His body is covered with long, thick, curly hair, not soft enough to be called wool, but which nevertheless he takes from his sire. His color is black, white-black, and white-brown and white. He is a good grazer and is mostly fed on grass with one or two ears of corn a day, and on these he fattens quickly. The Cuino reproduces itself, and is often crossed a second and third time with a ram. Be it what it may, the Cuino is the most popular breed of hogs in the state of Oaxaca, and became so on account of their propensity to fatten on little food.”

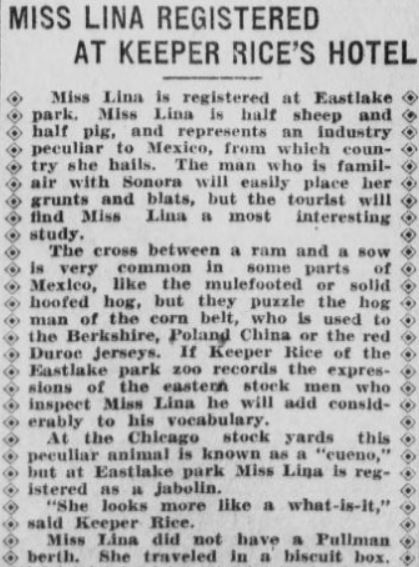

It may have been the most popular pig breed in Oxaca, but it was still rather an oddity in the US; newspapers found them interesting, as evidenced by two reports, from 1902 and 1908 about sheep-pig hybrids.

The Minneapolis Journal, September 24, 1902, from here.

Los Angeles Herald. October 3, 1908, from here.

Species and interbreeding

Despite these reports, it would seem that the rule suggested by R. Yehoshua ben Levi is correct. Different species cannot successfully interbreed, because, well, because that's the definition of a species, as the Oxford English Dictionary makes clear:

A group of living organisms consisting of similar individuals capable of exchanging genes or interbreeding. The species is the principal natural taxonomic unit, ranking below a genus and denoted by a Latin binomial, e.g., Homo sapiens.

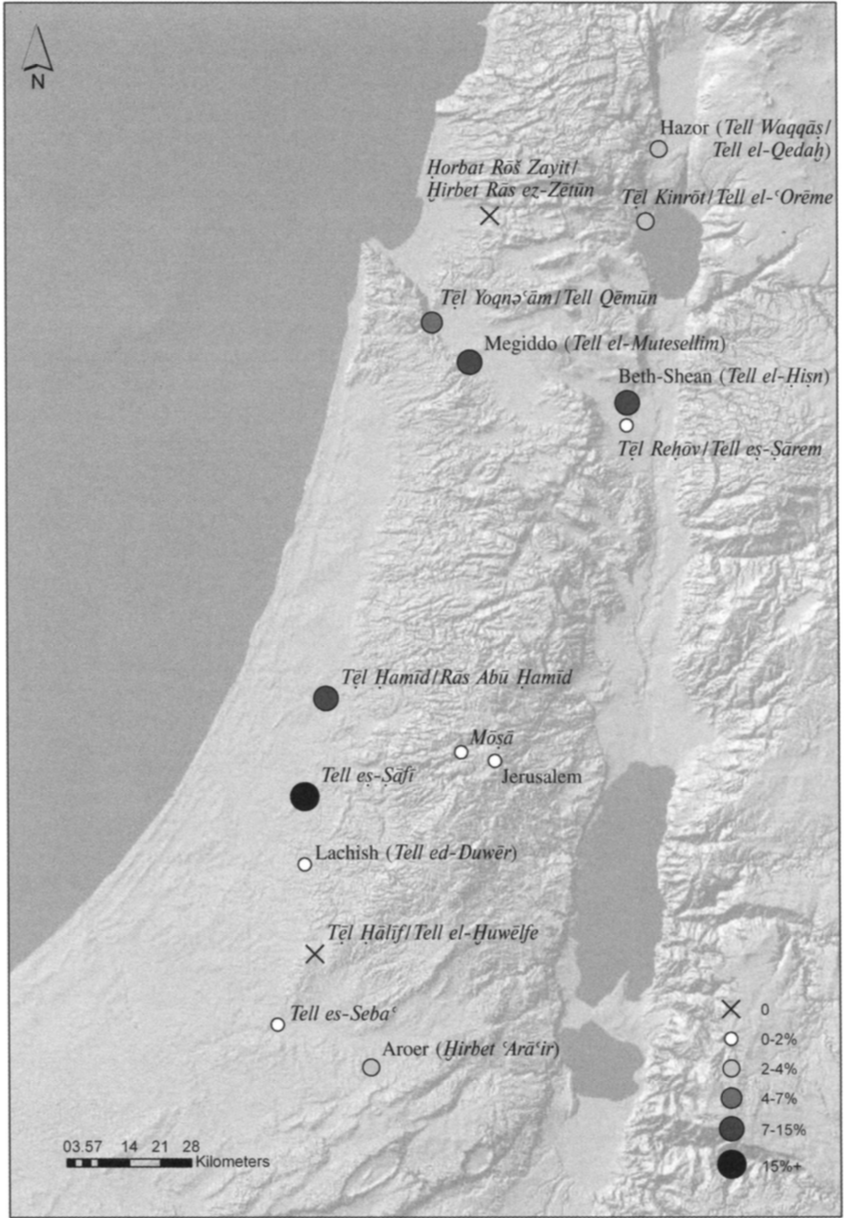

So although it is a tautology, you get the idea: a species by definition can only breed with other members of its own species. If a pig and a sheep could breed and have offspring, they'd be members of the same species. But they are not. Pigs belong to genus Sus, and the species Scrofa, whereas sheep belong to the genus Ovis and the species Aries. Pigs have 38 chromosomes, and sheep have 54. So they cannot cross-breed. (Lions and tigers both have 38 chromosomes, so they can cross breed, and produce a liger.)

But it's not as simple as that. Even if you don't have the same number of chromosomes, you can still sometimes breed outside your species. Horses have 64 chromosomes and donkeys have 62. Yet they can cross breed, resulting in a mule (if mom was a horse) or a hinny (if mum was a donkey), although these are nearly always sterile. Horses belong to the genus Equus and the species ferus, and donkeys belong to the same genus but to a different species, africanus. Yet they can interbreed. Which raises the question: should a horse and a donkey be re-classified as belonging to the same species? But that would be odd, because they look so different and act in very different ways.

These kinds of questions are perplexing, and have challenged the world of biology since the time of Carl Linnaeus (d. 1778) who gave the world a way of categorizing and naming all living things called binomial nomenclature. Briefly it goes like this: the grey wolf belongs to the genus Canis and the species lupus. Dogs belong to the same genus, Canis, and are a subspecies of wolves, so their scientific name is Canis lupus familiaris (which I suppose makes it a trinomial nomenclature). We belong to the genus Homo and the species sapiens, whereas chimpanzees belong to a different genus and species, Pan troglodytes. Anyway just what gets a creature into one species class or another is a really challenging question, one that is still being played out in the scientific literature. There's even a 320 page book from the University of California Press in which the author "provides a new perspective on the relationship between philosophical and biological approaches" to the concept of a species. For now, though, R. Yehoshua ben Levi's generalization found in Bechorot is pretty close to the Linnaean taxonomy we use today. We can also conclude that the general rule of the Talmud from today's daf, that a kosher animal could not successfully breed with a non-kosher one, is a pretty good rule of thumb.

“Every living thing loves its like,

and every person his own sort.

All creatures flock together with their kind.”