In honor of the birthday of my dear wife, Erica, who has taught me how to see the heavens and focus on the earth.

While discussing the legal technicalities involved in buying a boat, the Talmud digresses with a series of fantastic stories about boats, told by Rabbah bar bar Chanah. And then it digresses again with a series of fantastic stories about all kinds of things, also told by Rabbah bar bar Channah. In total he told fifteen stories. Here is the last one:

אמר לי תא אחוי לך היכא דנשקי ארעא ורקיעא אהדדי שקלתא לסילתאי אתנחתא בכוותא דרקיעא אדמצלינא בעיתיה ולא אשכחיתה אמינא ליה איכא גנבי הכא אמר לי האי גלגלא דרקיעא הוא דהדר נטר עד למחר הכא ומשכחת לה

An Arab also said to me: Come, I will show you the place where the earth and the heavens touch each other. I took my basket and placed it in a window of the heavens. After I finished praying, I searched for it but did not find it. I said to him: Are there thieves here? He said to me: This is the heavenly sphere that is turning around; wait here until tomorrow and you will find it again.

What should we make of this? We should begin by considering its context, noting that it is part of a series of fantastic fables. These include a man who pursued a demon on horseback, antelope the size of mountains, giant frogs ("the size of sixty houses") that are eaten by even more giant birds, a fish so large it took three days to sail between its fins, and scorpions the size of donkeys. You get the idea. Given this context, perhaps the tale of a place where heaven and earth touch as a description of reality should be taken with as much seriousness as the other stories. Which is to say, not very seriously at all.

Other Talmudic descriptions of the Cosmos

Not so fast. There are other rabbis in Talmud who address the structure of the earth and the cosmos. Rabbi Natan noted that the stars do not seem to change in their positions overhead when walking far distances. The assumption underlying his explanation for this observation was that the earth is flat. Covering the earth was an opaque cap referred to as the rakia, which is most commonly translated as the sky or firmament. Rava, a fourth-century Babylonian sage who lived on the banks of the river Tigris, determined this cap to be 1,000 parsa in width, while Rabbi Yehudah thought that he had over-estimated this thickness. There were others who added to the picture of the sky; Resh Lakish announced that it actually was made up of seven distinct layers. Given this model, there would have to be a place where the opaque cap touched the earth, a place that Rabbah bar Bar Channah claimed to have touched. So even allowing for a degree of talmudic fantasy, this fable was clearly built on the model that was shared by other rabbis in the Talmud.

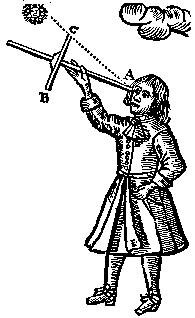

The Flammarion Engraving

In 1872, Camille Flammarion published L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire (The Atmosphere: Popular Meteorology). In the 1888 edition this engraving appeared on page 163:

As you can see from the caption, the engraving is "A missionary of the Middle Ages tells that he had found the point where the sky and the Earth touch." The engraving appears to have been specially created for Flammarion's book. The text that precedes it reads as follows:

Whether the sky be clear or cloudy, it always seems to us to have the shape of an elliptic arch; far from having the form of a circular arch, it always seems flattened and depressed above our heads, and gradually to become farther removed toward the horizon. Our ancestors imagined that this blue vault was really what the eye would lead them to believe it to be; but, as Voltaire remarks, this is about as reasonable as if a silk-worm took his web for the limits of the universe. The Greek astronomers represented it as formed of a solid crystal substance; and so recently as Copernicus, a large number of astronomers thought it was as solid as plate-glass. The Latin poets placed the divinities of Olympus and the stately mythological court upon this vault, above the planets and the fixed stars. Previous to the knowledge that the earth was moving in space, and that space is everywhere, theologians had installed the Trinity in the empyrean, the glorified body of Jesus, that of the Virgin Mary, the angelic hierarchy, the saints, and all the heavenly host.... A naïve missionary of the Middle Ages even tells us that, in one of his voyages in search of the terrestrial paradise, he reached the horizon where the earth and the heavens met, and that he discovered a certain point where they were not joined together, and where, by stooping his shoulders, he passed under the roof of the heavens.

Flammarion does not reference his source for the missionary of the Middle Ages who, like Rabbah bar bar Channah, claimed to have found the place were the heavens and earth meet. Despite this, his engraving has become very popular. A version of it appears on the cover of Daniel J. Boorstin's best selling work The Discoverers, and inside William Vollmann's Uncentering the Universe. And those are just the ones I know about from my own library. You can buy a color poster of it (where it is incorrectly described as a "medieval artwork") but if you are really dedicated you could always travel to San Fransisco where a tattoo parlor will create the image on your arm.

We know that Rabbah bar bar Channah's model of the universe is not correct, but his suggestion of a place where heaven and earth touch is both endearing and enchanting. (It is also the perfect name for an anthology of Midrash which was published back in 1983). With Rosh Hashanah approaching, you may already be thinking about your wine list. Perhaps you should consider a kosher wine whose label shows part of the Flammarion etching, and drink to the memory of Rabbah bar bar Channah.

![L'atmosphère_-_météorologie_populaire_-_[...]Flammarion_Camille_bpt6k408619m.jpeg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54694fa6e4b0eaec4530f99d/1490796746066-SZ91FZ3ZAN8PSKGAXUKI/L%27atmosph%C3%A8re_-_m%C3%A9t%C3%A9orologie_populaire_-_%5B...%5DFlammarion_Camille_bpt6k408619m.jpeg)