Last time on Talmudology

Although permitted by Jewish law, in Victorian Britain it was illegal for a man to marry his dead wife’s sister – though many did. There were attempts to change the law and permit this kind of marriage, but many in the Church of England remained opposed. Writing in 1887 in The British Medical Journal, an anonymous surgeon claimed that science could provide support for the permissive movement. But we now know that the science he offered (that all future children of a woman, regardless of the father, carry the traits of the man who first impregnated her) is wrong. This shows that science changes. But if science changes, what should we do when it seems to challenge Jewish tradition?

What is stuff made of?

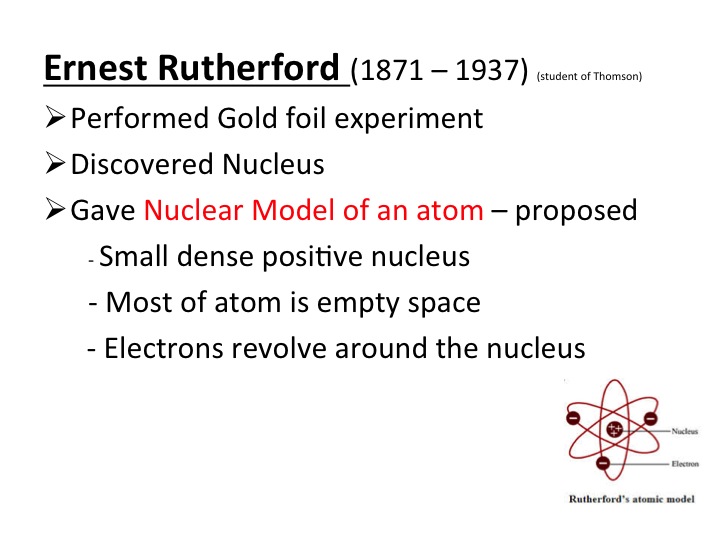

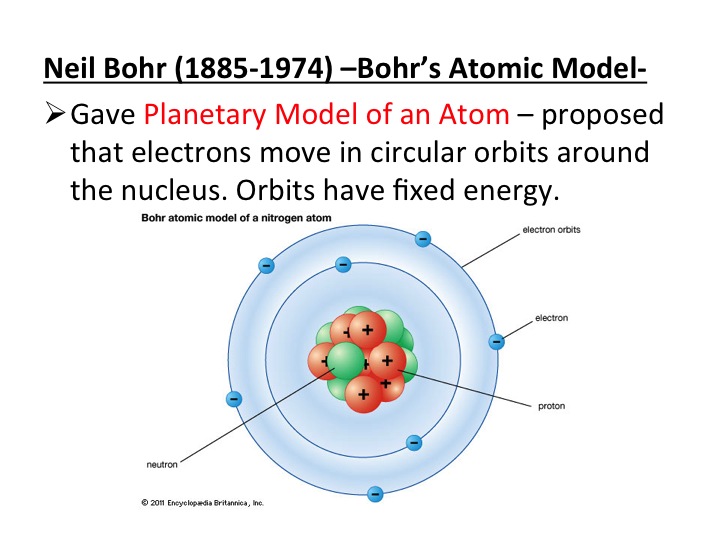

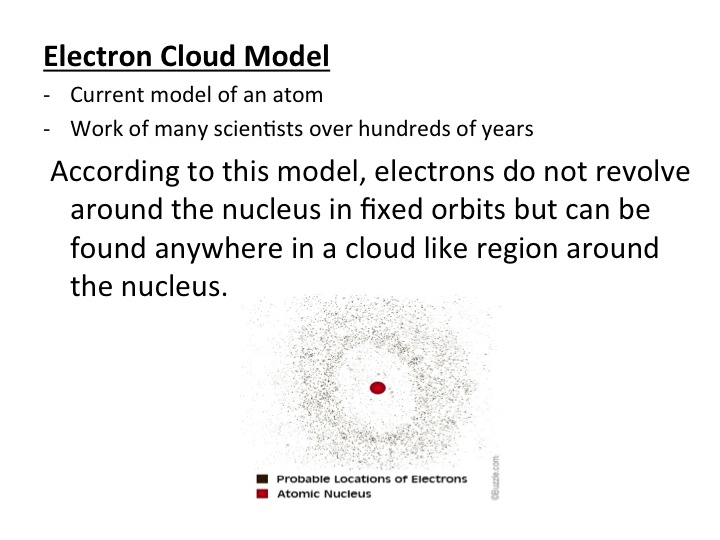

Several years ago, I had the pleasure of studying science with my then 13-year-old daughter Ayelet. She was preparing for a test, and the subject was “Atomic Structure.” Here is some of the content she shared with me: (Read it through - it's really not scary.)

(All slides courtesy of Berman Hebrew Academy, 8th Grade Science Class)

So to sum it up, Ayelet taught me that in addition to the model of Aristotle, we've had at least five explanations of what stuff is made of:

why don't kids reject science?

Now here is a fascinating thing. My daughter had no existential breakdown when she realized that the way scientists understand the world changes over time. She did not once say to me “Scientists are useless. They change their minds all the time. They must have no idea what they are talking about. I’m done with learning science…” Not even close (though, by the end, she was most certainly done with studying for her science test). Let's compare this attitude towards the changing nature of scientific knowledge with that of some Jewish thinkers, past and present.

reuven landau & foucault's pendulum

Let’s start with someone who is not well known (unless you read the book). Reuven Landau (d. 1883?) wrote strongly against the Copernican model of the solar system in which the sun is stationary and the earth revolves around it. But in 1851 Foucault demonstrated with his pendulum that the earth really was revolving, (though it didn’t prove that it revolved around the sun). What to do with this evidence? Landau had no doubt. Science was fickle and changed all the time, so don’t worry about it.

Although the astronomers of our time pride themselves on finding a compelling demonstration that the earth moves by using the pendulum, you should dismiss this too. For it has happened many times that an earlier scientist proved a point beyond a doubt using an unequivocal demonstration, and yet a later one came and disproved that which was established earlier, including the [previously] convincing demonstrations, and showed a new explanation for the findings...

This skepticism about accepting the results of the famous pendulum experiment reflected Landau's attitude towards science in general, which can be best summed up like this. Since all scientific theories are in a state of constant flux, it's best not to pay too much attention to them. When Jewish beliefs are challenged by science, take the long view; in doing so, tradition will ultimately be vindicated. (His view was actually more nuanced than that, insofar as he was willing to quote from the science when it supported his anti-Copernican position, but criticized the same science as being fickle when it proved to be problematic.)

Rav Kook

Abraham Isaac Kook (1865–1935), the first chief rabbi of Palestine, is thought to have welcomed science as a tool to understudying God's universe. While this is generally correct, (he was famously sympathetic to Darwin's theory, though in none of his writings does he mention Darwin by name,) Rav Kook cautioned against accepting all scientific theories "...even those about which there is general agreement, for they are like a fading flower (כי הן כציץ נובל). Soon enough new instruments will be developed, and people will mock these new theories . . . only the word of our God will last forever." Because scientific theories come and go so quickly, Rav Kook felt it was best not to get too attached to them.

The Ben Ish Hai

Joseph Hayyim (1834–1909) was born in Baghdad, where at the age of twenty-five, he succeeded his father as leader of the Jewish community. He authored a work that is widely read by Sephardic Jews to this day called Ben Ish Hai, but it was in another work that he advanced an example of extreme rabbinic skepticism towards science.

Even when [a scientific idea seems] persuasive, it is likely to be rejected and overturned, because later enlightened people will come to understand something that arises from the natural world that had not been understood by those earlier. [These earlier people] had invented their own system based on their understanding. When an objection to an earlier system arises, the entire system is destroyed, because when a foundation is destroyed the whole house crumbles...Over the last two thousand years a number of systems have been developed and overridden in the fields of natural sciences and astronomy. One builds and another destroys, like the building of [the Egyptian cities of] Pitom and Ramses.

Note the language the Ben Ish Hai uses here.

“When an objection to an earlier system arises, the entire system is destroyed, because when a foundation is destroyed the whole house crumbles.”

But is this a fair description of the scientific method? Did Bohr's atomic model (work for which he won the Nobel prize in 1922) really destroy the entire edifice of physics, or did it nudge it closer to the truth?

Pinhas hurwitz & Sefer Haberit

Sefer Haberit is probably the best selling Jewish book of science ever written. First published anonymously in 1797, it remains in print to this day. Its author, Pinhas Hurwitz from Vilna, wrote the book in two parts; the first was a scientific encyclopedia dealing with what he called human wisdom, and the second part dealt with divine wisdom, (and was ostensibly focussed on explaining a sixteenth century kabbalistic work by Hayyim Vital).

Hurwitz cautioned against ever accepting any particular scientific theory. His notion of the way science changes is certainly not as extreme as that of the Ben Ish Hai, but it placed him in a rather odd situation. Hurwitz didn't much like the new Copernican model of the universe with the earth revolving around the sun, but neither could he go back to the old geocentric model. So in the spirit of compromise he suggested following the model proposed by Tycho Brahe some two centuries earlier, the details of which need not detain us. But Hurwitz knew that this model had been utterly discredited in the scientific community. No problem, wrote Hurwitz, because science is always changing its mind. Perhaps one day this old discredited model will come back into favor, and when it does, it will pose less of a problem for traditional Jewish belief than the current widely accepted Copernican model.

. . . who knows if at a later time or in one of the many future generations that will come after ours, [Tycho's discredited] theory may be accepted. Then it may become permanently accepted, for this is the way among the Gentiles that some opinions have their moment. At times they are rejected and at other times they are accepted. Even if a theory is rejected from its very inception . . . eventually there may arise a person who adopts the theory and succeeds in spreading it across the entire world...

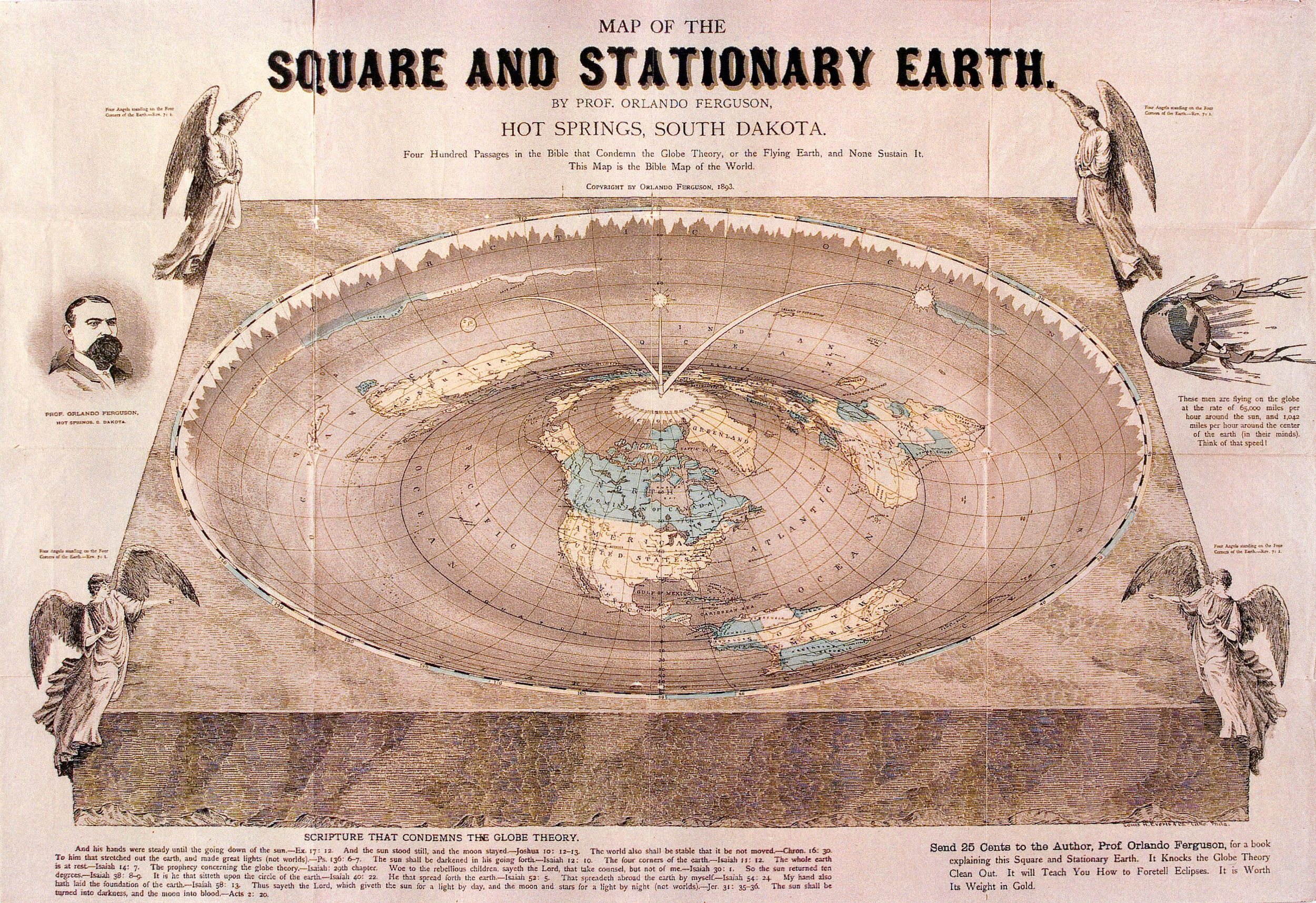

So according to Hurwitz, it made sense to accept a discredited theory that supported his notion of Jewish belief, because one day, perhaps, the scientists will go back to believing what they now reject as false. It is as if today, we claimed that it's perfectly reasonable to believe the world is flat, because that was once an accepted belief, and who knows, perhaps one day scientists will return to the flat-earth theory and believe once again that it is a true description of the world.

The Maharal of Prague

Another Jewish skeptic of science is the great Rabbi Judah Loew (d.1609), known by his acronym Maharal. In a long essay he contrasted knowledge attained from observation of the universe and knowledge obtained from Jewish tradition. The former is constantly changing, and inferior to the unchanging wisdom received through divine revelation.

... the [Gentile] nations want nothing more than to become wise through this knowledge, and indeed they became expert in this field of knowledge, as all know. Yet there always came other experts afterwards who overturned the knowledge that they had worked so hard to attain...However the Sages of Israel who received their information from Moses at Sinai—and who himself received this from God—are the only ones who alone possess the Truth...

Note that the Maharal made an expansive claim (and one that was very popular circa 1580): all true knowledge comes from religion - or more precisely - from the rabbis. He did not say that the rabbis provided spiritual insights while "experts" (who we'd call "scientists" today) provided insights into the physical universe. Rather he claimed that truth can only come from the "Sages of Israel who received their information from Moses at Sinai". As a consequence, scientists really have no seat at the table when we discuss knowledge.

rabbi moshe meiselman

The last example we will look at is a contemporary figure, Rabbi Moshe Meiselman. His recent book states that he "was trained by some of the great names in mathematics, philosophy and the sciences at two of America's premier universities." Great! Rabbi Meiselman has studied outside of the walls of the Jewish ghetto - something the Maharal could not do, even if he had wanted. So we should expect a fresh and sophisticated approach from a rabbi who gets science, right? Wrong.

Science has no sacred cows. Over the past hundred years, scientific theories have changed with unprecedented rapidity. Whoever weds his belief system to any particular scientific theory will soon find that system outdated and will be forced to look for a new one... (585)

Rabbi Meiselman here has the same old understanding of science as the Ben Ish Hai. When a new scientific theory replaces an older one, everything comes crashing down and we are left wandering in search of something new to grab on to. Elsewhere though, he sounds more like the Maharal, who objected to scientific hubris, and reminded us that science can make no truth claims, for these are reserved for the rabbis.

[A]t every juncture, just as soon as the dust of the latest revolution has settled, one inevitably finds scientists claiming that the ultimate secrets often universe have finally been unlocked and that there are few surprises left in store...Absolute truth has been attained! (584)

Now in fairness to Rabbi Meisleman, elsewhere in his long book he shows a better understanding of the scientific method.

Science, when properly understood, lays no claim to the knowledge of truth. It embodies the search for theories that approach the truth. It inches in the direction of truth, but it never claims to be in possession of that precious commodity. (579)

Which is it then, Rabbi Meiselman? Do scientists claim to have attained the Truth (as he writes), or rather are they engaged in a process that brings us ever closer to this goal without their having arrived (as he also writes)? His is a a peculiar mix of positions. (You can read other critiques of Rabbi Meiselman's book here and here.)

Got a spare five minutes? Great, then we can go a little deeper, and see why these rabbinic philosophies don't really reflect what science is all about. To do that, let's consider the truth claims of the following pairs of scientific statements.

1. The earth is flat vs The earth is round.

Both of these statements are incorrect. The earth is actually an oblate spheroid, that is, a globe which is slightly flattened at the poles. But the statement "the earth is round" is much closer to the truth than the claim that "the earth is flat."

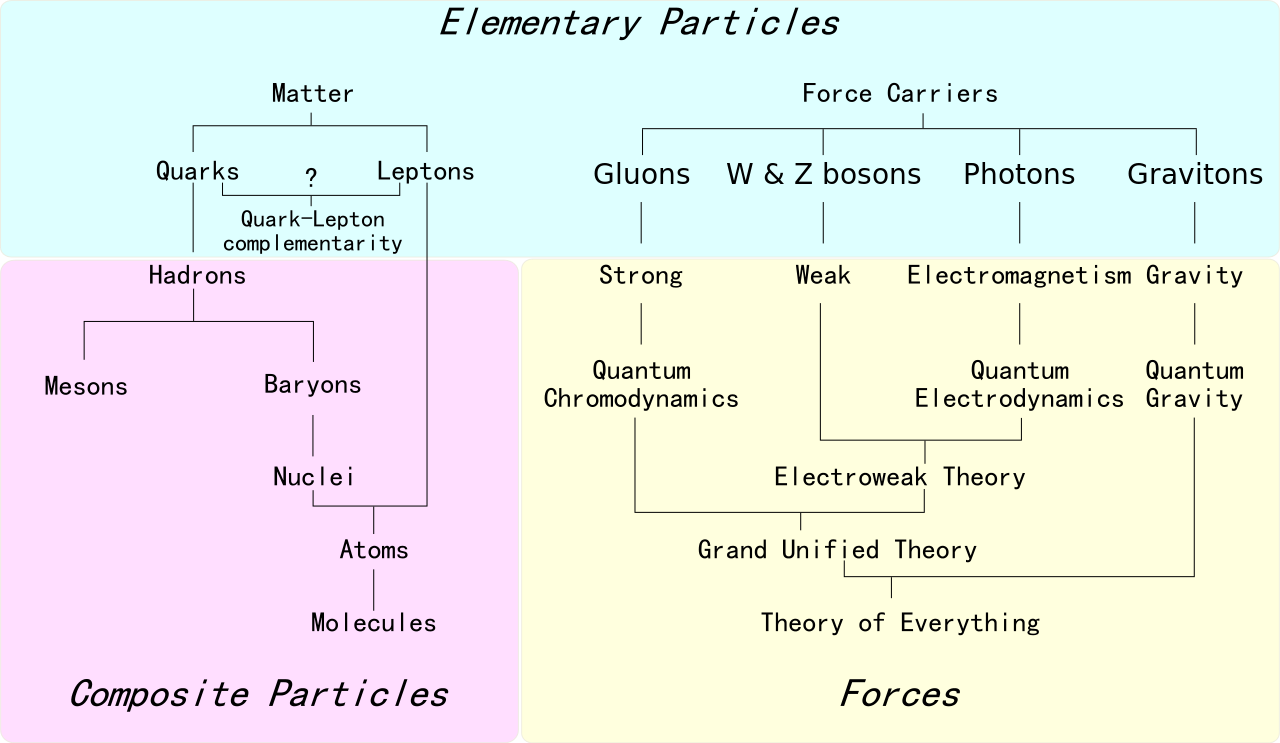

2. All matter consists of just four elements vs All matter is made up of just electrons and protons.

Again, both are false, but the second statement is a lot less false than the first. Matter is certainly not just made up of the four elements of earth, air, fire and water. But it's also not just made up of electrons and protons; matter is now known to be made up of neutrinos and muons, and up quarks and down quarks and charm quarks and who what knows other kinds of elementary particles still waiting to be discovered. The second statement is truer that the first, but physicists would not claim that it's the last word on the subject.

3. Vitamins prevent cancer vs vitamins don't prevent cancer

Here is starts to get complicated. While some studies are pretty conclusive (no-one really suggests that smoking doesn't cause lung cancer) other scientific claims seem to change over time. For example, the relationship between vitamins (especially vitamin D) and cancer is one that we have had different scientific answers to at different times. In 1999 the N-HANES study of over 5,000 women followed for twenty years reported that vitamin D was associated with a reduction in breast cancer. Then in 2007 the Journal of the National Cancer Institute looked at a group of 36,000 women in the Women's Health Initiative. It reported that there was no effect of vitamin D on the risk of breast cancer. Today, the official position of our National Cancer Institute is this: it still isn't sure if there is any association.

And now a forth scientific claim, this time from the field of mathematics

4. In a right angleD triangle, the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides.

This theorem (like all mathematical theorems) is true in a special way. So long as we're talking about two dimensional geometry, then this theorem will be true in all possible places in the universe; it was always true in the past, and it will always be true in the future. That's what makes a mathematical theorem true in a different way from a medical truth, or a truth about the physical universe. The latter two may be partially true, or true of the basis of the best equipment we have available, but these are not true in the way that the Pythagorean theorem is true.

KINDS OF SCIENCE

So there are different kinds of scientific claims, some of which are more true than others. And scientific progress advances in different ways depending on which area of knowledge we are addressing. These differences were not noted by any of the rabbinic critics we've cited above, but once understood, they allow us to appreciate that science can make different claims over time and that some of these can change without the entire scientific enterprise being called into question.

One last thing- be careful of any appeal to relativism. It could be argued that each of the rabbis we cited (well, other than Rabbi Meiselman) lived at a time when these subtleties were not appreciated. As a result we should not be a harsh judge of their philosophies of science, which just reflect the way people thought at that time. I am sympathetic to this claim, and I think it is a perfectly reasonable explanation of how they may have arrived at their opinions. But if these rabbis were just reflecting the way everyone thought when they lived, we are most certainly not bound to consider these opinions as anything other than of historical interest. And since we now know differently, we can ignore these rabbinic opinions as we forge our own Jewish philosophies towards science. If, on the other hand, the claim is made that these rabbis were reflecting a profound Jewish Truth that will remain so for ever, well, then we have a problem. Because you are then forced to reject the science, and end up arguing for all kinds of things we know are simply not true.

One other last thing. This is not a claim that science is the only path to knowledge, happiness and enlightenment. I am not suggesting anything like that. Steven Pinker argued for something along these lines in the pages of The New Republic (ז'לֹ), and Leon Wieseltier wrote a persuasive response, both of which are well worth reading. (I find myself more sympathetic to the latter than the former.) But when it comes to scientific questions, well, that is where science does, perhaps know best.

“Science confers no special authority, it confers no authority at all, for the attempt to answer a nonscientific question.”

where we've been

We noted that 130 years ago the laws of Yibbum were explained with a scientific fact that today we know is incorrect. This example raises the possibility that the scientific enterprise is only ever tentative and should be best ignored when it seems to raise questions about Jewish teachings. But that doesn’t really capture the way science progresses. We examined six rabbinic understandings of the philosophy of science, and noted that they do not capture the different meanings we have when we way that something is a fact of science.

We need some new Jewish philosophies of science. They must take into account these different meanings, and need to be more sophisticated than the rabbinic understandings that we examined. There have been some really good efforts to address this area (like here and here and here), but more work needs to be done. Who wants a shot?