Today we learn one of the central texts in the Talmud that discusses the relationship between experience and authority.

חולין נז, ב

…אמרו עליו על רבי שמעון בן חלפתא שעסקן בדברים היה

מאי עסקן בדברים? א"ר משרשיא דכתיב (משלי ו, ו) "לך אל נמלה עצל ראה דרכיה וחכם אשר אין לה קצין שוטר ומושל תכין בקיץ לחמה" אמר איזיל איחזי אי ודאי הוא דלית להו מלכא

אזל בתקופת תמוז פרסיה לגלימיה אקינא דשומשמני נפק אתא חד מינייהו אתנח ביה סימנא על אמר להו נפל טולא נפקו ואתו דלייה לגלימיה נפל שמשא נפלו עליה וקטליה אמר שמע מינה לית להו מלכא דאי אית להו הרמנא דמלכא לא ליבעו

א"ל רב אחא בריה דרבא לרב אשי ודלמא מלכא הוה בהדייהו א"נ הרמנא דמלכא הוו נקיטי אי נמי בין מלכא למלכא הוה דכתיב (שופטים יז, ו) בימים ההם אין מלך בישראל איש הישר בעיניו יעשה אלא סמוך אהימנותא דשלמה

They said about Rabbi Shimon ben Chalafta that he was a researcher of various matters… The Gemara asks: From what episode did Rabbi Shimon ben Chalafta earn the title: Researcher of matters? Rav Mesharshiyya said: He saw that it is written: “Go to the ant, you sluggard; consider her ways, and be wise; which having no chief, overseer, or ruler, provides her bread in the summer” (Proverbs 6:6–8). Rabbi Shimon ben Chalafta said: I will go and see if it is correct that they have no king.

He went in the season of Tammuz, i.e., summer. Knowing that ants avoid intense heat, he spread his cloak over an ant hole to provide shade. One of the ants came out and saw the shade. Rabbi Shimon placed a distinguishing mark on the ant. It went into the hole and said to the other ants: Shade has fallen. They all came out to work. Rabbi Shimon lifted up his cloak, and the sun fell on them. They all fell upon the first ant and killed it. He said: One may learn from their actions that they have no king; as, if they had a king, would they not need the king’s edict to execute their fellow ant?

Rav Acha, the son of Rava, said to Rav Ashi: But perhaps the king was with them at the time and gave them permission. Or perhaps they already had permission from the king to kill the ant. Or perhaps it was a time between kings, as it is written: “In those days there was no king in Israel; every man did that which was right in his own eyes”(Judges 17:6). Rather, rely on the credibility of Solomon, the author of Proverbs, that ants have no king.

The “experimenter”?

There is a great deal to unpack in this passage. First we need to understand exactly what is meant by the term used to describe Rabbi Shimon: “עסקן בדברים.” It can be translated in a few ways, each with their own subtle meanings.

Literally translated, the words mean he was involved in things. The Steinsaltz (Koren) Talmud translates the phrase as researcher of various matters, while the Schottenstein (ArtScroll) Talmud translates it as an experimenter, echoing the earlier Soncino translation an experimenter in all things. Goldschmidt's German translation (the first translation of the entire Babylonian Talmud, published 1897-1935) states “das er sich mit Dingen zu befassen pflegte” that Rabbi Shimon “used to deal with things.”

But there is more to the Schottenstein translation, which adds the following note: “Literally: one who involved himself with matters; i.e. he performed experiments to test the veracity of propositions.” Now that is quite a claim, for it suggests that 1) Rabbi Shimon sought to validate, and by definition invalidate the truth claims of the Bible and 2) that there was a scientific method as far back as Rabbi Shimon, circa 200 C.E.

Who was Shimon ben Chalafta?

We know rather little of the life of Rabbi Shimon, although he is the subject of several aggadic legends. He was extremely poor but fortunately he was also the object of divine intervention. Rabbi Shimon was saved from a nasty end involving lions by the miraculous appearance of heavenly meat (Sanhedrin 59b), and was the recipient of another heavenly gift - a gem of great wealth - which enabled to him to buy food for Passover (which goes to show that the high cost of kosher food for Passover is a long Jewish tradition).

And what about that title “the experimenter”? What else did he check out, or examine, or decipher? Alas, we will never know. This is the only place in all of Jewish literature in which he is described as

עסקן בדברים.

The origins of the experiment

The first scientific experiment, claims the historian of science David Wootton, happened on September 19, 1648. It involved measuring the height of a tube of mercury (in what we would later call a “barometer”) at various elevations in the region of Massif Central in central France. (The height of the mercury was three inches lower at the top of a 3,000 foot summit than it was back home in the garden.) It was the “first proper experiment” writes Wootton,

in that it involves a carefully designed procedure, verification (the onlookers are there to ensure this is really a reliable account), repetition, and independent replication, followed rapidly by dissemination.

Of course there had been earlier experiments - Ptolemy and Galen had carried them out, and among the most famous early experiment was the one performed by the Arab scientist Ibn al-Haytham. In the eleventh century he demonstrated (at least to his own satisfaction) that the eyes work by receiving light, rather than by emitting it. But before the scientific revolution there had been remarkably few such experiments, and certainly none like the barometer experiment. Aristotle was likely to blame, for two reasons. First, he assumed that adequate knowledge of any subject he discussed was already available, and second, “the Aristotelian tradition insisted that the highest form of knowledge was deductive, or syllogist knowledge.”

In addition, there was the status of the Bible as a source of knowledge about the world. Since it was the word of a God who did not lie, its observations were no less important than any experimental or philosophical proofs. (Elsewhere we have examined in some detail rabbinic philosophies and the scientific method, and I am told there is a great book on the relationship between science and rabbinic thought.)

In a nutshell, the scientific method involves making a prediction and then carrying out an experiment to verify - or falsify it. The great philosopher of science Karl Popper (d. 1994) took it a stage further, and introduced the concept of falsifiability. For a statement to be scientific he claimed, it must be falsifiable, that is, it must make a declaration that can be tested. And Rabbi Shimon was doing no such thing.

What was Rabbi Shimon doing?

Rabbi Shimon was certainly not carrying out an experiment in any way we use the word today. Instead he was observing nature, and noting how things seemed to work. And this is no small matter. In this respect he was like Charles Darwin who also carried out meticulous observations. On the basis of these Darwin developed a theory, which in his case was the theory of evolution, a theory that, as it turned out, is indeed falsifiable.

Neither Rabbi Shimon ben Chalafta nor Rav Acha would have declared the words of Proverbs incorrect based on any of their own observations. What is more, some one-hundred and fifty years later, Rav Acha questioned Rabbi Shimon’s methodology. Why, he asked, is Rabbi Shimon so certain that his observations lead to his conclusion? Perhaps there were other explanations of what Rabbi Shimon had observed that would conclude, contra his deduction, that an ant colony actually had a king. Rav Acha makes a point that would be echoed in rabbinic texts centuries later: observations of the natural order can be explained in any number of ways; the only privileged source of knowledge is the Bible.

“Now of all the branches of Natural History, Entomology is unquestionably the best fitted for thus disciplining the mind of youth...no study affords a fairer opportunity of leading the young mind to the great truths of Religion, and of impresing it with the most lively ideas of the power, wisdom, and goodness of the Creator.”

And do ants have kings?

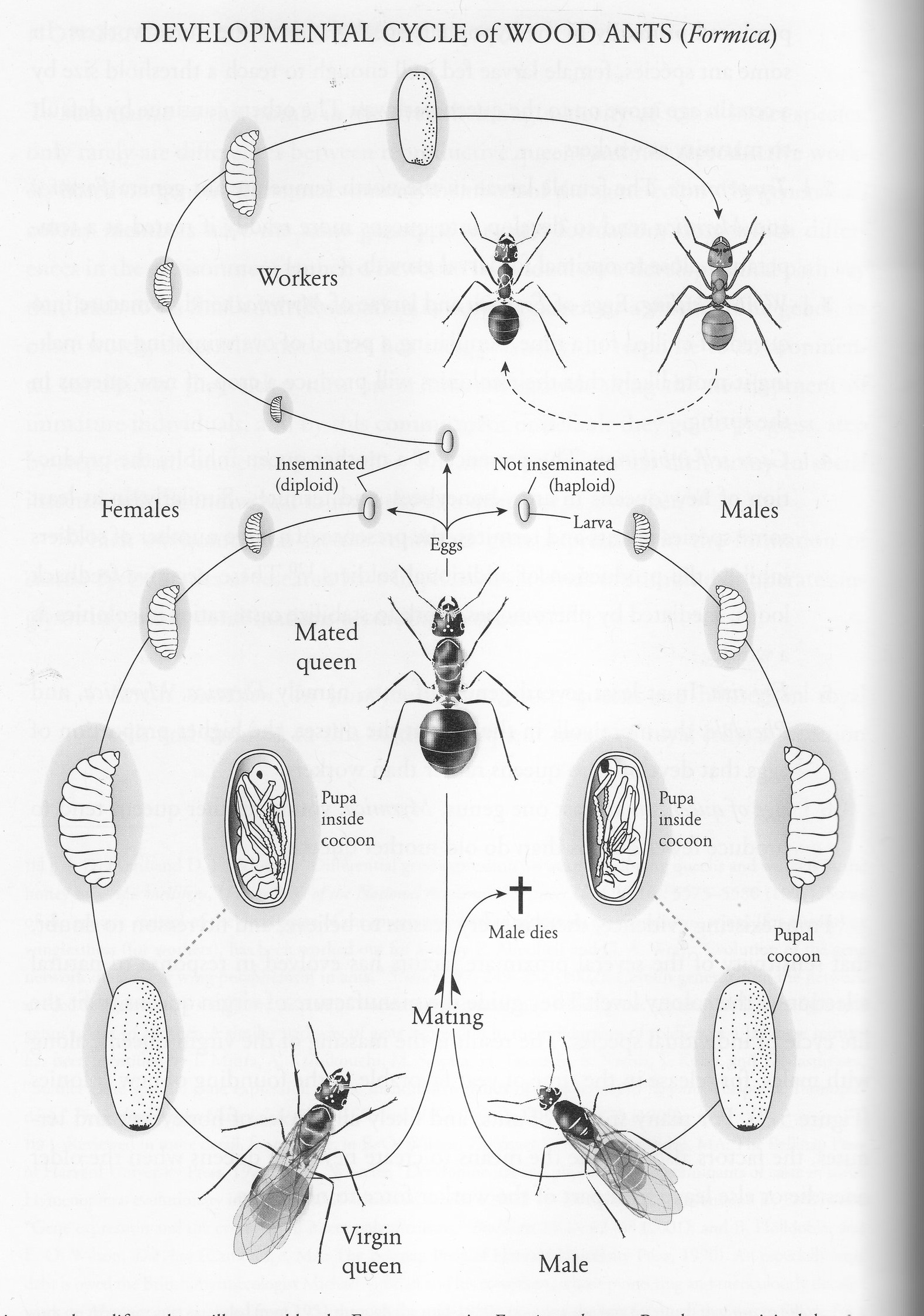

Basic ant colony life. From and Holldobler and Wilson. The Super-Organism; The Beauty. Elegance and Strangeness of Insect Colonies. Norton 2009. 138

No. They have Queens. Who are like kings except they are not male. Although this is generally true, it is not the case for all species of ants. E.O. Wilson and Bert Holldobler won a Pulitzer Prize for their now classic 1990 work, The Ants. Holldobler is a Professor of Life Sciences at Arizona State University, and Wilson is a Harvard Professor who has been studying ants for over five decades, so together they must really knows their stuff. “In the Australian Pachycondyla sublaevis” they wrote in their beautiful book The Superorganism “there is no anatomically distinct queen. Instead the top-ranked worker mates and lays eggs… and joins those just beneath her in caring for the brood, while the workers of lower rank forage outside the nest for food.”

To summarize: Ant colonies do not have kings, and usually (but not always), they have a queen. (Though to further complicate matters more the Formica Yessenis ant of Japan can have, in Wilson’s words “millions of queens.”) And so King Solomon was not correct when he wrote “"אין לה קצין שוטר ומושל” - that ants have “no chief, overseer, or ruler” (although I guess you could re-interpret the verse to mean that they have no ruler in the sense of how we use the word today).

But Rabbi Shimon was correct about there being various castes or ranks within the nest. He described how one ant was killed by others of the same cast, and in fact this may occur for a number of reasons. For example, in a 2013 paper titled Enforcement of Reproductive Synchrony via Policing in a Clonal Ant, the authors note that “worker policing controls genetic conflicts between individuals and increases colony efficiency.” In other words, the colony will control reproductive rights by turning on, and in some cases killing, other members of the nest. And in a letter to Nature, researchers reported that if the queen is challenged by another female she chemically marks the pretender who is then punished by low-ranking females.

Seeing the Divine in the Insect

Rabbi Shimon made his observations about the social structure of ants about 1,600 years before William Kirby who in 1808 published his “Introduction to Entomology” the very first general study of entomology. But like many works of science from the Victorian-era it is also a book about God. Throughout, Kirby notes the truth of Scripture and the stamp of a Divine Creator, which he insists can be recognized by studying insects. In this regard, Kirby was echoing exactly the sentiment in the Book of Proverbs cited in today’s page of Talmud. “Go to the ant, you sluggard; consider her ways, and be wise.”

Rabbi Shimon wasn’t the only tanna who saw the divine in the insect world. In a few pages (63a) we will read that when Rabbi Yochanan would study ant behavior, he would say a verse from Psalm 37:7 “צדקתך כהררי אל” Your righteousness is like the mighty mountains.” Why? Because, explains Rashi, God provides food for the ants, who then do not need to work hard to sustain the colony. It’s a beautiful homily, though once you read through The Ants, the suggestion that ants have it easy is fanciful.

“The author of Scripture is also the author of Nature: and this visible world, by types indeed, and by symbols, declares the same truths as the Bible does by words. To make the naturalist a religious man – to turn his attention to the glory of God, that he may declare his works, and in the study of his creatures may see the loving-kindness of the Lord – may this in some measure be the fruit of my work…’ ”

Rabbi Shimon ben Chalafta left no halachic teachings, and the only example we have of his inquisitive mind is today’s story about his field observations of ants. But he left an indelible mark on the oral tradition, because the Mishna, upon which all later Talmudic discussions are based, ends with his wise words.

“אָמַר רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן חֲלַפְתָּא, לֹא מָצָא הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא כְּלִי מַחֲזִיק בְּרָכָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל אֶלָּא הַשָּׁלוֹם, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר (תהלים כט), ה’ עֹז לְעַמּוֹ יִתֵּן ה’ יְבָרֵךְ אֶת עַמּוֹ בַשָּׁלוֹם

Rabbi Shimon ben Chalafta said: The Holy One, blessed be He, found no vessel that can [sufficiently] hold the blessing for Israel, save for peace, as the verse says, (Psalms 29:11) “God will give strength to His nation, God will bless His nation with peace.””

And let us say Amen.