This week’s Torah reading warns us not to be persuaded by a person who claims to be a prophet, which is to say, they claim to predict the future. There is, apparently a simple test: did the prediction come true? If it did, then that person is a real prophet.

דברים 18: 9-22

כִּי אַתָּה בָּא אֶל־הָאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר־יְהֹוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ נֹתֵן לָךְ לֹא־תִלְמַד לַעֲשׂוֹת כְּתוֹעֲבֹת הַגּוֹיִם הָהֵם… וַיֹּאמֶר יְהֹוָה אֵלָי הֵיטִיבוּ אֲשֶׁר דִּבֵּרוּ׃ נָבִיא אָקִים לָהֶם מִקֶּרֶב אֲחֵיהֶם כָּמוֹךָ וְנָתַתִּי דְבָרַי בְּפִיו וְדִבֶּר אֲלֵיהֶם אֵת כל־אֲשֶׁר אֲצַוֶּנּוּ׃ וְהָיָה הָאִישׁ אֲשֶׁר לֹא־יִשְׁמַע אֶל־דְּבָרַי אֲשֶׁר יְדַבֵּר בִּשְׁמִי אָנֹכִי אֶדְרֹשׁ מֵעִמּוֹ׃ אַךְ הַנָּבִיא אֲשֶׁר יָזִיד לְדַבֵּר דָּבָר בִּשְׁמִי אֵת אֲשֶׁר לֹא־צִוִּיתִיו לְדַבֵּר וַאֲשֶׁר יְדַבֵּר בְּשֵׁם אֱלֹהִים אֲחֵרִים וּמֵת הַנָּבִיא הַהוּא׃ וְכִי תֹאמַר בִּלְבָבֶךָ אֵיכָה נֵדַע אֶת־הַדָּבָר אֲשֶׁר לֹא־דִבְּרוֹ יְהֹוָה׃ אֲשֶׁר יְדַבֵּר הַנָּבִיא בְּשֵׁם יְהֹוָה וְלֹא־יִהְיֶה הַדָּבָר וְלֹא יָבֹא הוּא הַדָּבָר אֲשֶׁר לֹא־דִבְּרוֹ יְהֹוָה בְּזָדוֹן דִּבְּרוֹ הַנָּבִיא לֹא תָגוּר מִמֶּנּוּ׃

When you enter the land that the LORD your God is giving you, you shall not learn to imitate the abhorrent practices of those nations…I will raise up a prophet for them from among their own people, like yourself: I will put My words in his mouth and he will speak to them all that I command him; and if anybody fails to heed the words he speaks in My name, I Myself will call him to account. But any prophet who presumes to speak in My name an oracle that I did not command him to utter, or who speaks in the name of other gods—that prophet shall die.” And should you ask yourselves, “How can we know that the oracle was not spoken by the LORD?” if the prophet speaks in the name of the LORD and the oracle does not come true, that oracle was not spoken by the LORD; the prophet has uttered it presumptuously: do not stand in dread of him.

In The Madhouse — Plate 8. From A Rake's Progress, William Hogarth, 1734.

In my professional career as an emergency physician in Washington DC, I met many prophets. Most were on their way to the White House with an urgent message for the President. Most ended up being committed to an in-patient psychiatric hospital where they could get help for their psychosis. Today, we often - and correctly - associate a claim of prophecy as being associated with a mental health disorder. And so this week on Talmudology on the Parsha we will examine the relationship between prophecy and mental illness.

בבא בתרא יב, ב

א"ר יוחנן מיום שחרב בית המקדש ניטלה נבואה מן הנביאים וניתנה לשוטים ולתינוקות

Rabbi Yochanan said: "After the destruction of the Holy Temple the power of prophecy was taken from the prophets and given to the mentally ill and to children.

In the tractate Bava Basra in the Babylonian Talmud, Rabbi Yochanan declares not that prophecy is dead, but that the kind of things once said by the prophets of the Bible will henceforth be said by those with mental illness (שוטים) and children. Rabbi Yochanan may have been the first to see the overlap of mental illness and the kinds of things once said by prophets of the Bible, but today psychiatrists and others involved in the care of the mentally ill have noted this overlap too.

Abraham and Moses on the Psychiatrist's Couch

In 2012, three psychiatrists from the Harvard Medical School asked a simple question: How does a psychiatrist today help a patient to understand that their psychotic symptoms are not caused by supernatural visitations, "when our civilization recognizes similar phenomena in revered religious figures?" So the psychiatrists set off to examine the way in which revelation of the divine was described in the Bible, "with the intent of promoting scholarly dialogue about the rational limits of human experience." All this was to "educate persons living with mental illness, healthcare providers, and the general public that persons with psychotic symptoms may have had a considerable influence on the development of Western civilization."

They analyzed four religious figures, including two from our tradition, from a behavioral, neurologic, and neuropsychiatric perspective. They found that, based on the text of the Bible, Abraham had no affective, neurological or medical conditions, and since he showed no evidence of disorganization, they doubted that Abraham had classic schizophrenia too. But they raised the possibility of his having paranoid schizophrenia. This is a subtype of schizophrenia "that tends to manifest little or no disorganization, has preserved functional affect, and is associated with better occupational and social functioning." The psychiatrists based this diagnosis on the voices Abraham kept hearing, and "a very Abraham-centered worldview of dispensing universal blessings and curses based on one’s interactions with Abraham." Moses had "auditory and visual hallucinations of a grandiose nature with delusional thought content." He also exhibited "hyperreligiosity, grandiosity, delusions, paranoia, referential thinking, and phobia (about people viewing his face)." They were not certain though, if Moses displayed symptoms of paranoid schizophrenia, or if instead, he may have had a bipolar disorder. Jesus also displayed auditory and visual hallucinations, "delusions, referential thinking, paranoid-type thought content, and hyperreligiosity"(!) The Harvard psychiatrists also note that the lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia is 5-10%, and that Jesus "appears to have deliberately placed himself in circumstances wherein he anticipated his execution." Finally Paul is analyzed. He seems to have had a large number of auditory and visual perceptual experiences "that resemble grandiose hallucinations with delusional thought content." They reject the suggestion that he suffered from temporal lobe epilepsy, and they note that Paul wrote a great deal. This kind of productive writing, they claim, "tends to be more strongly associated with mood disorders than psychosis or epilepsy. This is persuasive toward Paul having a mood disorder, rather than schizophrenia or epilepsy."

Murray, E. Cunningham M. Price B . The Role of Psychotic Disorders in Religious History Considered. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 2012; 24:410–426

The point of all this analysis was not to test the the faith of those who believe in the prophetic abilities of Abraham, Moses, Jesus or Paul. Rather, it was to emphasize how those with what we today would describe as the florid symptoms of mental illness are revered as religious teachers. And one more thing. They claimed not to have any disrespect for those with religious beliefs towards any of these four figures.

Discussion about a potential role for the supernatural is outside the scope of our article and is reserved for the communities of faithful, religious scholars, and theologians, with one exception. It is our opinion that a neuropsychiatric accounting of behavior need not be viewed as excluding a role for the supernatural. Herein, neuropsychiatric mechanisms have been proposed through which behaviors and actions might be understood. For those who believe in omnipotent and omniscient supernatural forces, this should pose no obstacle, but might rather serve as a mechanistic explanation of how events may have happened. No disrespect is intended toward anyone’s beliefs or these venerable figures.

Nocturnal Hallucinations in Israeli Ultra-Orthodox Jews

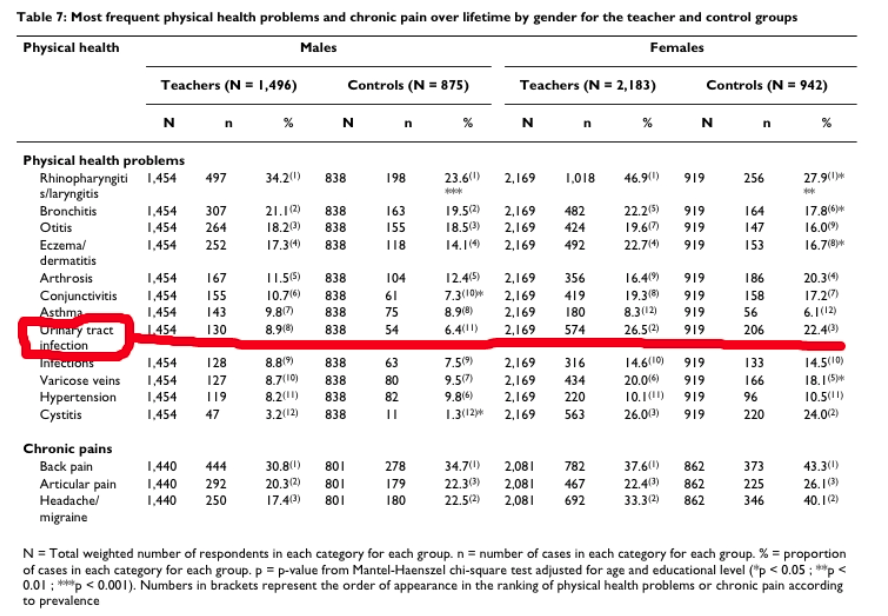

Since Rabbi Yochanan described prophecy as being given to those with mental illness, it might be worth looking at the content of some hallucinations in the Jewish mentally ill. Is there anything in their hallucinations that we could perhaps interpret as prophecy? Let's turn to a helpful paper published in 2001, which described the nocturnal hallucinations in 122 ultra-orthodox Jewish Israeli men. The authors were two psychiatrists who noted that this symptom of nocturnal hallucinations only seemed to affect male members of the ultra-orthodox population. The group who experienced these nocturnal hallucinations were younger than other patients with symptoms of mental illness, "and their visit was more often associated with a request for a psychiatric evaluation before receiving an exemption from compulsory army service." But let's put that rather disquieting fact aside, and move on. The majority of the hallucinations were frightening, and included figures of the sort that "may appear among the fears of ultra-orthodox men," including (and I'm not making this up) "policemen, soldiers [and] Sephardi men."

From Greenberg D. Brome, D. Nocturnal Hallucinations in Ultra-orthodox Jewish Israeli Men. Psychiatry 2001. 64 (1); 81-90.

Now you might be thinking that this group included a fair number of malingerers who were keen to avoid military service. The psychiatrists considered that possibility too, but noted that about 45% of the men came for more than one visit, and about 11% did not not request a recommendation letter for the army. So they concluded that "the night hallucinations are a real clinical and culturally determined phenomenon, which in a minority of cases may have been misused and presented for purposes of gaining exemption from army service." In any event, most ended up with a diagnosis of "subnormality and/or psychosis," with a generally good prognosis. But there is nothing that appears to be particularly prophetic in the thoughts of this group of mentally ill Jewish men.

“We suggest that some of civilization’s most significant religious figures may have had psychotic symptoms that contributed inspiration for their revelations. It is hoped that this analysis will engender scholarly dialogue about the rational limits of human experience and serve to educate the general public, persons living with mental illness, and healthcare providers about the possibility that persons with primary and mood disorder-associated psychotic-spectrum disorders have had a monumental influence on civilization.”

On the origin of prophecy today

In his seventeenth century commentary on the Talmud, R. Samuel Eliezer ben R. Judah HaLevi Edels, better known as the Maharsha, suggests that there are different kinds of prophecy.

מהרש"א חידושי אגדות מסכת בבא בתרא דף יב עמוד ב

וענין שנטלה מן הנביאים ונתנה לשוטים אין הנבואות שוות דנבואת נביאים ע"י הש"י או ע"י מלאכיו אבל נבואת השוטים ותינוקות אינו אלא ע"י שד דהכי מחלק בפרק הרואה בין החלומות שיש מהן ע"י המלאך ויש מהן ע"י שד

"Not all prophecy is the same. For the prophecy of the prophets was endowed by God, Blessed be He, or one of His angels, whereas the prophecy of the mentally ill and children is endowed by a demon..."

Which may only serve to scare the mentally ill even more. R. Yochanan's statement reminds us that the line between mental disease and religiously inspired hallucinations (or delusions) is very blurred, and that, whatever the source of their visions and hallucinations, the mentally ill deserve more than our pity or support. They deserve our respect.

“If you hear a car backfire and you believe that it may be a pistol shot, that is an illusion. If you hear a pistol shot when there has been no sound (either of a pistol or a car backfiring), that is a hallucination. If you hear a pistol shot and believe that it is God firing a pistol at you because you [as a physician] have ordered inappropriate lab tests, that is a delusion. If [a physician] decides he is ordering too many laboratory tests in the absence of an external sensory stimulus, that is called enlightenment.”