בבא מציעא ב,ב

שנים אוחזין בטלית ... זה אומר כולה שלי וזה אומר חציה שלי ...זה נוטל שלשה חלקים וזה נוטל רביע

Two hold a garment; ... one claims it all, the other claims half. ... Then the one is awarded 3⁄4, the other 1⁄4.

We open the new masechet of Bava Metzia with two people claiming ownership of a garment. One claims that it belongs entirely to her, and the other claims he owns half of the garment. In this case, the Mishnah rules that each swears under oath, and then the garment is divided with 3/4 awarded to one claimant and 1/4 to the other.

Rashi and the Principal of Contested Sums

In his explanation of our Mishnah, Rashi notes that the claimant to half the garment concedes that half belongs to the other claimant, so that the dispute revolves solely around the second half. Consequently, each of them receives half of this disputed half - or a quarter each.:

זה אומר חציה שלי. מודה הוא שהחצי של חבירו ואין דנין אלא על חציה הלכך זה האומר כולה שלי ישבע כו' כמשפט הראשון מה שהן דנין עליו נשבעין שניהם שאין לכל אחד בו פחות מחציו ונוטל כל אחד חציו

Now of course this is only one way that the garment could be divided between the two claimants. For example, it could be divided in proportion to the two claims, (2/3-1/3), or even split evenly (1/2-1/2). But instead, and as Rashi explained, the Mishnah ruled using the principal of contested sums. Which is where Robert Aumann comes in.

Game Theory from Israel's Nobel Prize Winner

We have met Robert Aumann before, when we reviewed Israel's glorious winners of the Nobel Prize. For those who need reminding, Aumanm, from the Hebrew University, won the 2005 Nobel Prize in Economics. His work was on conflict, cooperation, and game theory (yes, the same kind of game theory made famous by the late John Nash, portrayed in A Beautiful Mind). Aumann worked on the dynamics of arms control negotiations, and developed a theory of repeated games in which one party has incomplete information. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences noted that this theory is now "the common framework for analysis of long-run cooperation in the social science." The kippah-wearing professor opened his speech at the Nobel Prize banquet with the following words (which were met with cries of אמן from some members of the audience):

ברוך אתה ה׳ אלוקנו מלך העולם הטוב והמיטב

If you haven't already seen it, take the time to watch the four-minute video of his acceptance speech. It should be required viewing for every Jewish high school student (and their teachers).

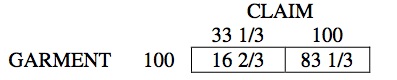

Where was I? Oh, yes. Contested sums. In 1985, twenty years before receiving his Nobel Prize, Aumann described the theoretic underpinnings of today's Mishnah, as part of a larger discussion about bankruptcy. His paper, published in the Journal of Economic Theory, is heavy on mathematical notations and light on explanations for non-mathematicians (like me). Fortunately he later published a paper that is much easier to read and which covers the same material. The second paper appeared in the Research Bulletin Series on Jewish Law and Economics, published by Bar-Ilan University in June 2002. "Half the garment" wrote the professor, "is not contested: There is general agreement that it belongs to the person who claimed it all. Hence, first of all, that half is given to him. The other half, which is claimed by both, is then divided equally between the claimants, each receiving one-quarter of the garment." Here is how Aumann visualizes it:

There is another example of this from the Tosefta, a supplement to the Mishnah and contemporary with it. In this new case, one person claims the entire garment, and one claims only one third of it. In this case, the first person gets 5/6 and the second gets 1/6.

Aumann calls this principal the "Contested Garment Consistent." It turns out that this principal is found in other contested divisions, like a case in Ketuvot 93a, in which a man dies, leaving debts totaling more than his estate. The Mishnah explains how the estate should be divided up among his three wives, each of who has a claim. And it uses the same principal as the one found in today's Mishnah: the Contested Garment Consistent.

משנה, כתובות צג, א

מי שהיה נשוי שלש נשים ומת כתובתה של זו מנה ושל זו מאתים ושל זו שלש מאות ואין שם אלא מנה חולקין בשוה

היו שם מאתים של מנה נוטלת חמשים של מאתים ושל שלש מאות שלשה שלשה של זהב

היו שם שלש מאות של מנה נוטלת חמשים ושל מאתים מנה ושל שלש מאות ששה של זהב

If a man who was married to three wives died, and the kethubah of one was a maneh (one hundred zuz), of the other two hundred zuz, and of the third three hundred zuz, and the estate was worth only one maneh (one hundred zuz), they divide it equally.

If the estate was worth two hundred zuz, the claimant with the kesuva of the maneh receives fifty zuz, while the and the claimants of the two hundred and the three hundred zuz each receive three gold denarii (worth seventy-five zuz).

If the estate was worth three hundred zuz, the claimant of the maneh receives fifty zuz, the claimant of the two hundred zuz receives a maneh (one hundred zuz) and the the claimant of the three hundred zuz receives six gold denarii (worth one hundred and fifty zuz)…

Aumann likes to think of it this way:

Here is how he explains what is going on in the Mishnah in Ketubot.

We’ll call the creditor with the 100-dinar claim “Ketura,” the one with the 200, “Hagar” and the one with the 300, “Sara.” Let’s assume, to begin with, that the estate is 200. As per [the table above], Ketura gets 50 and Hagar 75 – together 125. On the principle of equal division of the contested sum, the 125 gotten by Hagar and Ketura together should be divided between them in keeping with this principle. ... In other words, the Mishna’s distribution reflects a division of the sum that Hagar and Ketura receive together according to the principle of equal division of the contested sum...

The division of the estate among the three creditors is such that any two of them divide the sum they together receive, according to the principle of equal division of the contested sum. This precisely is the method of division laid down in the Mishna in Bava Metzia that deals with the contested garment.

There's a lot more to the paper, including an interesting proof of the principal using fluids poured into cups of different sizes. But I prefer to focus on another aspect of the paper. Prof. Aumann notes that, in addition to its own internal logic, the underlying principal of contested sums fits in well with other talmudic passages.

The reader may ask, isn’t it presumptuous for us to think that we succeeded in unraveling the mysteries of this Talmudic passage, when so many generations of scholars before us failed? To this, gentle reader, we respond that the scholars who studied and wrote about this passage over the course of almost two millennia were indeed much wiser and more learned than we. But we brought to bear a tool that was not available to them: the modern mathematical theory of games.

The actual sequence of events was that we first discovered that the Mishnaic divisions are implicit in certain sophisticated formulas of modern game theory. Not believing that the sages of the Talmud could possibly have been aware of these complex mathematical tools, we sought, and eventually found, a conceptual basis for these tools: the principle of consistency. Of this, the sages could have been, and presumably were, aware. It in itself is sufficient to yield the Mishnaic divisions; and it is this principle that we describe below, bypassing the intermediate step – the game theory.

It’s like “Alice in Wonderland.” The game theory provides the key to the garden, which Alice had such great difficulty in obtaining. Once in the garden, though, Alice can discard the key; the garden can be enjoyed without it.

What a wonderful analogy. Game theory is the key to entering the garden, a key which might not have been available to earlier generations who learned the Talmud. How lucky we are.