To the naked eye, the terrain of the Earth varies quite distinctly; in some places it is fairly flat, while in others it is mountainous and irregular. Standing and looking out over the sea, the water appears perfectly smooth and continues as far as the eye could see. What is beyond that was often unknown in the ancient world, and what supported the Earth itself could only be ascertained from reading the Bible. Of the few sages whose cosmology is known to us, one of the most important was Rabbi Yose ben Halafta. Born in Lower Galilee some time in the middle of the second century, Rabbi Yose was a student of the famous Rabbi Akiva, and he went on to establish a rabbinic court in his hometown of Zippori (Sepphoris). Although most of his teachings were legal in nature, he also addressed the geographic locations of both the Earth and God in the universe on today’s page of Talmud:

חגיגה יב, ב

תַּנְיָא, רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: אוֹי לָהֶם לַבְּרִיּוֹת, שֶׁרוֹאוֹת, וְאֵינָן יוֹדְעוֹת מָה רוֹאוֹת. עוֹמְדוֹת, וְאֵין יוֹדְעוֹת עַל מָה הֵן עוֹמְדוֹת. הָאָרֶץ עַל מָה עוֹמֶדֶת — עַל הָעַמּוּדִים, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״הַמַּרְגִּיז אֶרֶץ מִמְּקוֹמָהּ וְעַמּוּדֶיהָ יִתְפַלָּצוּן״. עַמּוּדִים, עַל הַמַּיִם — שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״לְרוֹקַע הָאָרֶץ עַל הַמָּיִם״. מַיִם, עַל הֶהָרִים — שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״עַל הָרִים יַעַמְדוּ מָיִם״. הָרִים, בְּרוּחַ — שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״כִּי הִנֵּה יוֹצֵר הָרִים וּבוֹרֵא רוּחַ״. רוּחַ, בִּסְעָרָה — שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״רוּחַ סְעָרָה עוֹשָׂה דְבָרוֹ״. סְעָרָה, תְּלוּיָה בִּזְרוֹעוֹ שֶׁל הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא — שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וּמִתַּחַת זְרוֹעוֹת עוֹלָם״

It is taught in a baraita: Rabbi Yose says: Woe to them, the creations, who see and know not what they see; who stand and know not upon what they stand. He clarifies: Upon what does the earth stand? Upon pillars, as it is stated: “Who shakes the earth out of its place, and its pillars tremble” (Job 9:6). These pillars are positioned upon water, as it is stated: “To Him Who spread forth the earth over the waters” (Psalms 136:6). These waters stand upon mountains, as it is stated: “The waters stood above the mountains” (Psalms 104:6). The mountains are upon the wind, as it is stated: “For behold He forms the mountains and creates the wind” (Amos 4:13). The wind is upon a storm, as it is stated: “Stormy wind, fulfilling His word” (Psalms 148:8). The storm hangs upon the arm of the Holy One, Blessed be He, as it is stated: “And underneath are the everlasting arms”(Deuteronomy 33:27), which demonstrates that the entire world rests upon the arms of the Holy One, Blessed be He.

It is of course entirely reasonable to suggest a metaphoric explanation for this cosmology and to suggest that this talmudic discussion not be taken literally. This approach would seem to be supported by an opposing cosmology suggested by those who take issue with Rabbi Yose’s picture:

וַחֲכָמִים אוֹמְרִים: עַל שְׁנֵים עָשָׂר עַמּוּדִים עוֹמֶדֶת, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״יַצֵּב גְּבוּלוֹת עַמִּים לְמִסְפַּר בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל״. וְיֵשׁ אוֹמְרִים: שִׁבְעָה עַמּוּדִים, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״חָצְבָה עַמּוּדֶיהָ שִׁבְעָה״. רַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר בֶּן שַׁמּוּעַ אוֹמֵר: עַל עַמּוּד אֶחָד, וְצַדִּיק שְׁמוֹ, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וְצַדִּיק יְסוֹד עוֹלָם״

And the Rabbis say: The earth stands on twelve pillars, as it is stated: “He set the borders of the nations according to the number of the children of Israel” (Deuteronomy 32:8). Just as the children of Israel, i.e., the sons of Jacob, are twelve in number, so does the world rest on twelve pillars. And some say: There are seven pillars, as it is stated: “She has hewn out her seven pillars” (Proverbs 9:1). Rabbi Elazar ben Shammua says: The earth rests on one pillar and a righteous person is its name, as it is stated: “But a righteous person is the foundation of the world”(Proverbs 10:25).

This single pillar suggested by Rabbi Eleazar certainly seems to be metaphoric rather than literal, given the context of the surrounding verses of the Book of Proverbs from which it is taken. A metaphorical understanding, however, does not fit in with the rest of the discussion. For, having established what lies beneath the Earth, the Talmud then addresses the nature of the skies above it and records the precise order and number of layers of the heavens. This technical discussion is generally not understood as being merely a metaphor. For example, it is this passage that is used by Maimonides to establish his own cosmology. In light of this, it is reasonable to assume that Rabbi Yose’s claim that the Earth rests on pillars that are supported by God is his description of reality.

The Rabbinic Flat Earth

Whether it stood on seven pillars or only one, the Earth was considered by the sages of the Talmud to be flat. As recorded in the Jerusalem Talmud, people lived on this flat Earth completely surrounded by water:

ירושלמי עבודה זרה3:1

אָמַר רִבִּי יוֹנָה. אַלֶכְּסַנְדְּרוֹס מַקֶּדוֹן כַּד בְּעָא מֵיסַק לְעֵיל. וַהֲיָה סְלַק וּסְלַק סְלַק עַד שֶׁרָאָה אֶת הָעוֹלָם כַּכַּדּוּר וְאֶת הְיָּם כִּקְעָרָה. בְּגִין כֵּן צַּייְרִין לֵהּ בְּכַדּוּרָה בְיָדֵהּ. וִיצוּרֶינָּה קְעָרָה בְיָדֵהּ. אֵינוּ שַׁלִּיט בַּיָּם. אֲבָל הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא שַׁלִּיט בַּיָּם וּבַיַּבָּשָׁה. מַצִּיל בַּיָּם וּמַצִּיל בַּיַבָּשָׁה

Rebbi Yonah said, when Alexander the Macedonian wanted to ascend he rose, and rose, and rose, until he saw the Earth as a ball and the ocean like a plate

“The opinion of our sages of blessed memory in these matters is well known: They believed that the Earth and the Great Ocean were flat.”

Another talmudic sage, Rabbi Natan, noted that the stars do not seem to change in their positions overhead when walking far distances. The assumption underlying his explanation for this observation was that the Earth is flat. Covering this flat Earth was an opaque cap referred to as the rakia, which is most commonly translated as the sky or firmament. Rava, a fourth-century Babylonian sage who lived on the banks of the river Tigris, determined this cap to be 1,000 parsa in width, while Rabbi Yehudah thought that he had over- estimated this thickness. There were others who added to the picture of the sky; on today’s page of Talmud Resh Lakish announced that it actually was made up of seven distinct layers.

חגיגה יב, ב

רֵישׁ לָקִישׁ אָמַר: שִׁבְעָה, וְאֵלּוּ הֵן: וִילוֹן, רָקִיעַ, שְׁחָקִים, זְבוּל, מָעוֹן, מָכוֹן, עֲרָבוֹת. וִילוֹן — אֵינוֹ מְשַׁמֵּשׁ כְּלוּם, אֶלָּא נִכְנָס שַׁחֲרִית וְיוֹצֵא עַרְבִית, וּמְחַדֵּשׁ בְּכׇל יוֹם מַעֲשֵׂה בְרֵאשִׁית, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״הַנּוֹטֶה כַדּוֹק שָׁמַיִם וַיִּמְתָּחֵם כָּאֹהֶל לָשָׁבֶת״. רָקִיעַ — שֶׁבּוֹ חַמָּה וּלְבָנָה כּוֹכָבִים וּמַזָּלוֹת קְבוּעִין, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וַיִּתֵּן אוֹתָם אֱלֹהִים בִּרְקִיעַ הַשָּׁמָיִם״. שְׁחָקִים — שֶׁבּוֹ רֵחַיִים עוֹמְדוֹת וְטוֹחֲנוֹת מָן לַצַּדִּיקִים, שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: ״וַיְצַו שְׁחָקִים מִמָּעַל וְדַלְתֵי שָׁמַיִם פָּתָח. וַיַּמְטֵר עֲלֵיהֶם מָן לֶאֱכוֹל וְגוֹ׳״

Reish Lakish said:There are seven firmaments, and they are as follows: Vilon, Rakia, Shechakim, Zevul, Ma’on, Makhon, and Aravot.The Gemara proceeds to explain the role of each firmament: Vilon, curtain, is the firmament that does not contain anything, but enters at morning and departs in the evening, and renews the act of Creation daily, as it is stated: “Who stretches out the heavens as a curtain [Vilon], and spreads them out as a tent to dwell in” (Isaiah 40:22). Rakia, firmament, is the one in which the sun, moon, stars, and zodiac signs are fixed, as it is stated: “And God set them in the firmament [Rakia] of the heaven” (Genesis 1:17). Shechakim, heights, is the one in which mills stand and grind manna for the righteous, as it is stated: “And He commanded the heights [Shehakim] above, and opened the doors of heaven; and He caused manna to rain upon them for food, and gave them of the corn of heaven” (Psalms 78:23–24).

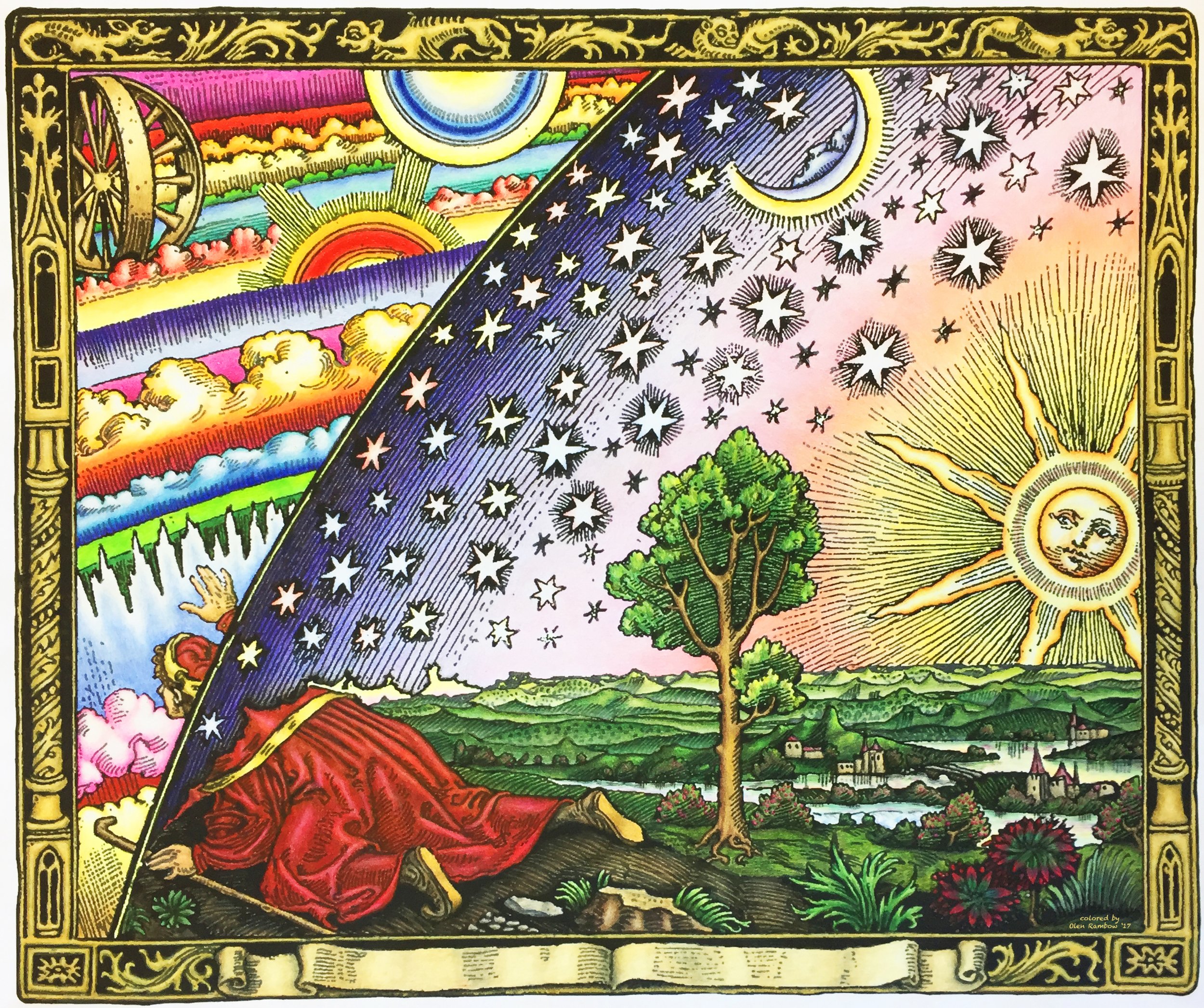

Given this model, there would have to be a place where the opaque cap touched the Earth, and Rabba bar Bar Hanah in fact claimed to have touched this Earth-sky interface:

בבא בתרא עד, א

אָמַר לִי תָּא אַחְוֵי לָךְ הֵיכָא דְּנָשְׁקִי אַרְעָא וּרְקִיעָא אַהֲדָדֵי שְׁקַלְתָּא לְסִילְתַּאי אַתְנַחְתָּא בְּכַוְּותָא דִרְקִיעָא אַדִּמְצַלֵּינָא בְּעֵיתֵיהּ וְלָא אַשְׁכַּחְתֵּהּ אָמֵינָא לֵיהּ אִיכָּא גַּנָּבֵי הָכָא אֲמַר לִי הַאי גִּלְגְּלָא דִרְקִיעָא הֲוָה דְּהָדַר נְטַר עַד לִמְחַר הָכָא וּמַשְׁכַּחַתְּ לַהּ

A certain Arab also said to me: Come, I will show you the place where the earth and the heavens touch each other. I took my basket and placed it in a window of the heavens. After I finished praying, I searched for it but did not find it. I said to him: Are there thieves here? He said to me: This is the heavenly sphere that is turning around; wait here until tomorrow and you will find it.

The Flammarion Engraving, from here.

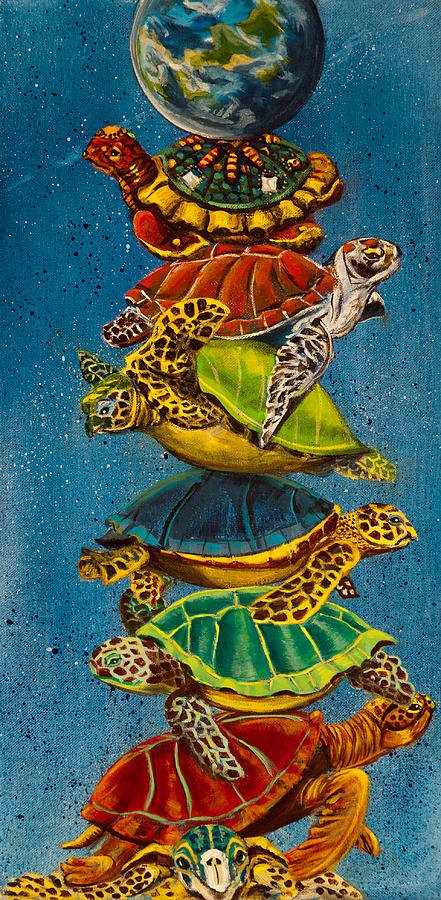

Turtles all the way down

In classic Jewish teaching, the Earth rests on twelve pillars. Or seven. Or just one. Other cultures have their own cosmology myths, of which perhaps the most well-known is a story in which the world is carried on the back of a turtle. Here is a version told by the Delaware “Indians” (or native Americans, as we would call them today):

First there was only water, then the Great Turtle gradually rose above water level, and the Creator placed mud on his shell. The mud dried and the Great Tree grew in the middle of the earth. As the Tree grew towards the sky a sprout became a man, then the great Tree bent down and in touching the earth caused a sprout to become a woman. From this man and woman all of humanity descended.

Susan Culver. Turtles All The Way Down, from here.

The belief that the Earth rests on the back of a Turtle is apparently also shared by the Iroquois, and when the turtle moves, there are earthquakes. In Hindu belief, Kurma is a turtle incarnation of the God Vishnu. This incarnation is also known as Akupara (Sanskrit: अकूपार), and it supports the world on its back. The earliest reference to the myth in Western literature is from the Jesuit Emanuel da Veiga (1549–1605), who described it in a letter written in 1599:

Others hold that the earth has nine corners by which the heavens are supported. Another disagreeing from these would have the earth supported by seven elephants, and the elephants do not sink down because their feet are fixed on a tortoise. When asked who would fix the body of the tortoise, so that it would not collapse, he said that he did not know.

In Chinese mythology, Ao is a turtle whose legs were chopped off by the goddess Nuwa and used them to support the sky. “It’s not quite carrying the world on its back,” wrote Eric Grundhauser on the site Atlas Obscura, “but it still puts a terrapin at the center of the universe, making sure that the very sky doesn’t fall down.”

The obvious question is, on what does the turtle that is supporting the world stand? And the answer is: another turtle, of course. It is “turtles, all the way down,” a phrase that has come to mean infinite regress. Here is how the late great physicist Steven Hawking told the story in his bestselling book A Brief History of Time:

A well-known scientist (some say it was Bertrand Russell) once gave a public lecture on astronomy. He described how the earth orbits around the sun and how the sun, in turn, orbits around the centre of a vast collection of stars called our galaxy. At the end of the lecture, a little old lady at the back of the room got up and said: "What you have told us is rubbish. The world is really a flat plate supported on the back of a giant tortoise." The scientist gave a superior smile before replying, "What is the tortoise standing on?" "You're very clever, young man, very clever," said the old lady. "But it's turtles all the way down!"

To avoid its own infinite regress, Rabbi Yose imagined that world rested on pillars, which rested on water, which rested on mountains, which rested on the wind, which rested on a storm, which rested on the arms of God. It wasn’t turtles all the way down, as it was for some other cultures. It had an end, and the end was God.

Want more on rabbinic cosmology? Try these posts: