In today’s page of Talmud there is an interesting discussion of how to dissipate the intoxicating properties of alcohol:

תענית יז ,ב

דְּאָמַר רָמֵי בַּר אַבָּא: דֶּרֶךְ, מִיל, וְשֵׁינָהכל שֶׁהוּא — מְפִיגִין אֶת הַיַּיִן! לָאו מִי אִיתְּמַר עֲלַהּ, אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן אָמַר רַבָּה בַּר אֲבוּהּ: לֹא שָׁנוּ אֶלָּא בְּשֶׁשָּׁתָה שִׁיעוּר רְבִיעִית, אֲבָל שָׁתָה יוֹתֵר מֵרְבִיעִית — כל שֶׁכֵּן שֶׁדֶּרֶךְ מַטְרִידָתוֹ וְשֵׁינָה מְשַׁכַּרְתּוֹ

Rami bar Abba said: Walking a distance of a mil, and similarly, sleeping even a minimal amount, will dispel the effect of wine that one has drunk. But wasn’t it stated about this halakha that Rav Nahman said that Rabba bar Avuh said: They taught this only with regard to one who has drunk the measure of a quarter-log of wine, but with regard to one who has drunk more than a quarter-log, walking this distance will preoccupy and exhaust him all the more, and a small amount of sleep will further intoxicate him.

How alcohol is metabolized

Alcohol, or really ethanol ,which is the specific kind of alcohol found in our alcoholic drinks, is metabolized in the liver. This is why, if you drink too much of it for too long, you will irreversibly damage that organ. The liver first breaks down ethanol into acetaldehyde; that is then broken down into acetic acid and a molecule called acetyl coenzyme, or acetyl-CoA. Once acetyl-CoA is formed, it is further used in the citric acid cycle, ultimately producing cellular energy and releasing water and carbon dioxide.

The amount of ethanol that the liver can break down per hour varies greatly between individuals. Here are some of the factors at play:

Gender

Men and women generally have similar alcohol elimination rates when results are expressed as grams per hour, but per unit of lean body mass, women are faster at breaking down ethanol.

Age

As we age we get slightly slower at eliminating ethanol.

Race

Native American men and women appear to eliminate alcohol faster than whites. There is also evidence that people of Asian descent have a slightly faster rate of metabolism, owing to a polymorphism in the Class I hepatic ADH enzyme. But overall, racial and ethnic differences in rates of ethanol elimination are small compared with many other factors.

Alcoholism

Heavy drinking increases alcohol metabolic rate. But advanced liver disease will decrease the rate of ethanol metabolism.

Nutritional state

Alcohol metabolism is slower in people with a poor nutritional state. Kinda like drinking on an empty stomach.

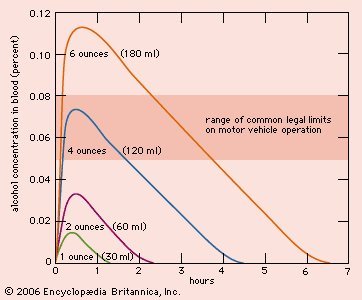

Here is the bottom line. Although rates vary widely, the “average” metabolic capacity to remove alcohol is about 7 gm/hr which translates to about one drink per hour. In the graph below, you can see the blood alcohol concentration in an average man at hourly intervals after drinking one, two, four, or six ounces of spirits containing 50 percent alcohol. A person who drink alcohol frequently might metabolize his drinks more quickly, because (among other things) alcohol induces the production of more alcohol dehydrogenase, which is needed to break alcohol down. Conversely, a person who rarely drinks might metabolize it more slowly. This is the reason that when I worked in the emergency department, it was the young drunks, especially those of college age, who worried me more than the older, chronic drunks. The chronic drinkers will metabolize their alcohol much faster.

Image from here.

Another measure to remember is that in general, the elimination rate is around 10-15mg/dL/hr in alcohol naive people and around 20mg/dL/hr or higher in those with chronic alcohol use. Try as you might, there is really nothing you can do to speed up this rate of elimination. Which brings us to…

Exercise and alcohol metabolism

According to Rami bar Abba on today’s page of Talmud, exercise can increase the elimination of alcohol.

אמר רמי בר אבא דרך מיל ושינה כל שהוא מפיגין את היין

Rami bar Abba said: Walking a path of a mil, and similarly, sleeping even a minimal amount, will dispel the effect of wine that one has drunk.

Does exercise help, as Rami bar Abba suggested? Well, there is one study that looked at this very question. It studied rats, which were fed alcohol mixed into their liquid diet “with use of a kitchen wire whisk and bowl.” They were then made to run on a little rodent treadmill, and blood was removed from their tails at various time intervals. The researchers, from the University of Texas at Austin, concluded that “…running exercise for periods of at least 60 min will increase rates of ethanol clearance compared with rates measured at rest.” So if you are a rat with a hangover, a vigorous run for an hour might help you feel better. But what about us?

Well, it depends how much you exert yourself. A study published in 1982 tested the rates of alcohol elimination in a very small group of volunteers, who got drunk and hopped on an exercise bike. It found that

prolonged physical exercise produces an enhanced ethanol elimination if the intensity and duration of exercise are sufficient. But this finding has hardly any pathological meaning.The reasons for the enhanced elimination of blood alcohol are probably to be found in the elevated body temperature caused by physical exercise and in a supplementary loss of alcohol by perspiration and exhalation. The muscles are not able to utilize ethanol either directly or indirectly.

TIME-DEPENDENT ELIMINATION OF ALCOHOL

Sleep does nothing to speed up the metabolism of alcohol either. But what if Rami bar Abba was not suggesting an activity, but rather a length of time? Perhaps he is in effect saying that the alcohol wears off in about the time it takes to walk a mil, or have a short nap. That certainly makes physiological sense. To which Rav Nachmun pointed out that this time period only applied after a small amount of wine (“a quarter log”). Any more than that could not be eliminated in such a short period. Also physiologically correct.

But as Rami bar Avuha (not the same Rami as before) noted, if you are really intoxicated, you would need more time to sober up.

אָמַר רַב נַחְמָן אָמַר רַבָּה בַּר אֲבוּהּ: לֹא שָׁנוּ אֶלָּא שֶׁשָּׁתָה כְּדֵי רְבִיעִית, אֲבָל שָׁתָה יוֹתֵר מֵרְבִיעִית — כל שֶׁכֵּן שֶׁדֶּרֶךְ טוֹרַדְתּוֹ וְשֵׁינָה מְשַׁכַּרְתּוֹ

Rav Nachman said that Rabba bar Avuh said: They only taught this with regard to one who has drunk a quarter-log of wine, but with regard to one who has drunk more than a quarter-log, this advice is not useful. In that case, walking a path of such a distance will preoccupy and exhaust him all the more, and a small amount of sleep will further intoxicate him.

Of course so long as you stop drinking, there is no way that a nap will further raise your alcohol level, but again, if you have consumed a lot of alcohol and take a nap, you may wake with an awful hangover, which may make you feel as if you were intoxicated.

How to drink the Four Cups of Wine at the Seder

In tractate Shekalim there is a lengthy excursus into the laws of the Four Cups of wine that must be drunk on the night of the Seder. May one drink the four cups little by little, sip by sip, or must they be drunk in large gulps?

שקלים ח, ב

מָהוּ לִשְׁתוֹתָן בְּפִיסָקִין. כְּלוּם אָֽמְרוּ שֶׁיִּשְׁתּוּ לוֹ כְּדֵי שֶׁיִּשְׁתַּנֶּה וְלֹא יִשְׁתַּכֵּר. אִם שָׁתָה בְפִסָקִין אַף הוּא אֵינוֹ מִשְׁתַּכֵּר

What is the halakha with regard to drinking the four cups of wine little by little, with interruptions? The Gemara answers: When the Sages said that one must drink four cups of wine, didn’t they institute that he must drink them, and not that he should become intoxicated from drinking them? Therefore, if he drank them little by little, with intervals, he too is acting in accordance with the will of the Sages, as he is not becoming intoxicated, and therefore he need not drink the entire quarter-log at once.

In other words, because the rabbis specifically wanted to avoid the Seder celebrants becoming intoxicated, they did not allow additional wine to be drunk between the Third and Fourth cups of wine. Hence, the Talmud concludes that sipping wine a little at a time is certainly permitted. And now that we have reviewed the way in which alcohol is metabolized, this ruling makes physiological sense. You are less likely to become intoxicated if you sip your cup slowly over some time, rather than finish it in one or two gulps. It’s all about the alcohol dehydrogenase.

On the other effects of alcohol

The Talmud has a few conflicting statements about wine and its intoxicating effects. In another tractate (Eruvin 65a) Rav Chaninah claimed that the relaxed feeling a person gets after drinking wine puts him in the same mindset as the Creator of the universe:

אמר רבי חנינא כל המתפתה ביינו יש בו מדעת קונו שנאמר וירח ה׳ את ריח הניחוח וגו׳

Rabbi Chanina said: Whoever is appeased by his wine, i.e., whoever becomes more relaxed after drinking, has in him an element of the mind-set of his Creator, who acted in a similar fashion, as it is stated: “And the Lord smelled the sweet savor, and the Lord said in His heart, I will not again curse the ground any more for man’s sake” (Genesis 8:21).

And according to Rav Chanan bar Papa, it is a sign of prosperity if “wine flows like water” in the house (Eruvin 65a).

But rabbis also pointed out the dangers of drinking to excess. One explanation for the deaths of the sons of Aaron the High Priest (described in Lev.10) is that they were drunk when they performed in the Mishkan. Elsewhere we have discussed how the Talmud described alcoholic liver disease, and how it precluded a Cohen from service in the Temple. Like many things, wine should be taken in moderation. That lesson, taught in Avot D’Rabbi Natan, was true in talmudic times, and remains so in ours too.

אבות דרבי נתן 37:5

ח׳ דברים רובן קשה ומיעוטן יפה. יין מלאכה שינה ועושר ודרך ארץ ומים חמין והקזת דם

There are eight things which are dangerous in excess but good in moderation: wine, work, sleep, [having] wealth, sexual relations, [bathing in] hot water, and bloodletting.

Want more? Here are some other Talmudology posts that also discuss alcohol and its effects:

Cohanim and alcoholic liver disease

The healing effects of alcohol

Alcohol and cognitive function