Yesterday, we learned in a Mishnah that the quality of a shofar may be improved by immersing it in wine or water. Today, we continue with this theme.

ראש השנה לד, א

וְאֵין חוֹתְכִין אוֹתוֹ — בֵּין בְּדָבָר שֶׁהוּא מִשּׁוּם שְׁבוּת, וּבֵין בְּדָבָר שֶׁהוּא מִשּׁוּם לֹא תַעֲשֶׂה. אֲבָל אִם רָצָה לִיתֵּן לְתוֹכוֹ מַיִם אוֹ יַיִן — יִתֵּן

And one may not cut the shofar to prepare it for use, neither with an object that is prohibited due to a rabbinic decree nor with an object that may not be used due to a prohibition by Torah law. However, if one wishes to place water or wine into the shofar on Rosh HaShana so that it emits a clear sound, he may place it, as this does not constitute a prohibited labor.

אֲבָל אִם רָצָה לִיתֵּן לְתוֹכוֹ מַיִם אוֹ יַיִן — יִתֵּן. מַיִם אוֹ יַיִן — אֵין, מֵי רַגְלַיִם — לָא

The Mishna continues. However, if one wishes to place water or wine into the shofar on Rosh HaShana, so that it should emit a clear sound, he may place it.The Gemara infers: Water or wine, yes, one may insert these substances into a shofar. However, urine, no.

So the Mishnah rules that a shofar may be bathed in water and wine because it helps to emit a clear sound. But urine may not be used to improve the quality of the shofar, because, as Abba Shaul goes on to teach

מֵי רַגְלַיִם — אָסוּר, מִפְּנֵי הַכָּבוֹד

With regard to water or wine, one is permitted to pour these liquids into a shofar on Rosh HaShana in order to make its sound clear. However, with regard to urine, one is prohibited to do so due to the respect that must be shown to the shofar. Although urine is beneficial, it is disrespectful to place it in a shofar, which serves for a mitzva.

Fair enough. But Abba Shaul’s lesson is just the beginning of the story of the beneficial properties of urine for the Temple service, and for people too.

From here.

We don’t bring Urine into the Azarah (Courtyard)

In the famous Mishnah known as Pittum Haketoret with describes the preparation of the incense in the Temple, there is a complicated list of eleven ingredients. And then comes this:

יֵין קַפְרִיסִין שֶׁשּׁוֹרִין בּוֹ אֶת הַצִּפּוֹרֶן. כְּדֵי שֶׁתְּהֵא עַזָּה. וַהֲלֹא מֵי רַגְלַיִם יָפִין לָהּ, אֶלָּא שֶׁאֵין מַכְנִיסִין מֵי רַגְלַיִם בַּמִּקְדָּשׁ מִפְּנֵי הַכָּבוֹד׃

Why was Cyprus wine employed? To steep the onycha in it so as to make it more pungent. Though urine might have been suitable for that purpose, it was not decent to bring it into the Temple.

This Mishnah, recited every day by most Sephardim (and many Ashkenazi services in Israel) explains that like its use for the shofar, urine was good at improving the quality of some Temple accessories, but, regardless, “it’s not decent to bring it into Temple” for that purpose. So just what are the properties of urine that make it sometimes useful?

The Properties of Urine

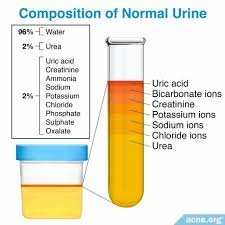

The vast majority of urine (90-96%) is made up of water, with the remainder made of organic and inorganic salts, and urea. That last one, urea, is very important. Urea, which comes from the breakdown of proteins, is by itself odorless and colorless, but is a terrific fertilizer. Over time, however, the urea is further broken down in ammonia and other compounds, which give older, stale urine its characteristic odor. And there is a long tradition of using urine to improve lots of things, including, it turns out, our health.

Sefer Moshia Hosim

The Italian Jew Abraham ben Hananiah Yagel (1553- c.1624) was by any definition a polymath. His works include not one but two lengthy encyclopedias, a manual of belief “audaciously adapted from a Catholic manual” and a work in praise of women. But Yagel was first and foremost a physician, and it was in this role that in 1587 he published his first work, a short tract on plagues called Moshia Hosim (The Savior of Those Who Seek Refuge).

Moshia Hosim opens with a declaration that was both theological and medical: “Every wise person knows that reality is divided into three realms: the elementary, the divine, and the intellectual. Every part of the lower world is moved and influenced by the upper, as the rabbis stated in Bereshit Rabbah: There is no blade of glass that sways without having been controlled by a constellation that directs it to grow.” The origins of any plague therefore depended on the precise interactions of these three realms. The stars and constellations would cause the release of foul, poisonous air, “for nothing happens on earth without the influence of the heavens.”

While some plague were a divine punishment for sin, these were of a fundamentally different nature from others. Divinely sent plagues stuck suddenly and left no physical mark on their victim, unlike “naturally” occurring outbreaks. But whatever their celestial origins, certain groups like women and children were more vulnerable because of their humoral imbalance, as were naturally good-looking young adults. Yagel, like most of his medical contemporaries, understood that whatever agent it was that caused a plague, it could be transmitted through close physical contact. He cited the actions of three Talmudic sages who would be careful to avoid being bitten by flies during a pandemic, or who would not share food or close contact with a victim “for flies and birds transmit sickness from person to person.” Yagel prescribed a diet free of rich foods and avoiding sexual intercourse, both of which led to the dangerous condition of overheating. He also recommended theriac, a medieval concoction of herbs that was thought to be an antidote to all manner of poisons and diseases. “Do not fear the warmth brought on by theriac” he wrote, “for in small diluted doses it cannot harm anyone.”

The patient should dress in clean, comfortable clothes, “for they stimulate the sense of touch” and should be surrounded with sheets soaked in a mixture of vinegar and theriac, as well as fresh flowers and sweet-smelling roses “for they uplift the sprits of the sick.” Similarly the home should be clean, airy, and adorned with drawings “that make the heart happy.” The best time to undergo bloodletting depending on the complexion of the patient: those who were dark should have the procedure at sunrise, while those who were pale should do so at midnight, and the blood should be removed from the same side as the buboes. Regardless of when it was performed, the patient should first take a laxative.

And then there is this advice:

Avraham Yagel. Moshia Hosim. Venice 1587. 18a.

And there is the incredible thing mentioned in the first chapter of tractate Kerisut which states “and urine is good for it (the Temple incense).” In addition those who are learned about nature have taught that it is useful and good to take the urine of a young, handsome, and healthy boy, and to drink it each morning. It will filter out the bad air (that causes the plague).

Now some might use this as evidence that the rabbis of the post-talmudic era had no idea about medicine. But that is not the case. What this teaches is quite the opposite; that many were up-to-date with the very latest medical thinking - even if, by our standards, that thinking was quite wrong.

Everyone recommended drinking urine

The German medical historian Karl Sudhoff (1853-1938) made a career studying almost 300 plague texts from the early Middle Ages. He noted that in one Latin treatise on health written in 1405, “older patients who were sometimes counseled to drink a boy’s fresh urine might (understandably enough) feel some nausea.” Yup. And in the excellent recently published book Doctoring the Black Death, John Aberth, who seems to know everything about medieval Europe’s medical response to plague wrote that as an alternative to theriac, that ancient concoction that was supposed to prevent and cure any and all manner of diseases, people drank urine. For example in 1378, Cardo of Milan prescribed a potion “for the poor that combined the patient’s own urine with mustard, castor oil, pomegranate, juniper, sage and reddish, and which was to be boiled, clarified and strained, then taken morning and evening, five spoonfuls at a time. (205)” And an Italian physician named Dionysus Secundus Colle who recovered from the plague around 1348 had this to say (248):

I have seen women gathering snails and capturing lizards and newts, which they asserted that, once they had all been burnt down to a powder…they administered two drachmas of it in a boy’s urine, and they cured and persevered many, and afterward I was compelled to investigate [this sure myself] and afterwards I cured many.

Jewish folk remedies continued to use urine as a medicine. Yudel Rosenberg (1859-1935) mentioned it as a treatment for swelling in his book published in Peitrikow in 1911:

Yudel Rosenberg. Rafael Hamalakh Peitrikow 1911, 70

Swelling: Where there are no pharmacies, a popular physician can dip a rag into the urine from young children, and place it repeatedly on the swelling. This sometimes helps.

So urine was thought to have many helpful properties. It helps the tone of a shofar, improves theTemple incense, and was once thought to be a cure for the plague. Still, we are unlikely to use it in any of these ways any time soon. And, as Abba Shaul noted, that’s probably a good thing.