In today’s page of Talmud there is the story told about a physician named Tuviah.

ראש השנה כב, א

מַעֲשֶׂה בְּטוֹבִיָּה הָרוֹפֵא שֶׁרָאָה אֶת הַחֹדֶשׁ בִּירוּשָׁלַיִם, הוּא וּבְנוֹ וְעַבְדּוֹ מְשׁוּחְרָר, וְקִבְּלוּ הַכֹּהֲנִים אוֹתוֹ וְאֶת בְּנוֹ וּפָסְלוּ אֶת עַבְדּוֹ. וּכְשֶׁבָּאוּ לִפְנֵי בֵּית דִּין — קִבְּלוּ אוֹתוֹ וְאֶת עַבְדּוֹ, וּפָסְלוּ אֶת בְּנוֹ

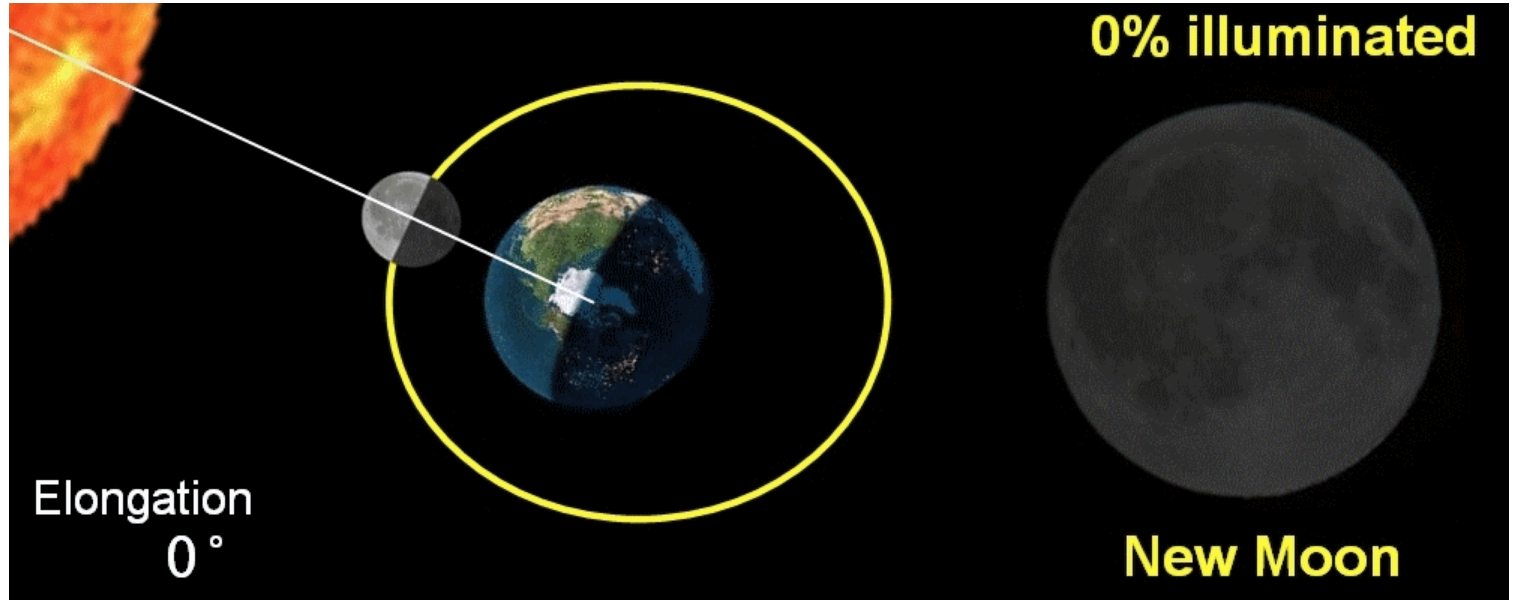

There was an incident with Tuviah the doctor. When he saw the new moon in Jerusalem, he and his son and his freed slave all went to testify. The priests accepted him and his son as witnesses and disqualified his slave, for they ruled stringently that the month may be sanctified only on the basis of the testimony of those of Jewish lineage. And when they came before the court, they accepted him and his slave as witnesses and disqualified his son, due to the familial relationship.

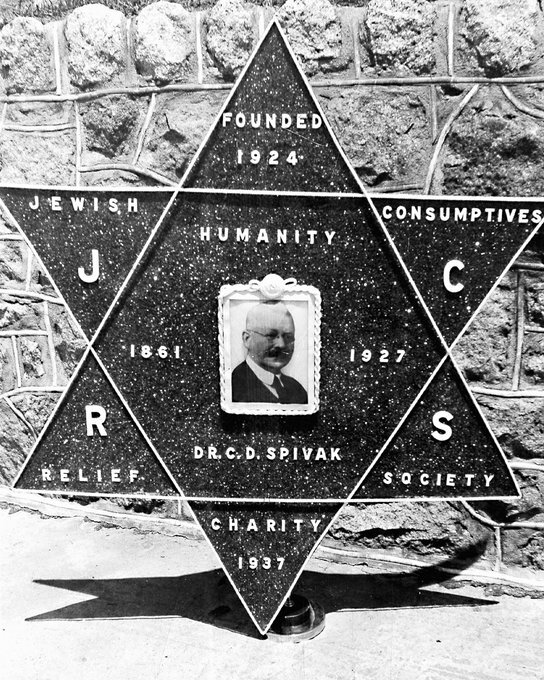

The story is told to demonstrate a disagreement over whether a father and son may jointly testify about having seen the new moon, because ordinarily witnesses must not be related. It also demonstrates another disagreement over whether a slave may give testimony about the new moon. But for our purposes we will not focus on either of these issues. Instead we will discuss a namesake of the Tuviah mentioned in this Mishnah. He was Tuviah Cohen, born in the town of Metz in northeastern France in 1652, and like the Tuviah in the Mishnah he was a physician “who saw the new.”

The Other Tuviah

Portrait of Tuviah Cohen, from his work Ma’aseh Tuviah, Venice, 1708.

This Tuviah Cohen has long been a favorite of historians of science and Judaism. Perhaps this is because he was a reformer of sorts, ready to sweep away old superstitions and replace them with scientific knowledge. Perhaps it is because his book, Ma’aseh Tuviah, was “ ... the best-illustrated Hebrew medical work of the pre-modern era,” full of wonderful drawings about astronomy and anatomy. Perhaps it is because his book is so clearly printed and a pleasure to read in the original. Or perhaps it is because Cohen was so adamantly opposed to Copernicus that he called him the “Son of Satan”—which made his the first Hebrew work to attack Copernicus and his heliocentric system.

In fact, introducing new science was of such importance that it was the motivation behind the name of Cohen’s book, Ma’aseh Tuviah. Cohen reminded his readers of the Mishnah on Today’s page of Talmud: “It happened (ma’aseh) to Tuviah the doctor who saw the new [Moon] . . . and the Bet Din [rabbinic court] accepted his testimony.” Cohen saw himself as another doctor who would “see the new.

After his father’s untimely death, Tuviah’s mother remarried in 1664 when he was twelve years old. He studied in a yeshivah in Cracow, and at the age of twenty-six, entered the University of Frankfurt, where he began to study medicine. Despite being taken under the wing of Fredrick William, the elector of Brandenburg, and receiving a stipend from him, anti-Jewish sentiment prevented Cohen from graduating. As a result, he left for the University of Padua, where he graduated with a degree in medicine in 1683 and soon found employment as a physician in Turkey. He published his only work, Ma’aseh Tuviah (The Work of Tuviah), in Venice in 1708 and moved in 1715 to Jerusalem, where he died in 1729.

Front page of the first edition of Ma’aseh Tuviah, Venice 1707.

Tuviah’s Famous Encyclopedia

Tuviah painfully remembered one particular area in which he lacked knowledge: the discipline of astronomy. It was astronomy that the Talmud considered to be the example par excellence of Jewish wisdom that would be acknowledged by Gentiles. Examining the verse “For this is your wisdom and understanding among the nations” [Deut. 4:6], the Talmud had concluded that it referred to “the calculation of the seasons and the constellations,” that is, the ability to create an accurate calendar and to forecast the positions of the stars and planets. Tuviah was especially troubled by the taunts that Jews had no proper astronomical understanding, given the pride of place of astronomy in the Talmud. He recalled his days in the university:

We would undertake long debates with us every day about questions of belief, and would many times embarrass us asking “where is your wisdom and understanding—it has been taken from you and given to us!” Although we were knowledgeable in Bible, Talmud and Midrashim, we were like paupers when we debated them. This is why I became a zealot for the Lord and swore that before I died I would neither sleep nor rest until I had written a work that included knowledge and skills...for although we walk in this dark and bitter exile God has been our light and there are still wise and learned men among us. . . .

He therefore addressed this topic in detail in his encyclopedic Ma’aseh Tuviah.

The first depiction of the heliocentric system in Hebrew literature. From Ma’aseh Tuviah, Venice, 1708, 50b.

Copernicus is “the Firstborn of Satan”

Tuviah’s section on astronomy included the first depiction in Hebrew literature of the new(wish) heliocentric model of the universe, first published by Nicolas Copernicus in 1542. But having explained the new model (which by then was nearly two centuries old) he rejected it in favor of the traditional earth centered or geocentric model. And he did so with an unforgettable chapter title:

Chapter Four.

Bringing all the claims and proofs used by Copernicus and his supportersshowing that the Sun is at rest and the Earth is mobile;

and know how to refute him, for he is the First born of Satan.

The Rest of Tuviah’s Encyclopedia

Besides astronomy, the Tuviah’s encyclopedia contains dozens of other topics, all of which demonstrate that Tuviah was a product of his time (for how could he be anything other?) Ma’aseh Tuviah (which you can read and download here) contains a section on Hokmat HaPartzuf, which today we might recognize as an amalgam of phrenology, physiognomy and palm-reading. Tuviah defined Hokmat HaPartzuf as “the ability to divine the future, by understanding the form, size and limbs of the body, the way a person looks, his color, size, nature, intelligence, his spirit whether it be large or small, and many other qualities like this.” All of these, wrote Tuviah, were reliable predictors of a person’s future, as was generally accepted in his day. He also described the nature of giants, which were described in the Bible as Nefilim or Refa’im, and noted that giants (anakim) were to be found in a number of different climates. For the sake of brevity, he wrote, he would only describe one event to which he was an eye-witness. In 1694 in Salonika in northern Greece, workers in a salt mine uncovered the remains of a giant “thirty-three amot in length”. Tuviah describes seeing two bones of the forearm and one tooth, “which weighed 350 drachmas”, or about 1.5kg. It was most likely that Tuviah had seen fossilized prehistoric remains, which he attributed to the bones of a giant human.

Tuviah also found no reason to doubt the existence of centaurs, mermaids and sirens, and creatures who were nourished through an umbilical cord that attached them to the earth. The latter, which resembled a sheep and which grew from the Boramets tree, were to be found in Africa and although Tuviah had not personally seen them he relied on new but unnamed works of geography to inform his own readers of the existence of these fantastic creatures.

In the section on medicine, Tuviah, Like all the physicians of his time, he recommended bloodletting, and in another he discussed “The French Disease”, which today we call syphilis. Tuviah described it as being recently introduced from India or the newly discovered America:

In 1496 the great explorer Christopher Columbus returned with his sailors from exploring the new world, but they began to act immorally with the women of Italy which angered God greatly and He brought about a great calamity and a great sickness. And the French army which was then fighting around Naples also became sick, which is why the disease is known today as mal francese, although it is in fact an Indian or an Italian disease. Some Latin books call it lues veneris or pudendagra.[1]But I call it the small plague because it attacks women and men. I call it this for three reasons: First, it is the result of immorality. Second its poison is like that of a plague. It is spread by a man having intercourse with an infected woman, and in an instant it spreads throughout the body. Thirdly, it acts just like a plague but a plague kills, and this is not usually lethal…but rather causes suffering that is worse than death.

There are, Tuviah noted, a number of theories as to the etiology of the French disease. Galen believed it was from rotting blood and the alchemists thought it was caused by an acidic poison. “However” he concludes, “it is sufficient for us to know that it is caused by unclean intercourse [bi’ah teme’ah] that transmits an uncleanliness through contact. This causes God to become angry, for he abhors immorality.”

Tuviah’s famous illustration

Ma’aseh Tuviah was a work that relied on ancient medical teachings that had never been challenged, together with a few more recent sources, but all of Tuviah’s choices reflected the general medical consensus of his time. Perhaps more innovative was Tuviah’s image of the body as a house, an image that is certainly more well-known than is the book in which it appears. On the left of the image is a schematic of the torso of a dissected body, and on the right a four-story house with a roof and chimney. The eyes on the body correspond to the upper windows of the house, and the shoulders correspond to the roof. The liver and gall bladder were drawn as an oven, the heart is oddly identified hidden behind a lattice, and the kidneys correspond to a fountain. The smoking cauldron that appears in the center of the house represents the stomach. The British medical historian Nigel Allan noted that such analogies were not new. William Harvey had also described the stomach as the kitchen, and “the furnaces that draw away the phlegm” but this would not have been known to Tuviah. Even if identifying the workings of the body with the technology of the era was not unique to Tuviah, this image is nonetheless a striking one, and a perennial favorite in discussions of pre-modern Jewish medicine. This image did much to suggest a spirit of innovation in Ma’aseh Tuviah, when in truth the work was far more conservative than innovative.

Tuviah “who saw the new”

Tuviah saw himself as an iconoclast. This was the motivation behind the name of his book, Ma’aseh Tuviah, and it was reflected in the titles he gave to some of the sections in his book: A New Land, or A New House. A careful reading of the text, however, reveals that there was little in Tuviah’s approach to medicine that was new. In fact, much of it contained the ancient classic teachings of Hippocrates, Aristotle, and Galen, and many of the more “recent” plant remedies that Tuviah cited were about one hundred and fifty years old by the time that he published them. Even William Harvey’s discovery of the circulation of the blood could not be considered a novel idea by the time it was mentioned by Tuviah. Harvey has first published his discovery in Frankfurt in 1628, and by 1650 it had been widely discussed throughout Europe and cited in books published in Frankfurt, Venice, Leyden, Rotterdam and London. Rene Descartes cited Harvey’s work in some detail in his Discourse published in 1637. The Pope’s own physician defended the Harverian hypothesis in 1642, and it was discussed by Italian physicians soon after. In 1650 another graduate of the medical school at Padua, Paul Slegel, published a book on the circulation and by 1656 at least thirty-six printed books had mentioned the discovery of the circulation. It is therefore far from surprising that Tuviah also mentioned William Harvey, and doing so makes his early eighteenth century textbook up to date, rather than pioneering.

Ma’aseh Tuviah is a fascinating read, but it is not something you’d like your physician or science teacher to be using as a guide book. Still, his book is an insight to the world of an eighteenth century Jewish physician that is now, thankfully, of historic interest alone.

[Want to read more about Ma’aseh Tuviah? Checkout Chapter Five of this book.]