If an illness is life-threatening, the usual rules concerning Shabbat or Yom Tov (Jewish festivals) may be overridden. On this page of Talmud the rabbis discuss one of these conditions, the deadly disease we call rabies.

יומא פג, ב

ת"ר חמשה דברים נאמרו בכלב שוטה פיו פתוח ורירו נוטף ואזניו סרוחות וזנבו מונח על ירכותיו ומהלך בצידי דרכים וי"א אף נובח ואין קולו נשמע

The Sages taught in a baraita: Five signs were said about a mad dog: Its mouth is always open; and its saliva drips; and its ears are floppy and do not stand up; and its tail rests on its legs; and it walks on the edges of roads. And some say it also barks and its voice is not heard.

Many of these features are certainly found in rabid dogs. They are not able to swallow and therefore drool; cranial nerve abnormalities may be the cause drooping ears. It will appear skittish, and because of the way its larynx is affected because it cannot swallow, it cannot bark properly. Thus “its voice is not heard.”

Rabid dogs in the Talmud

Elsewhere the Talmud allows a person to kill a mad dog on Shabbat, even though this is an act that is normally forbidden. The reason is that these dogs are likely to bite people and transmit deadly rabies.

שבת קכא, ב

חֲמִשָּׁה נֶהֱרָגִין בְּשַׁבָּת, וְאֵלּוּ הֵן: זְבוּב שֶׁבְּאֶרֶץ מִצְרַיִם, וְצִירְעָה שֶׁבְּנִינְוֵה, וְעַקְרָב שֶׁבְּחַדְיָיב, וְנָחָשׁ שֶׁבְּאֶרֶץ יִשְׂרָאֵל,

Five creatures may be killed even on Shabbat, and they are: The poisonous fly that is in the land of Egypt, and the hornet that is in Ninveh, and the scorpion that is in Chadyab, and the snake that is in Israel, and a mad dog in any place.

The Cause of Rabies

ממאי הוי רב אמר נשים כשפניות משחקות בו ושמואל אמר רוח רעה שורה עליו

From where did the dog become mad? Rav said: Witches play with it and practice their magic on it, causing it to become mad. And Shmuel said: An evil spirit rests upon it.

Like all infectious diseases, the cause of rabies remained unknown until the germ theory of disease and much later the discovery of viruses. Hence the reasonable suggestion that it was caused by witchcraft or an evil spirit.

But rabies is not caused by witchcraft. It is caused by a virus from the family Rhabdoviridae called Lyssavirus. It is found on all continents except Antartica. (Australia has only a certain variant of rabies which you can read about here.) Because the virus is very fragile it cannot survive outside of its host, so you cannot get it from the environment. An animal has to bite you.

In his famous work History of Animals, Aristotle thought that rabies could not be transmitted from a rabid dog to a human.

Dogs suffer from three diseases; these are named rabies, dog-strangles, foot-ill. Of these, rabies produces madness, and when rabies develops in all animals that the dog has bitten, except man, it kills them; and this disease kills the dogs too. The strangles too destroys the dogs; and only few survive after the foot-ill. Rabies also attacks camels. But elephants are said to be immune to all ailments, but to be troubled by internal winds.

But Aristotle was wrong. Dogs can certainly transmit rabies to people. In fact, rabid dogs are the most common cause of transmission of rabies worldwide. But other mammals can also transmit this dreadful disease, as you can see below.

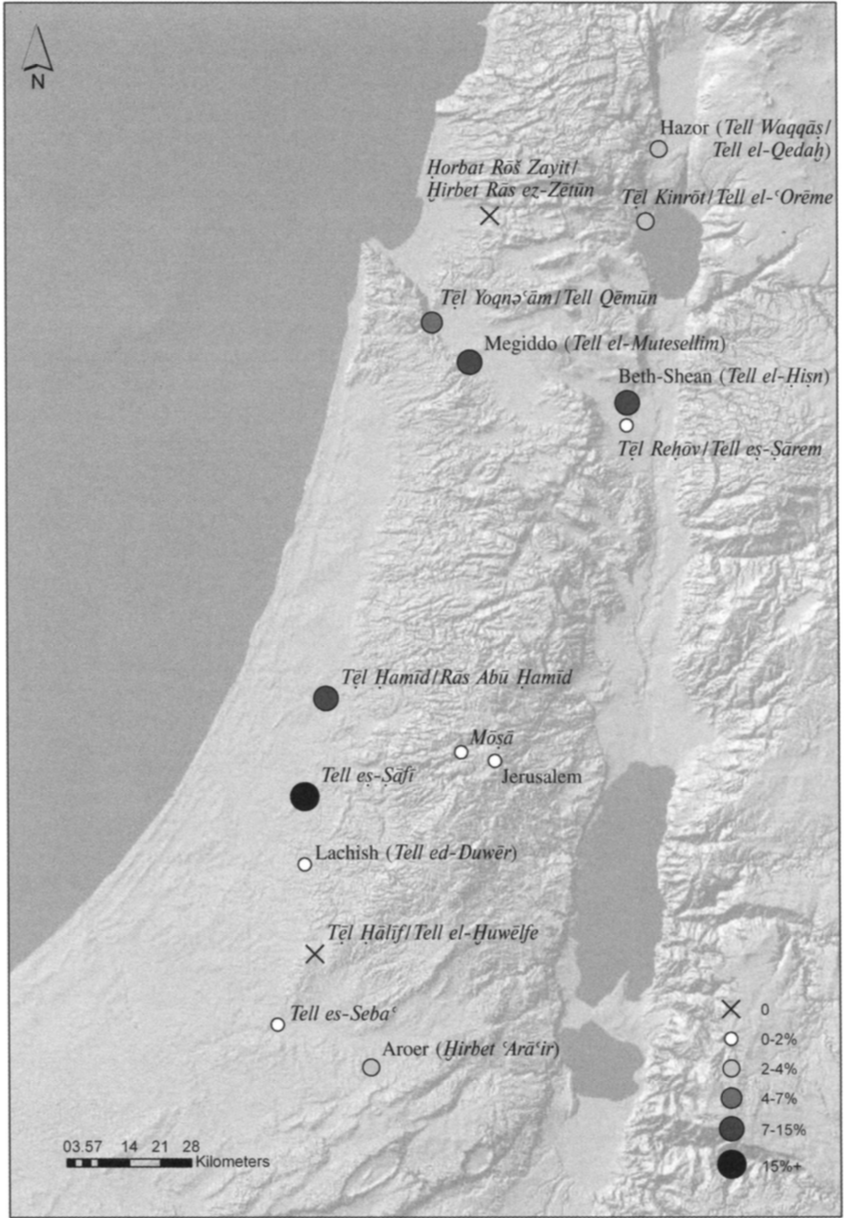

Global distribution of mammalian rabies reservoirs and vectors. From Charles E Rupprecht, Cathleen A Hanlon, and Thiravat Hemachudha. Rabies Re-examined. Lancet Infect Dis 2002; 2: 327–43

A Case of Rabies in the US

An estimated 59,000 people die worldwide each year from rabies. That’s about one person every nine minutes. In the US the disease is virtually unknown; only between one and three people per year get the disease. Here is a case report of a what happened in 2018 when a man caught rabies in Utah, courtesy of Morbidity and Mortality Reports, published by the Centers for Disease Control.

On October 17 and 18, 2018, a man aged 55 years who lived in Utah sought chiropractic treatment in Idaho for neck and arm pain thought to be caused by a recent work-related injury. On October 19, he was evaluated in the emergency department of hospital A for continued neck pain, nuchal muscle spasms, burning sensation in his right arm, and numbness in the palm of his right hand. He had no fever, chills, or other symptoms of infection. Dehydration was a concern because the patient reported he was unable to drink liquids because of severe pain and muscle spasms. The patient received a prescription for a steroid for muscle spasms and decreased sensation in the right arm and was discharged home.

Two days later, on October 20, the patient developed shortness of breath, tachypnea,{rapid breathing] and lightheadedness and reported he had not been able to sleep for 4 days; he was transported by ambulance to hospital B. The patient continued to have right upper extremity pain and severe esophageal spasms, causing him to refuse oral fluids. Because of his worsening symptoms and acute delirium, he was transferred to hospital C.

On October 21, the patient was intubated for airway protection {ie sedated and connected to a breathing machine]. His symptoms worsened, with fever to 104.7°F (40.4°C), and he became comatose on October 25. Additional exposure history collected from family members included ownership of two healthy dogs and a healthy horse, and a recent grouse-hunting trip where the patient had dressed and cleaned the birds while wearing gloves. High-dose corticosteroid treatment was initiated for presumed autoimmune encephalitis. Because of refractory seizures beginning on October 26, he was transferred to hospital D on October 28, where steroids were continued. On November 3, an infectious disease physician was consulted at hospital D who noted that the patient’s symptom of spasms when swallowing suggested a possible diagnosis of rabies. When specifically questioned about the patient’s exposure to wild animals, family members reported extensive contact with bats that had occupied the patient’s home in the weeks before illness onset… The patient continued to decline, supportive care was withdrawn, and he died on November 4, 19 days after symptom onset.

It took four hospitals over two weeks to diagnose the cause as rabies, because the disease is so very rare in the US that doctors naturally don’t consider it. By then there was nothing that could be done to save the patient. At post-mortem specimens were collected, which indicated that the virus identified was that of a rabies virus variant associated with Mexican free-tailed bats (Tadarida brasiliensis).

The treatment of rabies

Here is the Talmudic remedy for rabies.

יומא פד, א

דנכית ליה מיית מאי תקנתיה אמר אביי ניתי משכא דאפא דדיכרא וניכתוב עליה אנא פלניא בר פלניתא אמשכא דאפא דיכרא כתיבנא עלך כנתי כנתי קלירוס ואמרי לה קנדי קנדי קלורוס יה יה ה' צבאות אמן אמן סלה ונשלחינהו למאניה ולקברינהו בי קברי עד תריסר ירחי שתא ונפקינהו ונקלינהו בתנורא ונבדרינהו לקטמיה אפרשת דרכים והנך תריסר ירחי שתא כי שתי מיא לא לישתי אלא בגובתא דנחשא דילמא חזי בבואה דשידא וליסתכן כי הא דאבא בר מרתא הוא אבא בר מניומי עבדא ליה אימיה גובתא דדהבא

One bitten by a mad dog will die. The Gemara asks: What is the remedy? Abaye said: Let him bring the skin of a male hyena and write on it: I, so-and-so, son of so-and-so, am writing this spell about you upon the skin of a male hyena: Kanti kanti kelirus. And some say he should write: Kandi kandi keloros. He then writes names of God, Yah, Yah, Lord of Hosts, amen amen Selah. And let him take off his clothes and bury them in a cemetery for twelve months of the year, after which he should take them out, and burn them in an oven, and scatter the ashes at a crossroads. And during those twelve months of the year, when his clothes are buried, when he drinks water, let him drink only from a copper tube and not from a spring, lest he see the image of the demon in the water and be endangered, like the case of Abba bar Marta, who is also called Abba bar Manyumi, whose mother made him a gold tube for this purpose.

Well, the first sentence is certainly correct: “One bitten by a mad dog will die.” In fact the Jerusalem Talmud (Berachot 8:5) states that you will never hear of a case in which a person was bitten by a mad dog and actually survived, presumably despite the use of male hyena skin.

However, today there is a remedy for a person who was bitten, so long as you get to it quickly. You can give the person rabies immunoglobulin which contains the antibodies to fight the virus. But you have to give it right away, and the patient needs a total of five shots over a month. Once the patient develops symptoms, as the man from Utah did, this intervention does not work, and the disease is uniformly fatal. In all of medical literature there is but a single case report from 2005 of a person who survived after developing the symptoms of rabies. The patient was a 15 year old girl who had been bitten by a bat that she was trying to remove from her room. The doctors thought that her chances of survival were negligible, and offered hospice care as one option and aggressive therapy with antivirals as another. They told the girl’s parents about “the probable failure of antiviral therapy and the unknown effect of the proposed therapy, as well as the possibility of severe disability if the patient were to survive.” Faced with this awful choice the parents requested aggressive care. The girl was in a coma for almost a month, but survived, although she was left with residual neurological problems.

“Survival of this single patient does not change the overwhelming statistics on rabies, which has the highest case fatality ratio of any infectious disease. Any regimen may be ineffective in cases associated with extremes of age, massive traumatic inoculation, or delayed diagnosis and must be coupled with strategies to reduce the risk of complications from long-term treatment in the intensive care unit.”

The Mishnah in Yoma (8:6) suggests a controversial remedy for a person bitten by a rabid dog.

מִי שֶׁנְּשָׁכוֹ כֶלֶב שׁוֹטֶה, אֵין מַאֲכִילִין אוֹתוֹ מֵחֲצַר כָּבֵד שֶׁלוֹ, וְרַבִּי מַתְיָא בֶן חָרָשׁ מַתִּיר

If one was bit by a mad dog, they do not feed him the lobe of its liver. But Rabbi Matia ben Harash permits it.

Before you email me with the idea that perhaps this would give the patient some antibodies, you should know that it would not. First, you are likely to get a mouthful of the rabies virus which may increase your exposure dose if you had any open sores or cuts allowing it to enter the bloodstream. Second, a rabid dog won’t have made some or perhaps any antibodies. That’s why it is rabid. And third, You need to get antibodies into the bloodstream. They will be broken down in the harsh environment of the stomach, rendering them useless.

In fact the Talmud Yerushalmi (Yoma 8:5) records that the German servant of Rabbi Yudin was bitten by a mad dog and was given the its liver to eat. But he died, leaving the Talmud to conclude for a second time that you will never hear of a case in which a person survived a dog bite from a rabid dog.

ירושלמי יומא 8:5

גרמני עבדיה דר' יודן נשייא נשכו כלב שוטה והאכילו מחצר כבד שלו ולא נתרפא מימיו אל יאמר לך אדם שנשכו כלב שוטה וחיה

In his commentary on the Mishnah, Maimonides, who was of course a physician himself, ruled that we do not accept the position of Rabbi Matia:

רמב׳ם פירוש המשניות יומא 8:6

ואין הלכה כרבי מתיא בן חרש בזה שהוא מתיר להאכיל לאדם הכבד של כלב שוטה כשנשך כי זה אינו מועיל אלא בדרך סגולה. וחכמים סוברים כי אין עוברין על המצות אלא ברפואה בלבד ר"ל בדברים המרפאין בטבע והוא דבר אמתי הוציאו הדעת והנסיון הקרוב לאמת. אבל להתרפאות בדברים שהם מרפאים בסגולתן אסור כי כוחם חלוש אינו מצד הדעת ונסיונו רחוק והיא טענה חלושה מן הטועה

We do not follow the opinion of Rabbi Matia ben Harash, who permitted feeding the liver of a rabid dog to a person who was bitten, because it does not help, and is only a protective charm (segula). The rabbis only permitted the commandments to be ignored when using real medicines, that is to say, things that have been tested and work, and shown to work with certainty through testing. But it is forbidden to use any kind of charm because they don’t have any power [lit. their power is weak] and experience is limited and this is a mistaken approach…

Although the rabbis of the Talmud suggested remedies for a bite from a mad (rabid) dog, none would work. And today, if you are bitten and show symptoms of rabies, we are basically in the same position, with no medical interventions that work. How humbling.

[Repost from Shabbat 121.]