In a discussion about the permanence of wounds and their ability to heal comes this:

בעא מיניה לוי מרבי מנין לחבורה שאינה חוזרת דכתיב היהפוך כושי עורו ונמר חברברתיו מאי חברברתיו אילימא דקאי ריקמי ריקמי האי ונמר חברברתיו נמר גווניו מבעי ליה אלא ככושי מה עורו דכושי אינה חוזרת אף חבורה אינה חוזרת

Levi raised a dilemma before Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi: From where is it derived that a wound is defined as something irreversible? He answered him that it is derived as it is written: “Can a Cushite change his skin, or a leopard its spots [chavarburotav]?” (Jeremiah 13:23). The Gemara explains: What does chavarburotav mean? If you say that they are spotted marks on the leopard’s skin, that phrase: Or a leopard its spots, should have been: Or a leopard its colors. Rather, chavarburotav means wounds, and they are similar to the skin of a Cushite: Just like the skin of a Cushite will not change its color to white, so too a wound is something that does not reverse.

“Can a leopard change its spots?” It is a famous question from the Book of Jeremiah, asked rhetorically. The presumptive answer is “why no, a leopard cannot change its spots!” And with this in mind, God tells Jeremiah that because the Jewish people don’t change their wicked ways, He will punish them. And so in the next verse God announces that he will scatter the Jewish people “like straw that flies before the desert wind.”

The leopard and its spots is a great analogy, but it turns out to be rather more complicated than perhaps the great prophet first understood.

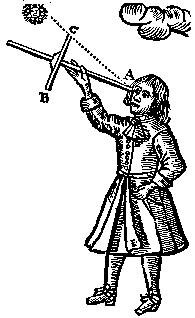

the origins of camouflage in Big Cats

In 2010 William Allen and colleagues published a review of the camouflage patterns in thirty-five different species of wild cats, including lions, panthers, and our leopards. After controlling for the effects of shared ancestry, they found that “the likelihood of patterning and pattern attributes, such as complexity and irregularity, were related to felids’ habitats, arboreality and nocturnality.” In other words, the markings on a wild cat are related to where it lives, how it hunts, and when it sleeps. Because the primary hunting strategy of all cats is to stalk prey until they are close enough to capture them with a pounce or quick rush, the hunts are more successful when an attack is initiated from shorter distances. So the cat must remain undetected for as long as possible and its camouflage helps achieve this. Allen concluded that evolution has generally paired plain cats with relatively uniformly colored, textured and illuminated environments, and patterned cats with environments that Rudyard Kipling described as “full of trees and bushes and stripy, speckly, patchy-blatchy shadows.”

Cats such as leopards – which live in dense habitats, among trees and are active at low light levels – are the most likely to be patterned, especially with irregular or complex shapes. Species that live in open grassland, such as lions, tend to have plainer coats. Allen’s research also explains why black leopards are common but black cheetahs unknown. Unlike cheetahs, leopards live in a wide range of habitats and have varied behavioural patterns.

Leopards without any spots

In fact there are completely black leopards, which are more commonly called black panthers. (One was even kept in the Tower of London in the late eighteenth century.) This feature is called melanism, and according to a 2017 international survey of leopards, it occurs in about 11% of the species. That’s a lot of leopards without any spots.

A leopard that changed its spots. It happens in about 11% of the species. Don’t tell Jeremiah.

But Can People Change?

Despite the rather technical talmudic re-reading of Jeremiah’s verse, there is no doubt as to its original meaning. It was divine despair, as God gave up, as it were, on the ability of the Jewish people to ever meaningfully change its national character. Here, for example is the commentary of the Malbim, Rabbi Meir Leibush Wisser (1809-1879):

,הלא א"א שהנמר יהפך חברברותיו, שצבע עורו הוא טבע כולל בכל המין וכל הנמרים, כן אי אפשר שתוכלו להיטיבאתם למודי הרע שכבר נעשה הרע טבעי לך, ולכן ואפיצם כקש עובר

It is not possible for a leopard to change its spots, (for the color of its skin is its natural state in all of the leopard species,) so it is not possible to incline your natural inclination for the good, for evil has become natural to you. That is why I will scatter you as straw in the wind…

Can we change our characters to a meaningful degree? That is the question we ask each year on Yom Kippur, and the answer we are always given by our spiritual leaders is this: we can change, if we put in the effort that is required. Maimonides also believed that it is possible to change (Laws of Repentence 2:2):

וּמַה הִיא הַתְּשׁוּבָה. הוּא שֶׁיַּעֲזֹב הַחוֹטֵא חֶטְאוֹ וִיסִירוֹ מִמַּחֲשַׁבְתּוֹ וְיִגְמֹר בְּלִבּוֹ שֶׁלֹּא יַעֲשֵׂהוּ עוֹד

What is repentance? The sinner shall cease sinning, and remove sin from his thoughts, and wholeheartedly conclude not to revert back to it…

But are there limits to this belief in the religious ability to repent? Here is perhaps one of the most challenging questions ever seen asked in this context. What happens when a Nazi repents of his beliefs and actions, and asks to convert to Judaism? Must he be accepted, or are there limits, even when we believe that true repentance is possible? This question is found in a 1991 work about the laws of conversion, Chukkat Hager, by Rabbi Moshe Steinberg (1909-1993) who was the Chief Rabbi of the town of Kiryat Yam in Israel:

Regarding a gentile who was once a member of the Nazi Party, and it is likely that he himself took part in war crimes, and who now has repented and wishes to become Jewish, should we accept him?

What do you think? Assuming the former Nazi was indeed repentant, would you approve of his conversion to Judaism? If not, why not? Is it because a leopard cannot change its spots?

[If you want to read how Rabbi Steinberg ruled on the question, click here, but first formulate your own opinion…]