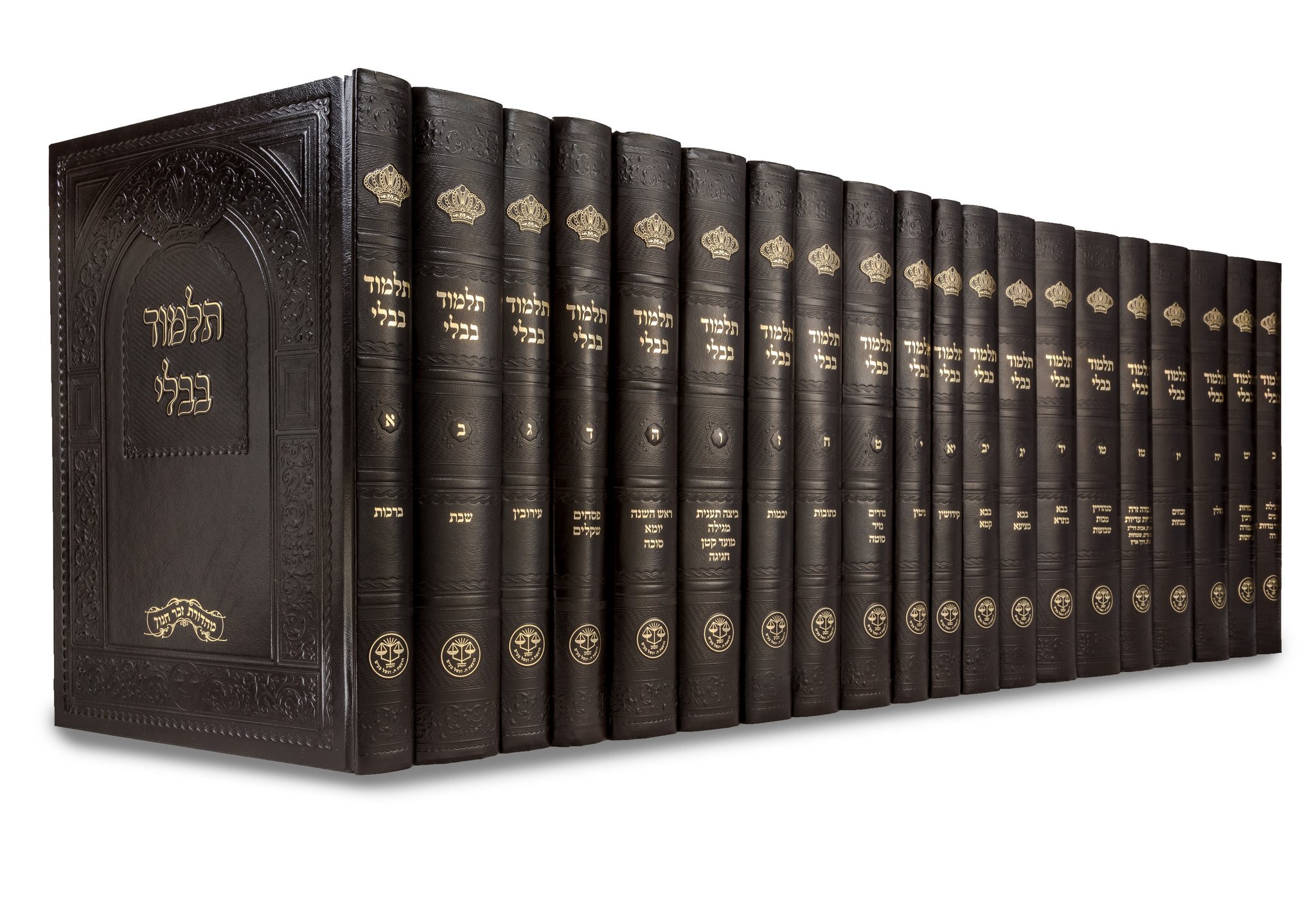

As astute readers who have followed Talmudology since its inception will have already noted, last week we reached an incredible milestone. The last post, on Yevamot 42, was not just another day in the life of Talmudology. Because, seven and a half years ago, on November 15, 2014, an earlier version of that post was the very first one published on Talmudology. That’s right. It means that we have now completed Talmudology on the entire Babylonian Talmud.

Over the last seven and a half years Talmudology has published about 320 original essays, several of which were re-posted when the Talmud repeated itself. Over those years, this website has had over 221,000 unique visitors, and over 390,000 page views. That’s a lot of Talmudology.

What’s Next for Talmduology?

We will continue to re-publish our posts following the one-page-a-day Daf Yomi cycle. If you teach Daf Yomi, you can navigate to our Topics by Tractate section, and see what is available for each page before it comes up.

In addition, we will put out new material whenever the occasion calls for it. For example we never addressed the topic of weird and outlandish cases in the Talmud, so that will be remedied with a brand-new post on Yevamot 54. In addition to adding material we managed to skip the first time, the existing posts will be updated whenever necessary, because while the Talmud doesn’t change, science sometimes does.

We also hope to publish Talmudology in a two (to perhaps three) volume work, making it accessible on Shabbat, and available as a gift for your favorite Bar or Bat Mitzvah. This is an exciting (if daunting) project, and we are in discussion with a major publisher, so stay tuned…

Over the last seven and a half years, a lot has happened. I danced at the weddings of three of my children, and celebrated the birth of four grandchildren. I travelled widely, mourned the loss of a parent, underwent heart surgery, and watched with great pride as my wife took on a new position at Yeshiva University. In other words, life. Throughout it all I had Talmudology to keep me out of mischief; it was, and still is, a joy to produce.

Thank you to the many readers who pointed out errors of fact or grammar, and who made suggestions to improve the posts and sent fascinating material to help me do so. You have made Talmudology better, and your letters of support have brought many a smile to my face.

חזק ונתחזק

Jeremy