On today’s page of Talmud the rabbis continue their discussion of the circumstances under which the normal rules of Yom Kippur may be abrogated. What happens if a building collapses and there are victims buried in the rubble (a scenario we recognize only too well)? A search for the victims may be carried out but with some caveats, one of which is the topic of today’s post.

יומא פה, א

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: עַד הֵיכָן הוּא בּוֹדֵק? עַד חוֹטְמוֹ. וְיֵשׁ אוֹמְרִים: עַד לִבּוֹ

The Rabbis taught: If a person is buried under a collapsed building, until what point does one check to clarify whether the victim is still alive? [Until what point is he allowed to continue clearing the debris?] They said: One clears until the victim’s nose. If there is no sign of life, [i.e., if he is not breathing,] he is certainly dead. And some say: One clears until the victim’s heart [to check for a heartbeat]…

These few lines are the basis of an extremely important area of Jewish law, for they are fundamental to the question of when, exactly, a person may be declared dead. This has implications not only for the burial and the process of mourning to begin, but also for any decision to be made regarding the post-mortem donation of life-saving organs. In this post we will get into the details of how Jewish law is determined by today’s page of Talmud. But to do so we first need to detour into the history of the definitions of death. Ready? Let’s go.

“At the moment we have to define death as cessation of the heartbeat ... there may come a new definition—but that would have to be accepted by lawyers, medical examiners as well as the lay public....””

Part 1. A Brief History of Brain Death

Before the era of mechanical respirators that take over the work of breathing, the process of breathing and the heartbeat were inextricably linked. If a person could not breath for a few minutes, (perhaps because they had drowned) the heart would soon stop beating. This would end the flow of blood to the brain which would quickly cease to function. Since the brain stem controls breathing, the person would longer take any breaths. There could be no return to life, no more beating of the heart. The person was dead. No breathing and no heartbeat.

The problem began when we could start a stopped heart with electrical defibrillation, and provide oxygen to a body that would not breathe on its own by using a mechanical ventialator.

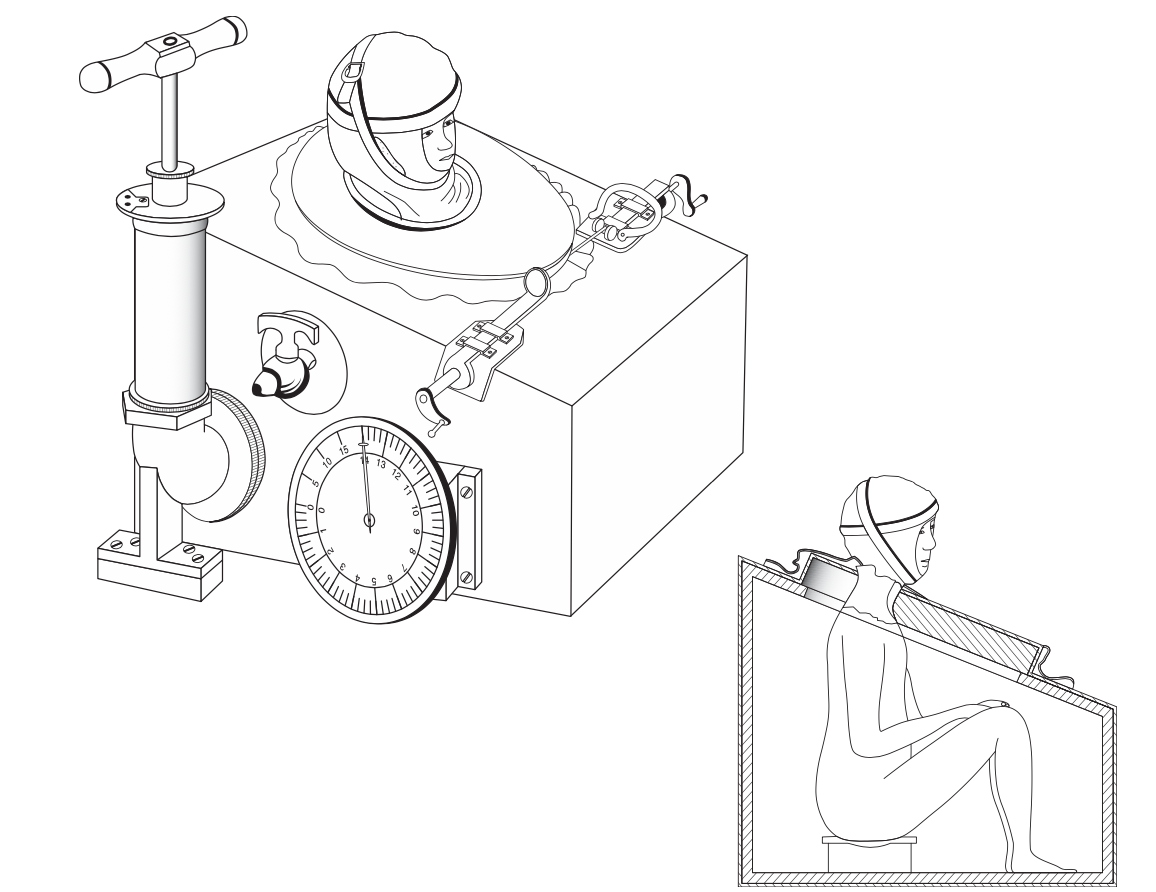

Body-enclosing box. One of the first known body-enclosing boxes; patented by Alfred Jones in 1864.

Mechanical ventilation has been around in some form or another since the late 19th century, when in 1867 Alfred Woillez built the first workable iron lung, which he called the “spirophore.” He proposed to place them along the River Seine to help drowning victims, but the machine was difficult to use since it prevented access to the patient. It was the polio pandemic of the 1950s that prompted the development of improved mechanical respirators, as many of the patients developed a transient but deadly paralysis of the muscles of respiration. If the work of breathing could be outsourced to a machine, these patients might be saved. As machines were perfected to do just that, the mortality rate of these polio victims dropped from 87% to 40%. But that was just the beginning. “Over the past 60 years,” wrote Arthur Slutsky in his 2015 paper on the history of mechanical ventilation “many technical aspects of ventilators have dramatically improved with respect to flow delivery, exhalation valves, use of microprocessors, improved triggering, better flow delivery, and the development of new modes of ventilation.”

Now the sequence of events we outlined a moment ago became upended. Remember, if a person could not breath for a few minutes the heart would soon stop beating. This would end the flow of blood to the brain which would quickly cease to function. Since the brain stem controls breathing, the person would longer take any breaths. But if the work of breathing could be artificially sustained before the heart stopped, there could indeed be a return to something resembling life, and the heart might continue to beat. Often however, the period of anoxia during which no oxygen flowed to the brain (usually no more than 5-10 minutes at most) would result in the brain as an organ dying. We now had a body with a spontaneously beating heart attached to a respirator that performed the work of breathing, but a brain that was dead. What then, is the status of the person? She looks like she is sleeping. Her heart is beating and the machine that is breathing for her is providing oxygen to the lungs from where it is distributed to the rest of the body. All of her organs bar one are working: her kidneys make urine, her pancreas makes insulin and her liver continues to scrub her blood. But her brain is dead. Is she technically, legally, ethically or meaningfully alive, or not?

In his excellent review of the history of brain death as death, the neurologist Michael A. De Georgia notes that the modern era of debate began in 1947 when, for the first time, a defibrillator was used to shock a heart back into life. “Suddenly, death was “reversible.”” Then the first mass- produced ventilator, the Bird Mark 7, was introduced in 1955, and now the work of breathing could be done by a machine, even if the brain that would ordinarily control breathing was itself dead. It was then that the transition from a heart focused to a brain focused definition of death began to take hold.

Around the same time the field of organ transplantation was also beginning. In 1954, Joseph Murray from the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital, reported the first successful kidney transplant from one identical twin into another, and this was soon followed by the first liver transplant and the first lung transplant. But the donors were cadavers, the transplants soon failed and the recipients quickly died. Then everything changed when Christiaan Barnard carried out the world’s first successful human heart transplant in South Africa on December 3, 1967.

The Harvard Ad Hoc Committee

Meanwhile there was uneasiness around the care of what was called at the time the “hopelessly unconscious patient.” In January 1968 the Dean of the Harvard Medical School Robert Ebert formed an Ad Hoc Committee to formulate the new definition of death. The committee consisted of neurologists, a neurosurgeon and a nephrologist together with an attorney, a neuroscientist, a physiologist, a professor of public health, a historian, and an ethicist. It was difficult to find consensus because no-one was really sure how to tell if the brain was, well, dead. “Irreversible coma” was prognostic of death but not really equal to death, and anyway what was meant by irreversible, and how would that be measured? The Ad Hoc Committee came up with some suggestions.

First there was “unreceptivity and unresponsivity” which is the central feature of irreversible coma. Then there were “no movements or breathing” as the second criterion. Absent reflexes was the third. Finally, isoelectric (or flat line) EEG was the fourth criterion. The EEG measures electrical activity across the brain. A flat EEG means there is no such activity, and that the brain is dead. When patients met all the criteria, they would be considered essentially dead.

As Degorgia noted, the Harvard report did not really provide a fully worked out and conceptually coherent notion of what brain death was. Instead they said this: “Any organ, brain or other, that no longer functions and has the no possibility of functioning is for all practical purposes dead.” Some of the push was coming from transplant surgeons, who were horrified that organs from (brain) dead people were being wasted: “Can society afford to lose organs that are now being buried?... Patients are stacked up in every hospital in Boston and all over the world waiting for suitable donor kidneys. At the same time patients are being brought in dead to emergency wards and potentially useful kidneys are being discarded.” But to be clear, the concept of brain death was not created to benefit transplantation.

Parallel developments that converged in the formulation of the concept of brain death. From De Georgia M. A. History of brain death as death: 1968 to the present. Journal of Critical Care. 2014 29; 673–678.

Normal EEG, measuring electrical activity in the brain. Each line is coming from a different electrode placed on the scalp.

EEG in a brain dead person. The patient was a 23-year-old woman who had a massive intracerebral hemorrhage. She was unresponsive to noxious and other stimuli and had absent brainstem reflexes, fixed dilated pupils, and apnea. Three hours after this recording, respiratory support was discontinued and she was pronounced dead. The little blips on the otherwise flat tracings are artifact from the heartbeat, which is shown in the bottom lead. From here.

Ever Since the Ad Hoc Commission

Since the 1968 publication of the findings of the Ad Hoc Commission, lots has happened. The World Medical Association weighed in. A 1976 Conference of the Medical Royal Colleges and their faculties in the United Kingdom also adopted brainstem death. In 1977 the National Institutes of Health attempted to validate the most commonly used criteria in the United States: coma, apnea, and a flat EEG in a multicenter study. In 1979, the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research was organized to bring clarity to brain death and other ethical issues that had emerged in the 1950s but were crystallized in the case of Karen Ann Quinlan, a young woman in a persistent vegetative state, which it cannot be emphasized enough is not the same as brain death. Not even close. In 1994, the American Academy of Neurology undertook the mission to finally standardize the neurological criteria and Practice Parameters were published the following year. The 3 cardinal findings in brain death were “coma or unresponsiveness, absence of brainstem reflexes, and apnea.” In 2010, they were updated again.

But throughout the 1990s, concerns and criticisms about the report from the President’s Commission persisted. The Commission’s main argument was that whole brain death equaled death because, afterwards, the body ceased to be an “integrated organism” and rapidly became a disintegrating collection of organs. However, by then it was clear that brain-dead patients did not necessarily “dis-integrate” as promised. And then there was the problem of language. Here is De Gerogia:

Brain death has always been problematic. This was recognized from the beginning. “Death is what we are talking about,” Joseph Murray argued, “and adding the adjective ‘brain’ implies some restriction on the term as if it were an incomplete type of death.” The term also implies death of “the brain,” that is, death of the cells and tissues constituting the brain rather than death of the human being. Some argued that even the single word death was inadequate.

When in doubt, establish a commission. So in 2007 another President’s Council on Bioethics was created to address some of these lingering concerns. Their white paper was appropriately called “Controversies in the Determination of Death.” It discarded the ambiguous term brain death, and replaced it with the philosophically neutral term total brain failure. It challenged the various conceptual arguments for brain death advanced over the years and suggested a novel argument that equated death with the “cessation of the fundamental vital work of a living organism—the work of self-preservation.” Total brain failure equals death because the “organism can no longer engage in the essential work that defines living things.”

And that’s basically where we are today. The concept of death evolved as a result of several parallel developments, transitioning from the traditional no breathing and no heartbeat (the cardiopulmonary definition) to a brain-based definition of death. And with that, we can pivot to how Judaism has dealt with all this.

Part 2. The Jewish Views on Brain Death

Although as we have seen, the Talmud itself deals with the question, it is most interesting to note that the modem debate on the definition of death began some two hundred years ago, when the issue became a divisive one within the Jewish community.

Moses Mendelssohn and The Fear of Being Buried Alive

In April 1772 the Duke of Mecklenburg in what is now Germany ordered that burials be postponed for three days in order to prevent burying those who were still alive. 'The edict encouraged the Jews of the duchy to seek the advice of the Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn argued for the continued right of the Jewish community to exercise religious autonomy, and pointed out the prohibition against delaying burial. However, to lessen the possibility of burial alive, Mendelssohn suggested that the Jews obtain a medical certificate prior to burial. His pleas to the Duke were so successful that new regulations along the lines suggested by Mendelssohn replaced the original edict. However, in a letter to the leaders of the Jewish community, Mendelssohn expressed anger at what he considered an unwarranted reaction to the edict, and advised them to agree to it on the grounds that it was not in violation of any Torah principle, and was even to be recommended on medical grounds. Mendelssohn's position was later published anonymously in a local Jewish paper. Mendelssohn's position was criticized by his contemporary, the rabbi and scholar Ya'acov Emden, who the Jewish community had also approached for help. Despite this, many members of the Jewish community began to accept the edict, and refused to bury the dead on the day of their death.

The Chatam Sofer on Death

Some 60 years after the Duke's edict, Rabbi Moses Sofer, known as the Chatam Sofer, wrote "it seems to me, that in the countries under the Czar, many [Jews] delay burial out of respect for the head of state, and through this [the truth of] the matter has been forgotten to such an extent that people believe they arc following a Torah law." It is worth noting just how widespread had become the Jewish practice of following this state law. The Chatam Sofer went on to analyze the definition of death in Jewish law, rejected the work of Mendelssohn, and recommended that burial be dependent on the normal clinical criteria of the establishment of death, rather than on the Duke's criteria, which had ultimately depended on post-mortem changes as proof that death had indeed occurred.

At the time of the Chatam Sofer there was a real doubt over the expertise of the medical profession in determining that death had occurred, and yet the Chatam Sofer insisted that if the halakhic criteria had been fulfilled there was no need to worry about the rare instances when in fact the patient was shown to have been mistakenly certified as dead.

Clearly, Jewish Jaw and custom was affected by the wider medical practices of the day. We can now turn to the primary sources that deal with the Jewish definition of death, which are found on today’s page of Talmud.

In today’s daf we have the earliest and in many ways the most important of all the texts is the discussion of the criterion for determining death. The Talmud describes a terrible situation in which a collapsed building has buried victims. The situation is complicated by the fact that it is Shabbat; clearly normal Shabbat regulations are suspended for the sake of preserving human life. However, once it becomes clear that the individual is dead, no futher rescue work is allowed as normal Shabbat regulations once again take force. The question then hinges on how much of the buried body must be uncovered in order to discover if death has occurred.

…תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: עַד הֵיכָן הוּא בּוֹדֵק? עַד חוֹטְמוֹ. וְיֵשׁ אוֹמְרִים: עַד לִבּו… אַבָּא שָׁאוּל מוֹדֵי דְּעִיקַּר חַיּוּתָא בְּאַפֵּיהּ הוּא, דִּכְתִיב: ״כל אֲשֶׁר נִשְׁמַת רוּחַ חַיִּים בְּאַפָּיו״

How far must one search fin order to ascertain if the victim is dead or alive? Until [one uncovers] his nose. Some say up to his heart ... Abba Shaul agrees that life manifests itself primarily through the nose, as it is written "In whose nostrils was the breath of the spirit of life”

So far it would seem that the dispute in the Talmud is simply one between the view that death is equated with the termination of respiration - the first opinion - and the belief that death is indicated by a failure to detect any heartbeat However, Rav Pappa, the Talmudic sage of the fourth century, explains the exact circumstances of the dispute, and his explanation changes the understanding of definition of death in Jewish law:

אָמַר רַב פָּפָּא: מַחְלוֹקֶת מִמַּטָּה לְמַעְלָה, אֲבָל מִמַּעְלָה לְמַטָּה, כֵּיוָן דִּבְדַק לֵיהּ עַד חוֹטְמוֹ — שׁוּב אֵינוֹ צָרִיךְ, דִּכְתִיב: ״כֹּל אֲשֶׁר נִשְׁמַת רוּחַ חַיִּים בְּאַפָּיו״.

Rav Pappa said: The dispute with regard to how far to check for signs of life applies when the digger begins removing the rubble from below, [starting with the feet, to above.] In such a case it is insufficient to check until his heart; rather, one must continue removing rubble until he is able to check his nose for breath. But if one cleared the rubble from above to below, once he checked as far as the victim’s nose he is not required to check further, as it is written: “All in whose nostrils was the breath of the spirit of life” (Genesis 7:22).

Thus if the face is uncovered first and there is no evidence of respiration, all agree conclusively that death has occurred. The respiratory criterion is accepted by Maimonides and by the Shulchan Arukh; neither requires examination of the heart, and it would seem that they provide an early source for supporting the brain death criterion as acceptable today. After all, there is no dispute that the heart of a brain dead victim is beating. The problem arises when one tries to qualify the significance of this cardiac activity.

Contemporary Interpretations

Among the contemporary Jewish scholars who have declared brain death to be indicative of death as determined in Jewish law are Rabbi Moses Tendler, Professor of Biology and Professor of Talmud at Yeshiva University in New York and Dr Fred Rosner, Professor of Medicine at Mount Sinai School of Medicine, Director of the Department of Medicine at Queens Hospital Center, and the author of a number of books on Jewish Medical Ethics. In a joint paper, Tendler and Rosner argued that “ ... the complete and permanent absence of any brain related vital bodily function is recognized as death in Jewish law” The beating of the heart is not a significant factor in Jewish law (halakha). Moreover, they claim that the fact that parts of the body may continue to move or twitch after death has long been recognized in Jewish sources as being of no consequence in showing that life is still present. The Mishnah rules that there are cases in which an animal may impart ritual impurity whilst it still shows movements after decapitation, even though an animal may only ritually defile after it is definitely dead. The Mishnah gives as an example the tail of a lizard, which once detached from the animal still moves. The tail is no longer alive, and hence the conclusion must be that movement of a limb - and this must include the beating heart - is not itself evidence of life. Rosner and Tendler also claim support from the Shulchan Arukh which has a chapter entitled מי הוא החשוב כמת אף על פי שעודנו חי - "He who is considered dead even though he is yet alive.” This title is itself good evidence that there is indeed a category of person who is legally dead, even though the body shows signs of life. Among those listed are an individual who has broken his neck, or a body “torn on the back like a fish.” The halakha considers these individuals to be legally dead even though they may make spasmodic movements, or indeed have a beating heart. The fact that the connection of the brain to the body has been severed is the reason that they are halakhically dead. Tendler summed up his position like this:

Complete destruction or the brain, which includes loss of all integrative, regulatory, and other functions of the brain, can be considered physiological decapitation, and thus a determinant per se of death of the person.

Dr. Abraham Steinberg, writing in the Hebrew journal of medical halakha Assia also supported the position that brain death is an accepted criterion for death in Jewish law. He emphasized that cessation of respiration is the only accepted sign of death to be found in the early medieval sources and the classic codes of Jewish law. The seventeenth century scholar Rabbi Zevi Ashkenazi is the only halakhic source to suggest cessation of the heartbeat as the sign of death. He based his opinion on the belief that "respiration is from he heart and for its benefit. According to Ashkenazi, cessation or respiration is a sign of death because it indicates that the heart has ceased to function. However, Steinberg points out that this opinion is clearly based on a mistaken understanding of respiratory and cardiac function, and as such carries little halakhic weight. Similarly mistaken according to Steinberg, is the opinion of Rabbi Eliezer Waldenberg (1915-2006) who, in opposing brain death criteria, wrote that " ... examining the nostrils does not indicate that the brain has ceased to function, but rather that there is no longer cardiac activity.” But this is factually incorrect; lack of respiratory function (in the presence of the other necessary criteria) indicates that brain death has occurred and the heart may indeed continue to beat for several days afterwards, if the work of breathing is taken over by a mechanical respirator.

Not all authorities accept that brain death is compatible with Jewish law. Indeed the brain death debate is an example of rabbinic authorities holding completely opposing opinions, based on the same texts and sources. Rabbi David Bleich, the noted American writer on Jewish medical ethics, has voiced strong opposition to those who accept brain death as halakhically valid. In 1989 he wrote that an analysis of the sources "indicate clearly that death occurs only upon cessation of both cardiac and respiratory functions." Rabbi Bleich opined that even according to the view accepted by Maimonides and the Shulchan Arukh that respiratory function is the determining factor in establishing death, absence of cardiac activity is a relevant factor. This position is based on an analysis of the commentary of Rashi, the twelfth century French scholar and renowned expositor of the Bible and Talmud. In explaining the reason for the need to check for respiratory efforts at the nostrils in the Talmudic text in today’s daf quoted earlier, Rashi wrote " ...sometimes life is not recognizable in the heart but it is evident at the nose." For Bleich, the words of Rashi would indicate that " …hypothetically if confronted by a situation in which "life" is not evident in the nose ... but is evident at the heart, cardiac activity would itself be sufficient to negate any other presumptive symptom of death." In another paper Bleich explained that Rashi emphasizes the need to check the nostrils “…because inability to detect a heartbeat is inconclusive ... particularly in the case of a debilitated accident victim who may also be obese and [when] the examination is performed without the aid of a stethoscope." Further support for this position is Rashi's comment that the entire controversy in the Talmud is limited to the case in which the victim is "comparable to a corpse in that he does not move his limbs." Hence according to Bleich's interpretation of Rashi, “... the presence of any vital force (including a heartbeat] .. is, by definition, a conclusive indication that death has not occurred." This view is supported by Rabbi Zevi Ashkenazi, who noted that a weak heartbeat may not be perceptible, and yet the victim may still be alive. R. Moses Sofer, the leader of orthodox Jewry in the first part of the nineteenth century, similarly ruled that absence of respiration is conclusive only if the patient “…lies as an inanimate stone and there is no pulse whatsoever."

Rabbi Bleich is also unconvinced by the "physiological decapitation” argument of those who find brain death to be halakhically acceptable. Just as decapitation involves separation of the entire head from the body, so too "physiological decapitation" must be defined as physiological destruction of the entire brain. This phenomenon has never been observed. Moreover, he maintains that the halakha does not equate dysfunction of an organ with its excision. For example, an animal with “no liver” may not be eaten (though note, there is no such reality as an animal with “no liver”); but an animal in which there is a liver, however poor its function, is considered kosher. So too, the failure of the brain to function cannot be equated with its excision, and the patient with brain death is not analogous to a decapitated individual, in whom the heartbeat is most certainly not a sign of life. Moreover, it is still unclear what proportion of the brain is destroyed at the time brain death is diagnosed. As one physician wrote:

In the usual clinical context of brain death there is no certain way of ascertaining (other than by angiographic inference) that major areas of the brain such as the cerebellum, the basal ganglia, or the thalami have irreversibly ceased to function. A clinical diagnosis of "whole brain death" is in this sense a fiction.

Rabbi Bleich's criticisms of the brain death criteria were supported by Rabbi Ahron Soloveichik (d. 2001) who was Rosh Yeshivah of Brisk Yeshiva in Chicago, and a leading halakhic figure in the United States, who wrote that

“…according to the halakha total death [sic] is determined by termination of the three basic functions of life; namely respiration, cardiac activity and brain function ... .it is incumbent upon all those who have ethical sensitivity to protest against those who are trying to implement the Harvard criteria.”

Differences of Opinion

The entire debate is made even more perplexing by the different interpretations placed, not only on the Talmudic texts and commentaries, but on the responsa of the late Rabbi Moshe Feinstein. Ever since his death in 1986 his position as a halakhic figure has become of such importance that both those in favor of accepting brain death criteria and those who oppose it have made efforts to show that he would have supported their respective claims. The same responsa are used to demonstrate completely divergent opinions.

In 1976 Rabbi Feinstein wrote a responsa to Rabbi Tendler (who is also his son-in-law,) in which he explained that it was permissible to test for evidence of spontaneous respiration in a patient on a respirator, during the time the respirator is disconnected to allow the patient's airways to be suctioned (אגרות משה - יורה דעה חלק ג' סימן קלב). If no respiratory efforts are observed over a fifteen-minute period, the patient may be declared dead. Rabbi Feinstein added that radioisotope studies, used as a measure of brain blood flow, should be used to confirm brain death. Tendler and Rosner cite this responsa as evidence that Rabbi Feinstein supported the concept of physiological decapitation, and suggest that radioisotope studies are not obligatory but should be used if available. Steinberg also cites this responsa, and emphasized that nowhere does it mention cardiac cessation as a criteria of death, which would clearly support the brain death criteria. However, Bleich and Abraham both reject this interpretation as being highly incompatible with previous responsa of Rabbi Feinstein, and claim instead that blood flow studies are to be undertaken before certifying death, even in the absence of respiration. This responsa is believed by those opposed to the brain death criteria to show that respiratory criteria are not to be relied on, and that Jewish law is not compatible with such standards. A similar disagreement over the meaning of Rabbi Feinstein's analysis exists over at least two other responsa.

Long ago, the Israeli Chief Rabbinate published its position on the acceptability of the brain death criteria following an inquiry made by the Israeli Ministry of Health regarding the initiation of a heart transplant program. Their findings, which permitted heart transplants at Jerusalem's Hadassah hospital, were based the determination of death as recommended by a committee of physicians at the hospital; the Chief Rabbinate accepted brain death as halakhic death, although it did require an additional confirmatory test of brain stem dysfunction.

when You need to decide….

The definition of death clearly is not a matter of even remote agreement among Jewish scholars. For them, determination of death need not necessarily be of practical importance. For the Jewish doctor, however, faced with the decision in the Intensive Care Unit as to whether or not a patient has died, and whether another may receive life-saving organs, the matter is of the utmost urgency. Perhaps all the doctor can be expected to do is to understand fully the debate, and know on whose opinion her actions are based. If the doctor chooses to declare the patient dead based on the brain death criteria accepted by the Conference of Medical Royal Colleges, then she has a number of leading halakhic authorities on which to rely. If however, the doctor feels uneasy about declaring the patient dead whilst there is still cardiac activity, and would rather wait a few days until spontaneous cessation of the heart she too has a halakhic basis on which to rely, though to be honest her medical colleagues may not agree. For the observant Jewish physician, the decision must ultimately be based on the doctor's careful understanding of the halakhic difficulties with both positions, together with Rabbinic guidance of the highest expertise.