ISRAELI NOBEL PRIZE WINNERS FOR $200 PLEASE, ALEX

Quick. Name three Israelis who have won a Nobel Prize. Come on. You can do this. Still need a hint? Click here. See, I told you you'd know.

OK, those were easy. How about this one. Which Israel won a Nobel Prize for literature? Need a hint? He was awarded it in 1966 for "his profoundly characteristic narrative art with motifs from the life of the Jewish people" and his photo is shown here. Still not sure? You may have read his work on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur which was translated into English as Days of Awe...Of course; it was Shai Agnon, who was born in Galicia, moved to what was then Palestine (twice) and died in Jerusalem in 1970.

As of this year there have been twelve Israeli winners of the Nobel Prize. We've noted Agnon as the single winner for literature, and (as you may have answered correctly) there have been three winners of the Nobel Peace Prize: Menachem Begin (1978), Yizhak Rabin and Shimon Peres (both in 1994). That leaves eight more prizes. In honor of Yom Ha'atzmaut, Israel's Independence Day, we will pause from our analysis of science in the Talmud and reflect on the Israeli winners of this prize, given each year (in accordance with the will of Alfred Nobel) "to those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind."

DANIEL KAHNEMAN, ECONOMICS, 2002

Following at an eight year prize-drought, Israel picked up her fifth Nobel in 2002, when Daniel Kahneman was awarded the 2002 Prize in Economics. In his biographical sketch, Kahneman credits his early days in the IDF with the first cognitive illusion he discovered.

““… after an eventful year as a platoon leader I was transferred to the Psychology branch of the Israel Defense Forces….We were looking for manifestations of the candidates’ characters… we felt…we would be able to tell who would be a good leader and who would not. But the trouble was that, in fact, we could not tell... The story was always the same: our ability to predict performance at the school was negligible...I was so impressed by the complete lack of connection between the statistical information and the compelling experience of insight that I coined a term for it: “the illusion of validity.” Almost twenty years later, this term made it into the technical literature. It was the first cognitive illusion I discovered.”

(I was about two-thirds of the way through Kahneman's recent best-seller Thinking Fast and Slow, when I left it on a flight from Tel Aviv. Please let me know if you find it.)

CIECHANOVER AND HERSHKO, CHEMISTRY 2004

In 2004 Aaron Ciechanover and Avram Hershko, both from the Technion in Haifa (together with Irwin Rose), were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their discovery of how cells breaks down some proteins and not others. They discovered ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, a process where an enzyme system tags unwanted proteins with many molecules of another protein called ubiquitin. The tagged proteins are then transported to the proteasome, a large multi-subunit protease complex, where they are degraded.

ROBERT AUMANN, ECONOMICS, 2005

Robert Aumann from the Hebrew University won the 2005 Nobel Prize in Economics for his work on conflict, cooperation, and game theory (yes, the same kind of game theory made famous by John Nash, portrayed in A Beautiful Mind). Aumann worked on the dynamics of arms-control negotiations, and developed a theory of repeated games in which one party has incomplete information. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences noted that this theory is now "the common framework for analysis of long-run cooperation in the social science." The kippah-wearing professor opened his speech at the Nobel Prize banquet with the following words (which were met with cries of אמן from some members of the audience):

ברוך אתה ה׳ אלוקנו מלך העולם הטוב והמיטב

The four-minute video of his talk should be required viewing for every Jewish high school student (and their teachers).

ADA YONATH, CHEMISTRY, 2009

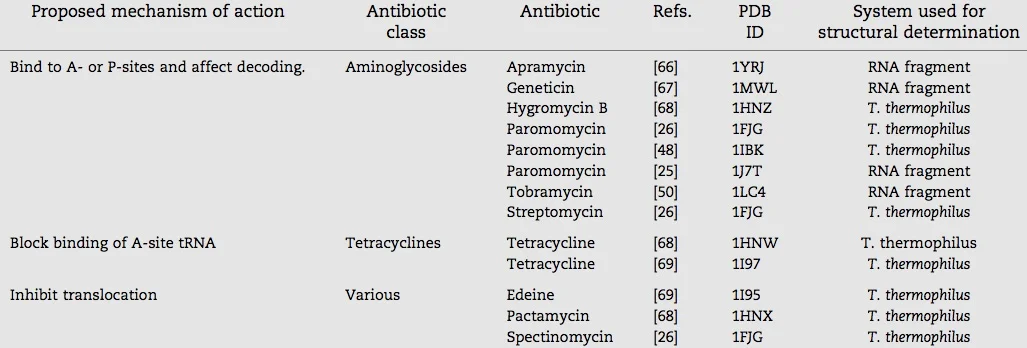

Remember ribosomes from high school? They are the machines inside all living cells that read messenger RNA and link amino acids in the right order to make proteins. In 2009, Ada Yonath from the Weizmann Institute shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her work on the structure and function of the ribosome. Specifically, she reported their three-dimensional structure and her work in the 1980s was "instrumental for obtaining the robust and well diffracting ribosome crystals that eventually led to high resolution structures of the two ribosomal subunits." Why is this important? Well, many antibiotics target the ribosomes of bacteria, and so knowledge of how antibiotics bind to the ribosome may help in the design of new and more efficient drugs.

Available structures of antibiotics targeting the small ribosomal subunit (30S). From Franceschi and Duffy. Structure-based drug design meets the ribosome. Biochemical Pharmacology 2006; 71; 1016-1025.

DAN SHECHTMAN, CHEMISTRY, 2011

in 1982, Shechtman was working at the US. National Institute of Standards and Technology. As he was looking through an electronic microscope at the structure of new material that he was studying, and noted that the atoms had arranged themselves "in a manner that was contrary to the laws of nature."

אין חיה כזו – There is no such entitiy" was how he recalled responding to what he had seen. Shechtman double checked his findings and submitted them for publication; the paper was rejected immediately, not worthy even of being sent on for peer review. But Shechtman did manage to get his work published, work that the Nobel Committee found questioned a fundamental truth of science: that all crystals consist of repeating, periodic patters. Shechtman's discovery of what were later to be called quasicrystals was important not only because of what he found. It was important that he found. Here's why:

“Over and over again in the history of science, researchers have been forced to do battle with established “truths”, which in hindsight have proven to be no more than mere assumptions. One of the fiercest critics of Dan Shechtman and his quasicrystals was Linus Pauling, himself a Nobel Laureate on two occasions. This clearly shows that even our greatest scientists are not immune to getting stuck in convention. Keeping an open mind and daring to question established knowledge may in fact be a scientist’s most important character traits.”

ARIEH WARSHEL AND MICHAEL LEVITT, CHEMISTRY 2013

Israelis continued with a winning streak at chemistry. In 2013 Arieh Warshel and Michael Levitt shared the prize in, yes, Chemistry, (together with Marin Karplus, a Jew, but not yet an Israeli). Working together in the 1970s on GOLEM, the supercomputer at the Weizmann Institute, they developed computer programs that could simulate chemical reactions with the help of quantum physics. These programs, and their offshoots, are used in a variety ways, from optimizing solar panels to designing new drugs.

Joshua Angrist, Economics 2021

The most recent Israeli Nobel laureate is Joshua Angrist, who was awarded the 2021 Nobel Prize in Economics. Angrist, who is a professor at The Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was born in the US but lived in Israel in the 1980s, where he served as a paratrooper. He holds dual US-Israeli nationality, and has spent much of his career analyzing the economics of schooling and the effect of class size on academic achievement. One of his papers looks at the “Maimonides Rule,” named for, well, Maimonides, who apparently noted a correlation between class size and student achievement.

THE LAST WORD

There you have it. Thirteen remarkable Israelis who have contributed to peace efforts, science and literature, and whose efforts were recognized by a Nobel Prize. As we celebrate Yom Ha'atzmaut, let's give the last word to the 2005 winner Robert Aumann, who noted in his banquet speech just what is really important in life.

“We have participated in the human enterprise – raised beautiful families. And I have participated in the realization of a 2000-year-old dream – the return of my people to Jerusalem, to its homeland.”