Today’s page of Talmud continues a discussion of who may be taught about Ezekiel’s vision of the Chariots, known in Hebrew as Ma’aseh Merkavah. The vision is found in the first chapter of the Book of Ezekiel and describes a four-wheeled chariot driven by four hayyot ("living creatures"), each of which has four wings and four faces; one of a human, one of a lion, one of an ox, and one of an eagle (or possibly a vulture).

The Mishnah (11b) has ruled that this section may never be taught to another person; instead it can only be studied by one “ who is wise and understands most matters on his own” (הָיָה חָכָם וּמֵבִין מִדַּעְתּוֹ)

One of the verses included in Ma’aseh Merkavah is this one, from Ezekiel 1:4:

וָאֵרֶא וְהִנֵּה רוּחַ סְעָרָה בָּאָה מִן־הַצָּפוֹן עָנָן גָּדוֹל וְאֵשׁ מִתְלַקַּחַת וְנֹגַהּ לוֹ סָבִיב וּמִתּוֹכָהּ כְּעֵין הַחַשְׁמַל מִתּוֹךְ הָאֵשׁ׃

I looked, and lo, a stormy wind came sweeping out of the north—a huge cloud and flashing fire, surrounded by a radiance; and in the center of it, something like chasmal, from the fire.

Rashi explains that the word chashmal refers to an angel:

כעין החשמל. חשמל מלאך ששמו כך וכעין גוון שלו ראה מתוך האש

it was like the color of the chashmal “Chashmal” is an angel bearing that name, and he [Ezekiel] saw something like the appearance of its color in the midst of the fire.

This strange word chashmal appears one other time in this chapter, in verse 27:

וָאֵרֶא כְּעֵין חַשְׁמַל כְּמַרְאֵה־אֵשׁ בֵּית־לָהּ סָבִיב מִמַּרְאֵה מׇתְנָיו וּלְמָעְלָה וּמִמַּרְאֵה מׇתְנָיו וּלְמַטָּה רָאִיתִי כְּמַרְאֵה־אֵשׁ וְנֹגַהּ לוֹ סָבִיב׃

From what appeared as his loins up, I saw a gleam chashmal, what looked like a fire encased in a frame; and from what appeared as his loins down, I saw what looked like fire. There was a radiance all about him.

On today’s page of Talmud we read this:

חגיגה יג, א–ב

מַאי חַשְׁמַל? אָמַר רַב יְהוּדָה: חַיּוֹת אֵשׁ מְמַלְּלוֹת

What is chashmal? Rav Yehuda said: It refers to speaking animals of fire. Chashmal [chashmal] is an acrostic of this phrase [chayyot esh memallelot].

While the meaning of this strange word chashmal in Ezekiel’s vision is unclear, today, the word has a very clear meaning. It is the modern Hebrew word for electricity. On today’s Talmudology, we will explore how this modern word was derived from Ezekiel’s mystical vision.

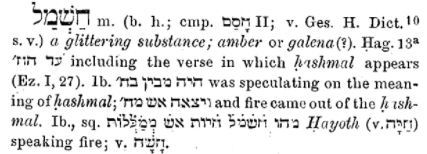

Chasmal and - The “Electrum”

The ArtScroll English translation of the Talmud translates the word chashmal as, well, chashmal, which is fair enough, since we don’t know what it means. But the Koren Talmud does translate the word. It translates it as “electrum.” This is an interesting choice, because in his original Hebrew commentary, the late Rabbi Adin Steinzaltz, on whom the Koren edition is based, did not explain the meaning of chashmal. Did the Koren translators work backwards from the modern Hebrew meaning chashmal as electricity? If so, that would not be a very reasonable choice. But this seems unlikely.

Marcus Jastrow, in his classic dictionary, translated the word as amber, which is also the translation used by the Jewish Publication Society’s 1985 english translation of the Bible.

Time for A Greek Lesson

Perhaps the Koren based its translation on another ancient text known as the Septuagint, a Greek version of the Hebrew Bible that was written anonymously some time between the third and second centuries BCE.

In the Septuagint, the word chashmal is translated as the second declension count ηλεκτρου - elektron, which does not have the modern connotation of electricity. Instead, it means amber, and hence Jastrow’s translation. The word is connected to another Greek word ηλεκτωρ - elektor, meaning "beaming Sun." In Latin, the word is translated as electrum, which is likely where the Koren translation picked it up. (If you are one of the Koren translators, please write to Talmudology with the full story. We will share it with our readers.)

In any event, amber is not only a color; it is the name of a gemstone made from fossilized tree resin. According to Greek myth, when Phaeton, the son of Helios the sun god was killed (it’s a long story), his mourning sisters became poplar trees, and their tears became elektron, giving us amber. Over the centuries it was noted that this amber could attract things like leaves and feathers to its surface. Today, we recognize the cause of this as static electricity, but back then objects, like amber, that had this property were said to be electric. Apparently, the first time the word appears in English was when it was used by by English physicist William Gilbert (1540-1603) in his treatise "De Magnete" (1600). We soon had the word electrical, meaning "giving off electricity when rubbed.”

ChaSMAL as Electricity in the Writings of Yehudah Leib Gordon

As this new word spread into Europe, it also entered the Yiddish lexicon, where electricity was called, unsurprisingly electric, (עלקטעריק). And so things remained until “the most important Hebrew poet of the nineteenth century,” Yehudah Leib Gordon (1831–1892), decided that the Jewish people could do better. In a very (very, very) long poem called Two Yosef ben Shimon (which is itself a play on the words of the Talmud from Gittin 24b) Gordon wrote this beautiful verse

וּכְמוֹ הַהֲלָכָה בְּמַעֲשֶׂה־בְּרֵאשִׁית נִשְׁלָבָה

כֵּן נוֹסְדָה הַקַּבָּלָה עַל מַעֲשֵׂי־מֶרְכָּבָה

מָה הַסְּפִירוֹת אִם לֹא גַּלְגִּלֵּי שָׁמָיִם

הָאוֹר, הַחֹם, הַקִּיטֹר, הַחַשְׁמַלָּה

כָּל כֹּחוֹת הַטֶּבַע הֵם מַלאֲכֵי מַעְלָה

יֵדָעוּם הַחוֹקְרִים גְּלוּיֵי־הָעֵינָיִם

…What are the mystical sephirot, if not the layers of heaven

Light, heat, the streaming [?] and electricity [hachashmala]

On June 28, 1974, the Hebrew newspaper Davar published an article on the origin of the word chashmal. It claimed that in a footnote to his poem, Gordon wrote

כוונתי להכוח הטבעי הנקרא עלעקטריציטעט, שכן התרגום היווני של חשמל הוא עלעקטרא

I am referring to the natural phenomenon called electricity, for the Greek translation of the word “chashmal” is “electra.”

And so a new word was born in modern Hebrew. Electricity would now be known as chashmal.

(By the way, it is worth noting that another early Hebrew poet, Yehuda Leib Katzenelson (1846-1917), who wrote under the pen-name Buki Ben Yogli, also used the word chashmal, only his meaning did not catch on. In a short story titled The Olive and the Chasmal, he used it to mean the light that is reflected from olive oil.)

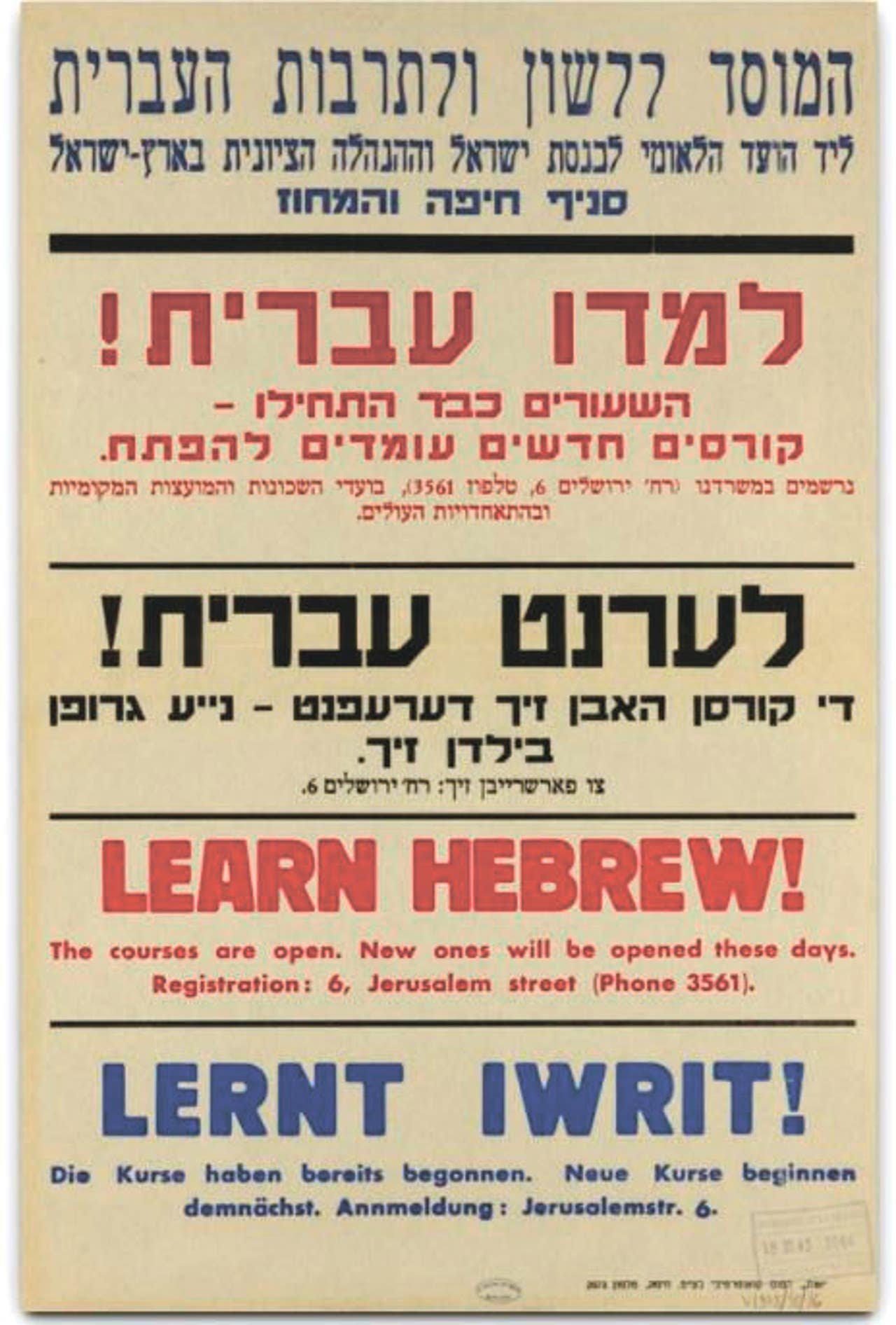

The Palestine Electric Company

Pinchas Rotenberg (1879-1942) founded the Palestine Electric Company in March 1923, and called it Chevrat Hachashmal Palestina (חברת החשמל פלשתינה). It was recognized by the British Mandate Authority, had its headquarters in London, and was traded on the London Stock Exchange. It later became the Israel Electric Company. With this, the word entered the modern Hebrew lexicon.

summary

The word Chashmal is used in Ezekiel’s vision but its meaning is not certain. Perhaps refers to an angel (per Rashi) or to a color (also per Rashi).

In the Greek Septuagint, the word chashmal is translated as elektron, meaning an amber color. This is also how Jastrow translated the word.

In the seventeenth century, the word electra was introduced by William Gilbert. It came to mean “giving off [static] electricity when rubbed.”

In a sort of back translation from the Greek, the nineteenth century Hebrew language poet Yehudah Leib Gordon used the word chashmal mean electric in the modern sense that we use it today.

In 1923 the Chevrat Hachashmal Palestina was founded by Pinchas Rotenberg, and the word chashmal entered modern Hebrew.

The resurrection of the dry bones

Ezekiel had another famous vision. It was the resurrection of the dry bones that appears in chapter 37, and describes how God re-animated the dead.

יחזקאל 37:14

וְנָתַתִּי רוּחִי בָכֶם וִחְיִיתֶם וְהִנַּחְתִּי אֶתְכֶם עַל־אַדְמַתְכֶם וִידַעְתֶּם כִּי־אֲנִי יְהֹוָה דִּבַּרְתִּי וְעָשִׂיתִי נְאֻם־יְהֹוָה׃

I will put My breath into you and you shall live again, and I will set you upon your own soil. Then you shall know that I the Lord have spoken and have acted”—declares the Lord.

A vision of the Jewish people once again “set you upon your own soil.” And on that soil they used a word from another of Ezekeiel’s prophecies to describe electricity as chashmal. Ezekiel would have been very proud.