Kids Today

In a recent Pew study on the use of electronic media by children in the US was this remarkable finding: Nearly one-in-five parents of a child 11 or younger (17%) say that their child has their own smartphone. Here's another gem from the same report: More than one-third of parents with a child under 12 say their child began interacting with a smartphone before the age of 5. Some children have quite comfortable lives, it would seem. But it wasn't always that way.

Kids Back Then

Today's page of Talmud (Ketuvot 50a) reminds us of another kind of reality that children once faced. Back then, it was a much more harsh world. And not just because the kids were not given their own iPhone. In fact, according to the Talmud, they were lucky just to get food and shelter.

תלמוד בבלי כתובות דף נ עמוד א

אשרי שומרי משפט עושה צדקה בכל עת - וכי אפשר לעשות צדקה בכל עת? דרשו רבותינו שביבנה ... זה הזן בניו ובנותיו כשהן קטנים

““Happy are those who keep justice, who perform charity at all times” (Psalms 106:3). But is it possible to perform charity at all times? This, explained our Rabbis in Yavneh...refers to one who sustains his sons and daughters when they are minors.”

In yesterday's Daf, we learned that a person's legal obligation to support their children ends when those children reach the age of six. From that age, the parents' obligations to give their children water, food and clothing is not a legal one, but a moral one. If a parent refuses to support a child older than six, the courts can impose pressure to do so. But there is no legal obligation to support your child once they reach the ripe old age of six. Because of this ruling, the Talmud considers the support of minor children to be an act of charity. (Try bringing that argument up the next time your child asks for a cellphone upgrade.) Here is how this law is codified.

שולחן ערוך אבן העזר הלכות כתובות סימן עא סעיף א

חייב אדם לזון בניו ובנותיו עד שיהיו בני שש ...ומשם ואילך, זנן כתקנת חכמים עד שיגדלו. ואם לא רצה, גוערין בו ומכלימין אותו ופוצרין בו. ואם לא רצה, מכריזין עליו בצבור ואומרים: פלוני אכזרי הוא ואינו רוצה לזון בניו, והרי הוא פחות מעוף טמא שהוא זן אפרוחיו; ואין כופין אותו לזונן...במה דברים אמורים, בשאינו אמוד, אבל אם היה אמוד שיש לו ממון הראוי ליתן צדקה המספקת להם, מוציאים ממנו בעל כרחו, משום צדקה, וזנין אותם עד שיגדלו

A person is obligated to support his sons and daughters until they reach the age of six...From that age, he is required by rabbinic decree to support them until they grow up. If he does not wish to support them, we admonish him until he complies. If he still refuses, we announce to the public: "So-and-so is a cruel person, and does not wish to support his children. He is worse than an unclean bird - even that bird cares for its chicks." But we cannot force him to support his children.

But this only applies when we have assessed that indeed he cannot support them financially. But if we assessed him, and found that he has the money to give to charity and this would allow the children to live, we take the money from him by force, in the name of charity, and support the children until they grow up. (Shulchan Aruch Even Ha'Ezer 71:1)

The Economic Costs of Raising Children

Raising children is an expensive undertaking. It requires parents to put in years and years of emotional, material and psychological effort. Those material costs can be calculated, and here they are:

So according to the USDA, it costs - on average - about $241,000 to raise a child in the US. That sounds like a bargain to me. It cost that just to put one of my children through through twelve years of their Jewish school. And that's before I'd bought them a slice of bread. Or an iPhone.

Families Projected to Spend an Average of $233,610 Raising a Child Born in 2015. From here.

“For someone making $60,000 a year, in America, that’s middle class...But in this Orthodox community, $60,000 means you aren’t going to make it.”

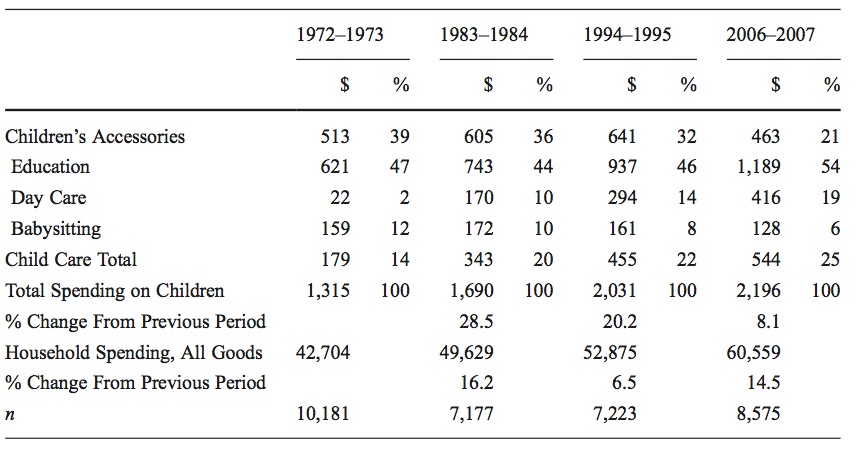

Research by the sociologists Sabino Kornrich and Frank Furstenberg has demonstrated that the way Americans spend money on their children has changed over the last several decades. It turns out that before the the 1990s, parents spent most on children in their teen years. However, after the 1990s, spending patterns shifted, and was greatest when children were under the age of 6 and in their mid-twenties. We've also changed the where we spend on our children - and education now accounts for more than half of what US parents spend on their children.

Average spending per child by year and percentage of expenditures in each area for all households with children age 0 to 24. From Kornrich and Furstenburg. Investing in Children. Demography 2013. 50:1-23.

There's some good news too, for girls. In the 1970s, parents in households with only male children spent significantly more than parents in households with only female children - and nearly all of that extra money was spent on education. But by the early 2000s, the data showed a reversal: households with only female children spent more than households with only male children.

Kronrich and Fursetnberg concluded that parents are investing more heavily in their children now than in the past. "While scholars debate exactly which resources matter most for children’s development... parents are demonstrating a substantial willingness to spend in order to better their children’s circumstances. These results mirror other shifts in parental behavior: parents are having fewer children and, through a range of activities like spending time with their children and choosing activities that impart cultural capital, are investing more intensively in the children they do have."

Treat Your Children Well

Jewish law considers the support of a child to be an act of charity rather than a legal obligation. There is a similar ruling that shows an interesting symmetry at the other end of the spectrum. The Shulchan Aruch (הלכות צדקה סימן רנא) writes

וכן הנותן מתנות לאביו והם צריכים להם, הרי זה בכלל צדקה

... a child who gives a gift to his parent who needs it, can include this as an act of charity

Just as you are not legally obligated to support your children when they are young, your children have no legal obligation to support you in your old age. If they choose to do so, their act is one of charity. So treat your children well; they'll be the ones who will choose your nursing home.

“Spending on children is one of the most direct ways that parents can invest in children. Parental spending can buy children experiences that build human and cultural capital: high-quality education, residence in better neighborhoods, and potentially high-quality child care while children are young and parents are at work.”