In this week’s parsha, we read about the rewards for following the word of God. And then we read about the punishments for not doing so. Here is one of the latter:

דברים כח: 15,27

וְהָיָה אִם־לֹא תִשְׁמַע בְּקוֹל יְהֹוָה אֱלֹהֶיךָ לִשְׁמֹר לַעֲשׂוֹת אֶת־כל־מִצְותָיו וְחֻקֹּתָיו אֲשֶׁר אָנֹכִי מְצַוְּךָ הַיּוֹם וּבָאוּ עָלֶיךָ כל־הַקְּלָלוֹת הָאֵלֶּה וְהִשִּׂיגוּךָ׃

…יַכְּכָה יְהֹוָה בִּשְׁחִין מִצְרַיִם ובעפלים [וּבַטְּחֹרִים] וּבַגָּרָב וּבֶחָרֶס אֲשֶׁר לֹא־תוּכַל לְהֵרָפֵא…

But if you do not obey the Lord your God to observe faithfully all His commandments and laws which I enjoin upon you this day, all these curses shall come upon you and take effect…The Lord will strike you with the Egyptian inflammation, with hemorrhoids, boil-scars, and itch, from which you shall never recover.

The word translated as hemorrhoids is written “עפלים,” but that is not what you will hear being chanted. Instead, you will hear the word “טְּחֹרִים.” If you have you wondered why, you are in luck, because this week in Talmudology on the Parsha we will discuss the kri and the ketiv. Oh, and also hemorrhoids.

A Quick Introduction to Kri & Ketiv

There are two traditions that we have about the written Torah, also known as the Five Books of Moses. There is the way the word is written - known as the ketiv, from the Hebrew k-t-v (כ–ת–ב), meaning, well, written, And there is the way that the word is actually pronounced, known as the kri, from the Hebrew k-r-i (ק–ר–י), meaning read.

If Jewish services are familiar to you, then so too is the kri-ketiv. There is one that is said often, and certainly each time we read it in the Torah. It is the name of God, spelled in the Torah in Hebrew as י–ה–ו–ה. It is pronounced something like Yehowah, from where we get the word Jehovah, (as in Witnesses). But whenever we encounter that word in the Torah, or as part of Jewish prayer, we pronounce it Adonai (lit. my Lord). See. It’s a kri-ketiv.

Emanuel Tov, Professor Emeritus of Bible at the Hebrew University (and the editor-in-chief of the Dead Sea Scrolls publication project) is probably the world's leading authority on the textual criticism of the Hebrew. In his classic work Textual Criticism of the Hebrew Bible (I have the second edition, but a third is now available,) he noted that there are anywhere from 848 to 1566 instances of kri-ketiv, depending on which text you consult. (He and other academics rather annoyingly calls them Ketib-Qere, but I suppose if you are the world expert you get to do that kind of thing.)

The notion of the Ketib and Qere in the manuscripts of [the masoretic text] derives from a relatively late period, but the practice was already mentioned in the rabbinic literature…For example, b. Erub. 26 a motes that in 2 Kgs 20:4 “it is written ‘the city,’ but we read ‘court.’ Manuscripts and editions likewise indicate: Ketib העיר, “the city,” Qere חצר, “court.” (p59.)

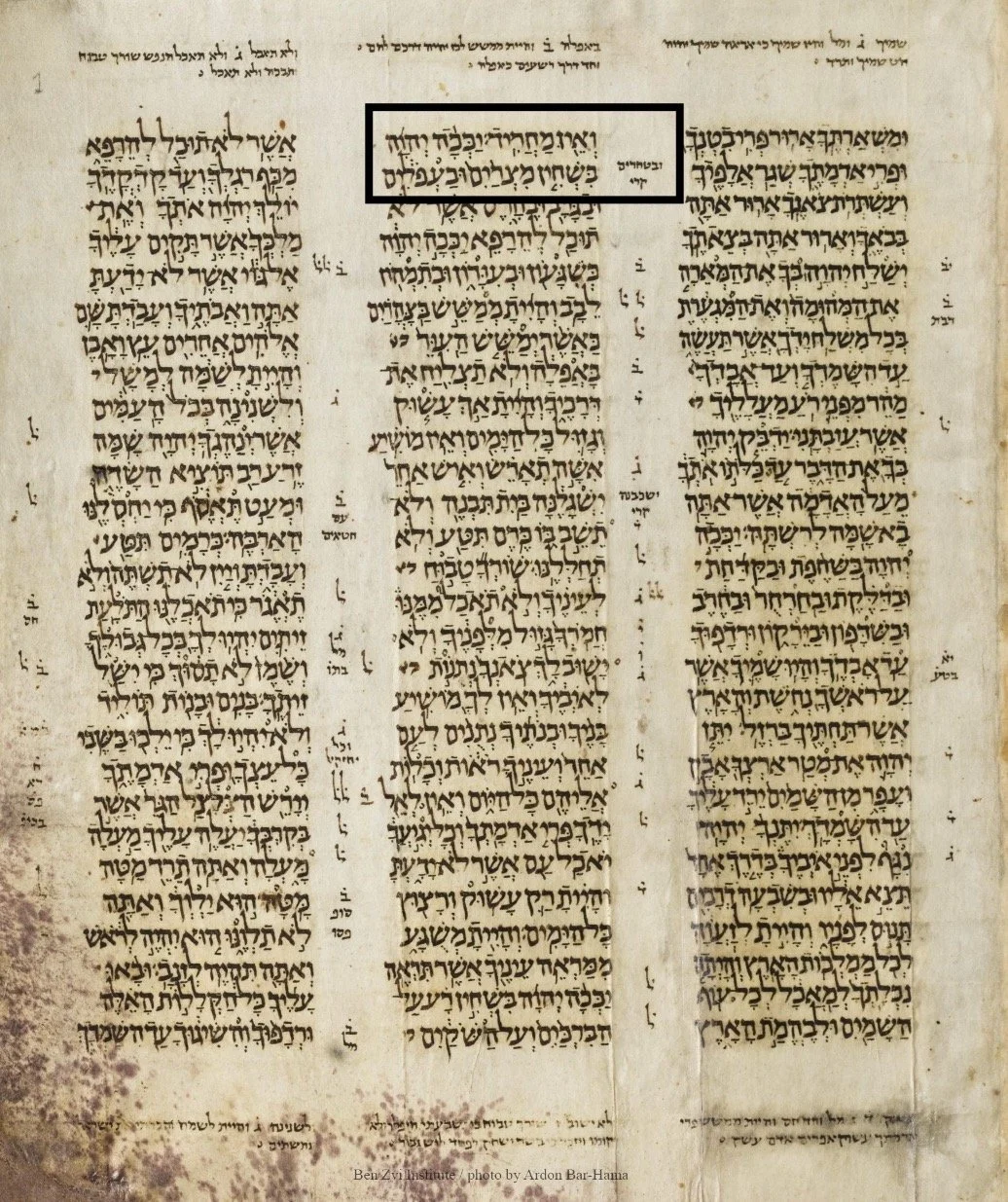

The Aleppo Codex, (c. 920 CE) Ki Tavo. The subject matter of this post is found in the black box, and the note on the keri is found in the marginalia to its right.

The Origins of the Keri-Ketiv

Summarizing the scholarship, Emanuel Tov suggested four possible origins of the kri-ketiv:

They are corrections

They are variant spellings

They are marginal corrections that later became variant spellings

They are reading traditions

Most scholars adhere to the third reason. “If that view is correct,” he wrote, “most of the Ketib-Qere interchanges should be understood as an ancient collection of variants. Indeed, for many categories of Ketib-Qere interchanges similar differences are known between ancient witnesses [i.e. very old manuscripts].

Sometimes the keri-ketiv avoids profanation, such as the perpetual reading of God’s four-letter name as Adonai. And sometimes they serve “as the replacement of possibly offensive words with euphemistic expressions.” This is what is going on in this week’s parsha, where ובעפלים (and with hemorrhoids) is replaced with וּבַטְּחֹרִים (and with tumors). The Talmud makes this cleaning up of the text explicit:

מגילה כה, ב

תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: כל הַמִּקְרָאוֹת הַכְּתוּבִין בַּתּוֹרָה לִגְנַאי — קוֹרִין אוֹתָן לְשֶׁבַח, כְּגוֹן: ״יִשְׁגָּלֶנָּה״ — יִשְׁכָּבֶנָּה, ״בַּעֲפוֹלִים״ — בַּטְּחוֹרִים, ״חִרְיוֹנִים״ — דִּבְיוֹנִים, ״לֶאֱכוֹל אֶת חוֹרֵיהֶם וְלִשְׁתּוֹת אֶת מֵימֵי שִׁינֵּיהֶם״ — לֶאֱכוֹל אֶת צוֹאָתָם וְלִשְׁתּוֹת אֶת מֵימֵי רַגְלֵיהֶם

The Sages taught in a baraita: All of the verses that are written in the Torah in a coarse manner are read in a refined manner. For example, the term “shall lie with her [yishgalena]” (Deuteronomy 28:30) is read as though it said yishkavena, which is a more refined term. The term “with hemorrhoids [bafolim]” (Deuteronomy 28:27) is read bateḥorim. The term “doves’ dung [chiryonim]” (II Kings 6:25) is read divyonim. The phrase “to eat their own excrement [choreihem] and drink their own urine [meimei shineihem]” (II Kings 18:27) is read with more delicate terms: To eat their own excrement [tzo’atam] and drink their own urine [meimei ragleihem].

So that explains why the word ובעפלים is read as וּבַטְּחֹרִים. But why are these kinds of swellings mentioned among the curses that await the Israelites if they fail to heed the word of God? Is that the best punishment that God can come up with? Well, it turns out that ophalim likely referenced a truly awful punishment, one that would instill dread and fear. I am talking about bubonic plague.

More than You ever wanted to know about Biblical Hemorrhoids

Let’s fast forward to the Book of Samuel. Having entered the Promised Land, the people of Israel began a long military campaign against its inhabitants, the foremost of which were the Philistines. But they lost not only their battles, but also their Ark, which had been brought to the battlefield in a last-ditch attempt at victory. The captured Ark was taken to Ashdod and placed in a temple to Dagon. God then directed his anger against the Philistines in a most unusual way. He destroyed the idols in the temple and then “struck Ashdod and its territory with swellings” (I Sam 5:6). When the Ark was moved to Gath, another outbreak of “swellings” followed: “The hand of the Lord came against the city, causing great panic; He struck the people of the city, young and old, so that swellings broke out among them” (I Sam 5:9).”

Having understood the terrible danger of keeping the Ark captive, the Philistines sent it back to Israel, but were counseled by their priests not to “send it away without anything; you must also pay an indemnity to Him.” This reparation took a most unusual form: “five golden swellings and five golden mice” (I Sam 6:4). Just what these swellings were is not clear, but there are two possibilities. The first is they were lymph glands in the groin, swollen from infection from bubonic plague. The second is they were hemorrhoids. Both possibilities are hinted to in the Hebrew text and its many translations.

Plague and Bubos

These two quite distinctive words in our parsha - עפלים and טְּחֹרִים have led to the differing explanations of the epidemic. The identification of the Philistine epidemic as bubonic plague privileges the written text, עפלים ophalim. Bubonic plague got its name from the buboes, which are swellings in the axillae and groin. These are the lymph nodes that swell with bacteria and the body’s own dead cells white cells. Bubonic plague is caused by a bacterium called Yersinia Pestis, which is found in fleas that primarily feed on mice and rats, though they can also leap to humans. It swept through Europe as the Black Death in a series of deadly waves that began around 1347, killing a third of the population. But it was also around long before then; fragments from an ancestor of Yersina Pestis have been detected in samples over 3,000 years old.

The Hebrew Bible doesn’t mention the role of rodents in spreading the epidemic, but the Greek translation known as the Septuagint does. This translation was composed around the third century B.C.E. for the Jews of Alexandria, and it adds a detail not found in the Hebrew original: “And the Ark was seven months in the country of the Philistines, and their land brought forth swarms of mice.” These “swarms of mice,” missing from the Hebrew text, are a key to identifying the epidemic. Rodents play a key role in the transmission of bubonic plague. It was these swarms of mice (or really rats, which are the primary host for the rat flea that carries the plague bacteria Yersinia) that were responsible for spreading the plague among the Philistines, causing the lymphatic swellings that characterize the bubonic plague.

One of the first people to identify the outbreak as bubonic plague was the Swiss naturalist Johan Jakob Scheuchzer, who died in 1733. Scheuchzer’s many works included the four-volume Latin Physica Sacra, where he noted that ophalim were buboes. “I therefore come to the conclusion,” he wrote, “that the disease which cased so many deaths among the Philistines was real plague.” But Sheuchzer’s written works were predated by the artist Nicolas Poussin (1594– 1665), whose painting The Plague of Ashdod became “the most imitated and celebrated plague painting of the seventeenth century.”

Nicolas Poussin, The Plague of Ashdod, 1630. From here.

Poussin’s painting shocks. At the foot of the painting lie a dead woman and child, their skin already a pallid green. Another child tries in vain to suckle from the breast of her dead mother. From there we are drawn to the onlookers and those in the throes of death, while in the background bodies are carried away. All around are the rodents, fearless as they come out of their lairs into the daylight. Several figures are pinching their noses to keep out the awful odor from the buboes that had ruptured, while a group looks in dismay at the broken idols in what had been the temple of Dogon. Poussin knew of what he painted for in 1630, the same year in which he began this work, Italy suffered a terrible outbreak of the plague.

Poussin was one of several artists who depicted the Philistine plague. Mice can be seen scurrying over the bodies of four dead Philistines in the lavishly illustrated Crusader Bible created in the mid- thirteenth century. “The victims here lie heaped,” wrote the art historian Otto Neustatter, “but otherwise show no specific signs of the plague, the great ravages of which swept over Europe a century later. Rats, however, swarm from every nook and cranny of the crowded city buildings and attack the bodies and faces of the victims.” And in a woodcut in the Lutheran Lubeck Bible, printed in 1491, “the mice play an especially prominent part.” Although the bacterium that caused bubonic plague was not identified until the mid- nineteenth century, the association of rodents in spreading the disease had long been acknowledged, starting perhaps with the Hebrew Bible itself.

So what were Tehorim?

While modern germ hunters gave primacy to the written text ophalim, rabbinic interpretations of the story focused on the word that was read in its place, tehorim, and first, they had to establish its precise meaning. However, over the centuries there has been little agreement. For Josephus, a first- century Roman Jew, the plague was “dysentery or flux; a sore distemper, that brought death upon them very suddenly.” A millennium later, the medieval French commentator Rabbi Shlomo ben Yitzhak (d.1105) had a different idea. Rashi, as he was known by his acronym, was certain that tehorim affect the rectum, but he then needed to explain how this condition was associated with rodents. So he came up with this: “mice enter through rectum, disembowel the innards, and leave.” Two centuries later, another French exegete Levi ben Gershon (Gersonides) focused on the reason for this choice of divine retribution: “Hemorrhoids are very painful, and they bleed a great deal. And how much more so these, that were sent by God to cause them agony. As a result, they would be forced to send the Ark of God away.” In contrast, David Altschuler of Prague (d. 1769) thought that tehorim was the name of a kind of vermin, while the nineteenth-century philologist Marcus Jastrow wrote that the word is derived from the root ט–ח–ר (t-h-r,) meaning to strain.

Later scholars added their own take on the plague of hemorrhoids. Chaim Yosef Azulai (d. 1806), a prominent rabbi and author was born in Jerusalem, but traveled extensively throughout Europe. In his commentary, he wrote that the Philistines had erred, believing in “their own power and the might of their hands.” They were therefore punished with hemorrhoids “that made them appear like women, since they were in pain and were bleeding as women did.”

חומת אנך שמואל א, 5:6

ויך אותם בטחורים. לפי שטעו לומר שכחם ועוצם ידם עשתה זאת הוכו בטחורים שנדמו לנשים בהיותם כואבים ויוצא הדם כי דרך נשים להם

Some contemporary commentaries have tried to combine the two possibilities into a single narrative. The multivolume Olam Hatanach [The World of the Bible] noted that hemorrhoids may be caused by constipation, and that among the causes of this “the medical literature has identified the buboes found in bubonic plague. Thus, the difference between the keri [what is read] and the ketiv [what is written] is the difference between the ophalim [swellings] as a cause of the illness, and tehorim [hemorrhoids] which were its result.” However, this attempt at reconciliation is forced. Bubonic plague may cause constipation, and just as often it may result in diarrhea. To suggest that hemorrhoids are so identified with bubonic plague that they would be specifically mentioned as a feature of the outbreak seems mistaken.

And what of the odd gifts that the Philistines sent, those “five golden hemorrhoids and five golden mice”? This too has its origin not in the original Hebrew but in the Septuagint translation. In Hebrew there were five ophalim or swellings, meaning perhaps five orbs or balls. But in the Greek translation we read, “According to the number of the lords of the Philistines, five buttocks of gold, for the plague was on you, and on your rulers.” From this Greek version of the Hebrew we move to the Latin. In the late fourth century, Jerome produced a Latin translation of the Hebrew Bible known as the Vulgate, which is still used by the Catholic Church. This translation gave us the quinque anos aureos, “five golden behinds,” which was then translated in the King James Bible as “five golden emerods.” The Revised Version of the Bible, first published in 1884, replaced the word emerods with tumors.

In this week’s parsha, God warns his people about the consequences of not obeying his commands. Earlier in the Torah we read of God bringing rivers of blood, darkness, lightening and the parting of the sea as displays of his limitless power. Now, for a change, God threatens to punish in a most intimate and private way, perhaps known only to the unfortunate subject of his anger. Reader beware.

{Want even more on this topic? Try this post. You are welcome.]

![L'atmosphère_-_météorologie_populaire_-_[...]Flammarion_Camille_bpt6k408619m.jpeg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54694fa6e4b0eaec4530f99d/1490796746066-SZ91FZ3ZAN8PSKGAXUKI/L%27atmosph%C3%A8re_-_m%C3%A9t%C3%A9orologie_populaire_-_%5B...%5DFlammarion_Camille_bpt6k408619m.jpeg)