Among the several reasons given by the Talmud for not using the horn of a cow as a shofar, there is this one, stated by the great sage Abayye.

ראש השנה כו, א

שׁוֹפָר אָמַר רַחֲמָנָא, וְלֹא שְׁנַיִם וּשְׁלֹשָׁה שׁוֹפָרוֹת. וְהָא דְּפָרָה, כֵּיוָן דְּקָאֵי גִּילְדֵי גִּילְדֵי — מִיתְחֲזֵי כִּשְׁנַיִם וּשְׁלֹשָׁה שׁוֹפָרוֹת

This is the reasoning of the Rabbis: The Merciful One says to sound a single shofar, and not two or three shofarot together, but this horn of a cow, since it is comprised of layers, looks like two or three shofarot.

Rashi adds explains this passage like this:

גילדי גילדי - בכל שנה ושנה ניכרת תוספתו והוא כמין גלד מוסיף על גלד ראשון בתכליתו של ראשון תחילת השני

It grows in layers: The new growth can be seen every year. It is an additional layer over the first layer with each year adding another.

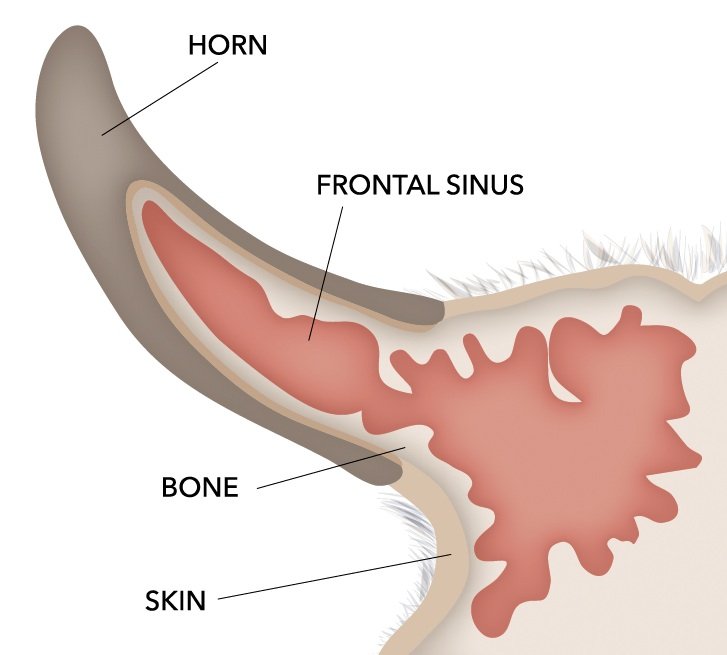

Stages in horn development in cattle(Bos taurus). (A)In the newborn calf there is no tangible protrusion on the skull, but the site of the future horn site is covered by a pair of hairy spots. Beneath the epidermis, mesenchymal structures and sebaceous glands accumulate. Elevation of the underlying frontal bone begins. (B, C) In the juvenile between 2 and 6 months of age a protrusion is visible and the primitive core develops under the epidermis and above the frontal bone. Keratinization has already begun on the epidermis. The core undergoes ossification and then is fused to the underlying protruding (dome-shaped) frontal bone. (D) From 6 months of age to adulthood, the frontal sinus enters the base of the core and pneumatization proceeds until 3 or 4 years of age. Keratinization continues incrementally on the epidermis. *It is not clear at what stage the periosteum is formed around the core bone. In the adult the core bone is overlaid by the periosteum. From Nasoori A. Formation, structure, and function of extra-skeletal bones in mammals. Biol. Rev. (2020).

A helpful paper from the School of Veterinary Medicine in Hokkaido, Japan published last year reviewed the formation, structure, and function of bony compartments like horns (and other bits too) in mammals. It tells you everything you need to know about how reindeer grow their antlers, giraffe their ossicones, and rhinoceri their incredible horns. It also details how cows grow their horns, so it seems the right place to look for help in understanding today’s page of Talmud.

In cattle, the horns begin early in gestation as primitive horn buds, but there is no ossification (the process by which something becomes bone) until after the calf is born. Then, a pair of primitive cores develop above the frontal area (see the figure above, B). These connective-tissue-like cores will later form the bony core of the horn. But these primitive cores have no adhesion to the underlying frontal bone until they fuse with it at around two months of age (C). Subsequently, the core begins to grow upwards and ossifies, and there are changes in the layer of skin over it, called the epidermis. which becomes keratinized to generate a hard surface. The middle of the growing horn has a hollow base much like the sinuses we have on our faces, so that, other than at its tip, the horn has a spongy hollow, structure (D). “Keratinization of the epidermis” this paper notes, “continues throughout the animal’s life and, depending on the species, the horns can take various lengths, sizes, and shapes.” There was some dispute as to whether a cow’s horn grows from the base of from the tip. But in their 1983 review paper The Interrelationships of Higher Ruminant Families with Special Emphasis on the Members of the Cervoidea, Janis and Scott conclude that “in fact, neither the core nor the sheath grow from the base.The bony core grows both from the tip and by appositional growth over the surface and the sheath is continually produced over the entire surface of the core.”

We can conclude therefore that the horn of a cow does indeed grow continually, although not annually, like the rings of a tree. Abayye, who died in 337, knew cows. But there is one problem with his explanation. Sheep belong to the same family as cows. It is called the Bovidae and includes cattle, sheep, and antelope, as you can see below in the diagram from a group of Israeli researchers. And sheep grow their horns just like cattle, which means that they also grow them “גִּילְדֵי גִּילְדֵי" or in layers. Which would make them just as forbidden as cow’s horns. Just don’t tell that to the person who blows shofar.

From Dekelet al. Dispersal of an ancient retroposon in the TP53promoter of Bovidae: phylogeny, novel mechanisms, and potential implications for cow milk persistency. BMC Genomics (2015) 16:53.