The Vilna Gaon, (lit. The Genius of Vilna) lived from 1720-1797, and today, the 19th of Tishrei, is the Hebrew anniversary of his death. He was one of the leading talmudic and halakhic authorities of his time. His works are widely studied to this day, and his legal opinions are often cited. Today’s question is: did the Vilna Gaon stay awake for several consecutive days one Sukkot? Here is the background:

The Vilna Gaon.

In January 1788 the Vilna Gaon was involved in the kidnapping of a young Jewish man who had converted to Christianity. For his role in the kidnapping Rabbi Eliyahu (the given name of the Gaon) was arrested and held for over a month. The case was later tried, and on September 15, 1789 (sic) the Gaon of Vilna, together with others involved in the kidnapping, was sentenced to twelve weeks in jail. Although it is unclear how long he was imprisoned, he was there over Sukkot, and the Lithuanian authorities were hardly in the practice of providing imprisoned Jews with a sukkah. But since one is not permitted to sleep outside of the sukkah, what was the Gaon to do? Simple. He’d stay awake, and by doing so he would not transgress the prohibition of sleeping outside the sukkah. Here’s how the episode is described in the work Tosefet Ma’aseh Rav published in 1892.

Our Leader, teacher and Rabbi may he rest in peace, when he was imprisoned on Sukkot, tried with all his strength, and walked from one place to another, and held his eyelids open, and made an extraordinary effort not to sleep outside the sukkah – not even a brief nap – until the authorities released him to a sukkah.

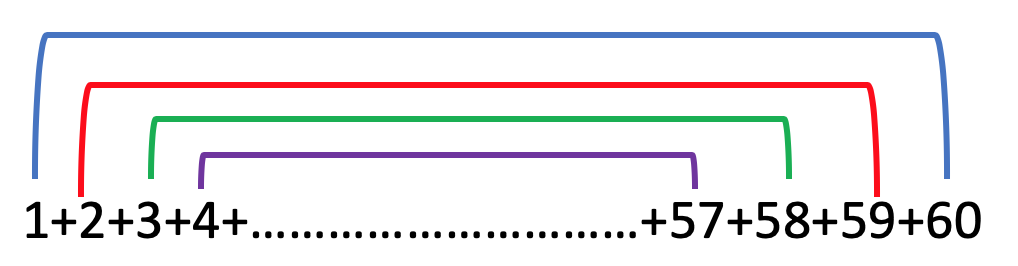

We don’t know for how many nights the sixty-nine year-old Rabbi Eliyahu stayed awake, but is such a claim even plausible? As it turns out, it is.

The World Record for Staying Awake

The world record for staying awake is an amazing eleven days. Eleven days – that’s 264 hours (and 24 minutes to be precise) without sleep. It was set in 1965 by Randy Gardner, who was then seventeen years old. Gardner seems to have suffered little if any harm by his marathon period of sleep deprivation. But don’t try and beat the record. The Guinness Book of Records no longer has an entry for staying awake – because it is considered too dangerous an ordeal to undertake. (You can hear a review of sleep deprivation stunts in general and a wonderful interview with Gardner himself here.)

The Health Risks of Sleep Deprivation

What are the health risks of prolonged sleep deprivation? A 1970 study of four volunteers who stayed awake for 205 hours (that’s eight and a half days!) noted some differences in how the subjects slept once they were allowed to do so, but follow-up testing of the group conducted 6-9 months after the sleep deprivation showed that their sleep patterns were similar to the pre-deprivation recordings.

Although Randy Gardner and these four volunteers seem to have suffered no long-term health consequences of staying awake for over a week, scientists have long noted that sleep deprivation is rather bad for the body. Or to be more precise, the bodies of unfortunate laboratory rats who are not allowed to sleep. In these animals, prolonged sleep deprivation causes the immune system to malfunction. This results in infection and eventual lethal septicemia. The physiologist who kept these rats awake noted that there are “far-reaching physical implications resulting from alterations in immune status [which] may explain why sleep deprivation effects are risk factors for disease and yet are not well defined or specifically localized.” In other words, sleep deprivation makes rats really sick, but we don’t know how, or why…

One possible explanation was suggested in 2013 by a group from the University of Rochester Medical Center. They demonstrated that during sleep, the space between the cells of the brain (the interstitial space) increased by up to 60%, allowing toxic metabolites to be cleared. This raises the question of whether the brain sleeps in order to expel these toxic chemicals, or rather it is the chemicals themselves that drive the brain to switch into a sleep state.

The extracellular (interstitial) space in the cortex of the mouse brain, through which cerebral spinal fluid moves, increases from 14% in the awake animal to 23% in the sleeping animal, an increase that allows the faster clearance of metabolic waste products and toxins. From Suzana Herculano-Houzel. Sleep it out. Science 2013: 342; 316

Not having any sleep is bad for your health - but so too is going without enough sleep. Chronic restriction of sleep to six hours or less per night can produce cognitive performance deficits equivalent to up to two nights of total sleep deprivation. So be sure to get a full night's rest.

Hard, But Not Impossible

The world record set by Randy Gardner has implications for a talmudic decision. In the tractate Shavuot (26b) Rabbi Yochanan ruled that since it was impossible to stay awake for more than three days, any vow to do so is considered to have been a vow made in vain – and punishment follows swiftly. Here is how the ArtScroll Talmud explains this ruling, (based on the explanation of the Ran).

Since it is impossible for a person to go without sleep for three days, the man has uttered a vain oath. Hence, he receives lashes for violating the prohibition (Exodus 20:7): לא תשא את שם ה׳ אלוקיך לשוה, You shall not take the Name of Hashem, your God, in vain. And since the oath -being impossible to fulfill -has no validity, he is not bound by it at all and may sleep immediately.

Maimonides codified this law and also assumed that it is impossible to stay awake for three consecutive days.

רמב"ם הלכות שבועות פרק ה הלכה כ

נשבע שלא יישן שלשת ימים, או שלא יאכל כלום שבעת ימים וכיוצא בזה שהיא שבועת שוא, אין אומרין יעור זה עד שיצטער ויצום עד שיצטער ולא יהיה בו כח לסבול ואח"כ יאכל או יישן אלא מלקין אותו מיד משום שבועת שוא ויישן ויאכל בכל עת שירצה

If a person swore that he would not sleep for three days, or would not eat anything for seven days, or something similar, this is considered a false oath. We do not tell the person to stay awake until it is impossible to do so, or fast for as long as possible until the discomfort is too great to bear, and then allow him to eat or sleep. Rather he is punished with lashes immediately for making a false oath, and is then allowed to sleep or eat as much as he wants…

Based on Randy Gardner’s feat, Rabbi Yochanan was incorrect when he ruled that it was impossible to stay awake for three days. It's certainly not impossible, but that hardly means it's a good idea to try.

It also means that the story of the Gaon of Vilna’s sleepless nights in that cold prison might indeed have occurred. Still it is best not to disrupt your usual sleep patterns. Perhaps that is why Rabbi Chaninah ben Chachina'i in Masechet Avot (3:4) taught that one who stays awake at night "will forfeit with his life." Now that's a warning to heed.

רבי חנינא בן חכינאי אומר הנעור בלילה ... הרי זה מתחייב בנפשו

HAPPY SUKKOT FROM TALMUDOLOGY

“Sleep deprivation reduces learning, impairs performance in cognitive tests, prolongs reaction time, and is a common cause of seizures. In the most extreme case, continuous sleep deprivation kills rodents and flies within a period of days to weeks. In humans, fatal familial or sporadic insomnia is a progressively worsening state of sleeplessness that leads to dementia and death within months or years. ”