Toilet paper has been in short supply recently. But it was non-existent in talmudic times. People used stones instead. Today’s page of Talmud gets into the details of personal hygiene, and discusses how the stones used to clean oneself after defecation may be prepared and used on Shabbat:

שבת פא,א

זוּנִין עַל לְבֵי מִדְרְשָׁא, אֲמַר לְהוּ: רַבּוֹתַי, אֲבָנִים שֶׁל בֵּית הַכִּסֵּא שִׁיעוּרָן בְּכַמָּה? אָמְרוּ לוֹ: כְּזַיִת כֶּאֱגוֹז וּכְבֵיצָה. אֲמַר לְהוּ: וְכִי טוּרְטָנֵי יַכְנִיס? נִמְנוּ וְגָמְרוּ מְלֹא הַיָּד. תַּנְיָא, רַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר: כְּזַיִת כֶּאֱגוֹז וּכְבֵיצָה. רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בְּרַבִּי יוֹסֵי אוֹמֵר מִשּׁוּם אָבִיו: מְלֹא הַיָּד

Examples of terracotta pessoi found in Roman latrines dating from the 2nd century AD. The one on the left comes from Utica (Sicily). The one the right was found in Crete. From Charlier, P. Brun L. Prêtre C. Huynh-Charler I. Toilet Hygiene in the Classical era. British Medical Journal. 2012; 345; e8287.

The Gemara relates: Zunin entered the study hall and said to the Sages: My teachers, with regard to stones that may be moved on Shabbat for wiping in the bathroom, how much is their measure? They said to him: Stones of only three sizes may be moved for that purpose: An olive-bulk, a nut-bulk, and an egg-bulk. He said to them: And will he take scales [turtani] into the bathroom to weigh each stone? They were counted and the Sages concluded that one need not measure the stones. He simply takes a handful of stones. It was taught in a baraita: Rabbi Yosei says the measure of bathroom stones is an olive-bulk, a nut-bulk, and an egg-bulk. Rabbi Shimon, son of Rabbi Yosei, says in the name of his father: One need not measure the stones. He simply takes a handful of stones.

Roman Toilet HygiEne

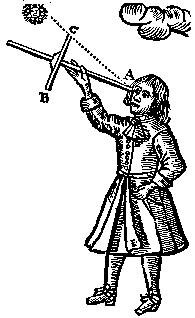

Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Drinking Cup (kylix) c. 500 BCE. From Orvieto Greece. A gift of Edward Perry Warren to MFA; accessioned 1910. Accession # RES.08.31b

In a helpful paper titled Toilet hygiene in the classical era, the authors explain that in the Roman world there was no toilet paper. After defecation, the Roman rear end would be cleaned with a natural sponge attached to a stick called a tersorium. This sponge was then rinsed off in water or vinegar and thoughtfully left for the next person to use. They also used small stones or ceramic fragments called pessoi in place of a sponge, much like those described in today’s page of Talmud. These pessoi have been uncovered in ancient latrines all around the Mediterranean.

The next time you have a chance to visit the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, have a look at their Greek drinking cup or kylix dated around 500 BCE (accession number RES.08.31b.) It demonstrates (as if you needed an explanation) how these pessoi were used. A man is shown semi-squatting with his clothing raised. While he maintains his balance with a cane in his right hand he is clearly wiping his buttocks using a pessos with his left hand. So now you know.

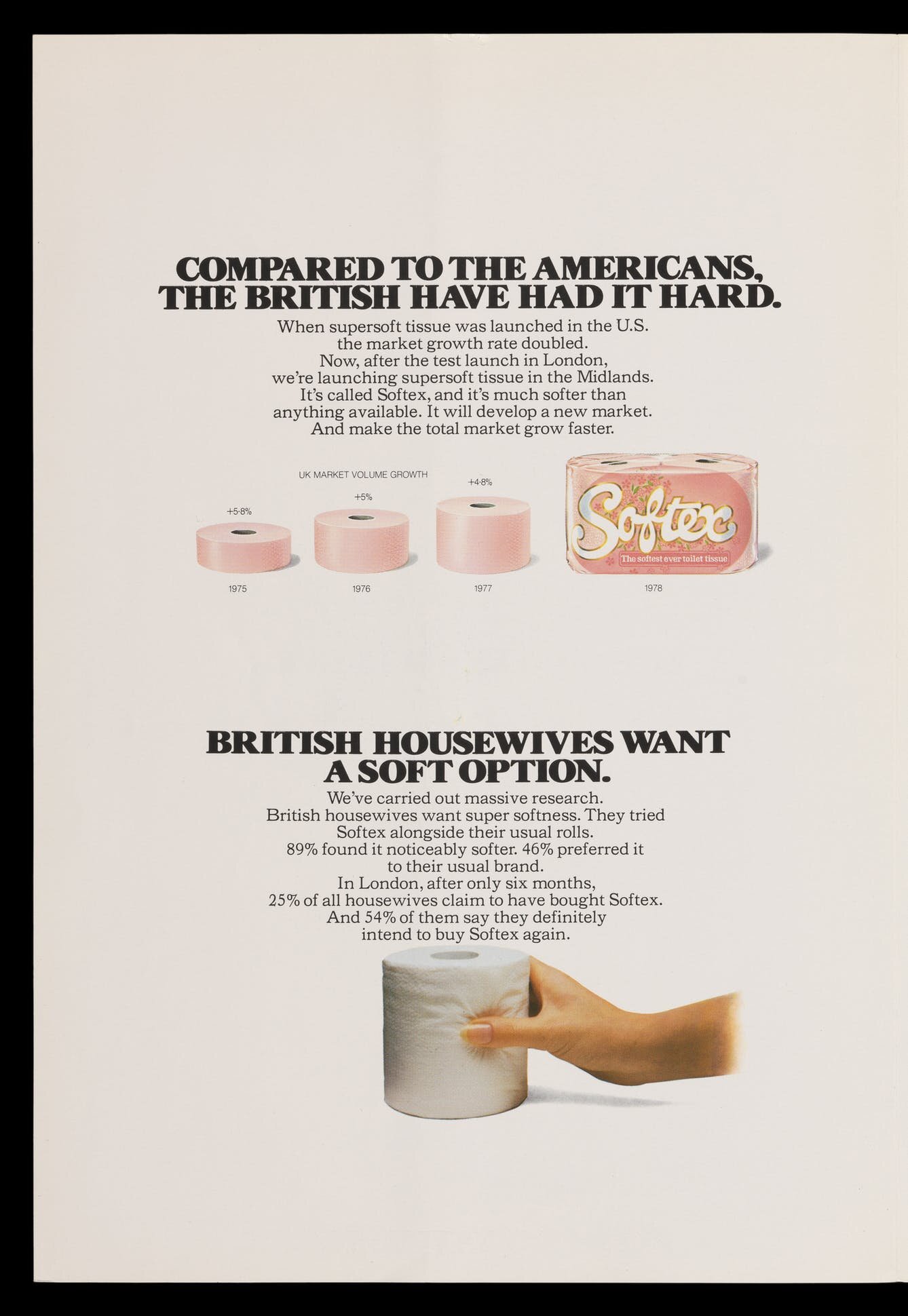

Early Toilet Paper

I remember waxed toilet paper, rather like baking paper (yes, it was once a thing) from my grandparents homes in north London in the 1960s and 70s. Rather inexplicably, the British once liked their paper to be hard and impervious to absorbing anything, and had to be persuaded to try a softer approach.

Toilet paper was used in China as early as the sixth century CE. In fact the scholar Ten Chih-Thui (531-91 CE) wrote that “paper on which there are quotations or commentaries from Five Classics or the names of sages, I dare not use for toilet purposes.” All this was a bit much for an Arab traveller through China in 851. He was horrified at the practice of using toilet paper: “They are not careful about cleanliness, and they do not wash themselves with water when they have done their necessities; but they only wipe themselves with paper.” One can only wonder what the traveller would have thought of the English and their waxed shiny toilet paper.

Toilet Paper and Human Dignity

Later in today’s page of Talmud, Rav Chisdah was asked if it would be permitted to carry the pessoi up to a rooftop latrine on Shabbat. The concern here is that this would involve additional exertion, which is forbidden. Rav Chisdah ruled that it was certainly permissible, because “human dignity is so important that it suspends a prohibition of the Torah” (גָּדוֹל כְּבוֹד הַבְּרִיּוֹת שֶׁדּוֹחֶה אֶת ״לֹא תַעֲשֶׂה״ שֶׁבַּתּוֹרָה).

This lofty principal has many disparate applications; it has been cited in modern responsa literature as the driving force behind allowing the deaf to wear hearing aids on Shabbat, or allowing women to be called to read from the Torah. But from today’s page of Talmud we are reminded that, for the rabbis of the Talmud, the principal of human dignity operates in our most private and intimate spaces.