Getty Images

נדה ח, ב

דאיכא דילדה לט' ואיכא דילדה לשבעה

Some women give birth after nine months, and some after seven months…

Hang on. What about women who give birth after eight months? Why aren’t they on this brief list? The answer is that in talmudic times, a baby born after eight months of gestation was thought to be unable to survive.

A Baby at the Window

Here is an example. In a passage from the tractate Bava Basra we read a list of objects which, if placed in an opening between rooms, blocks the tumah (ritual impurity) from passing from one room into the next. Among that list is a baby born after only eight months of gestation:

בבא בתרא כ, א

עשבין שתלשן והניחן בחלון או שעלו מאליהן בחלונות ומטלוניות שאין בהן שלש על שלש והאבר והבשר המדולדלין בבהמה ובחיה ועוף ששכן בחלון ועובד כוכבים שישב בחלון ובן שמנה המונח בחלון והמלח וכלי חרס וספר תורה כולם ממעטין בחלון

Grass that was plucked and placed in an opening, or grass that grew by itself in an opening; scraps of fabric that are smaller than three by three fingerbreadths; a partially severed limb or a piece of flesh hanging from a domestic or a wild animal; a bird resting in an opening; an idol worshipper sitting in an opening; a baby born after only eight months of gestation lying in an opening; salt, earthenware vessels and a Torah scroll -all of these reduce the size of the opening and so prevent the tumah from passing through it.

The Talmud then questions this ruling about the premature child lying on a window between two rooms, one if which contains a source of tumah. Won't the mother of the baby carry the child away? How then can we suggest it will be a barrier to the tumah? The Talmud, as always, has a solution: the case is regarding a child born prematurely on Shabbat. Such a child is mukzteh, that is, it is in a category of objects that must not be moved on Shabbat:

דתניא בן שמנה הרי הוא כאבן ואסור לטלטלו בשבת

For it was taught in a Braisa. A baby born at eight months of gestation is treated like a stone [on Shabbat, because it is muktzeh.]

The premature baby is given the status of a stone because it was not considered to be viable, and as a non-viable human being it does not contract ritual impurity. So that's why the premature baby is listed along with grass, idol worshippers, and the severed limbs of cattle as preventing the transmission of tumah. Got it?

When we studied Yevamot we came across another case which pivoted on the viability of babies born at seven vs. eight months of gestation. The question there was about proving the paternity of a child, and the discussion hinges on the belief that while a child born after seven months of gestation would be viable, a child born at eight months gestation would not be so. Rashi noted the following: בר תמניא לא חיי - "an eight month fetus cannot survive." And so now we can ask, where on earth does this notion come from?

“it is the women who make the judgments and ... insist that the eighth-month babies do not survive, but the others do.”

Seven vs Eight Months of gestation in antiquity

Homer's Iliad, written around the 8th century BCE, records that a seven month fetus could survive. But it is not until Hippocrates (c. 460-370 BCE, or some 500 years before Shmuel), that we find a record of the belief that a fetus of eight months' gestation cannot survive, while a seventh month fetus (and certainly one of nine months gestation) can. His Peri Eptamenou (On the Seventh Month Embryo) and Peri Oktamenou (On the Eight-Month Embryo) date from the end of the fifth century BCE, but this belief is viewed with skepticism by Aristotle.

In Egypt, and in some other places where the women are fruitful and are wont to bear and bring forth many children without difficulty, and where the children when born are capable of living even if they be born subject to deformity, in these places the eight-months' children live and are brought up, but in Greece it is only a few of them that survive while most perish. And this being the general experience, when such a child does happen to survive the mother is apt to think that it was not an eight months' child after all, but that she had conceived at an earlier period without being aware of it.

The belief that an eight month fetus cannot survive has a halakhic ramification: Maimonides ruled that if a boy was born prematurely in the eighth month of his gestation and the day of his circumcision (eight days after his birth) fell out on Shabbat, the circumcision - which otherwise would indeed occur on Shabbat, is postponed until Sunday, the ninth day after his birth.

רמב׳ם הל' מילה יד, א

מי שנולד בחדש השמיני לעבורו קודם שתגמר ברייתו שהוא כנפל מפני שאינו חי... אין דוחין השבת אלא נימולין באחד בשבת שהוא יום תשיעי שלהן

A child born after eight months of gestation before being fully formed is treated as a stillbirth because it will not live...and we do not set aside the laws of Shabbat [to circumcise him] but he is circumcised on Sunday, which is the ninth day of his life.

This belief persisted well into the early modern era. Here is a state–of–the–art medical text published in 1636 by John Sadler. Read what he has to say on the reasons that an eight month fetus cannot survive (and note the name of the publisher at the bottom of the title page-surely somewhat of a rarity then):

Saturn predominates in the eighth month of pregnancy, and since that planet is "cold and dry"," it destroys the nature of the childe". That, or some odd yearning of the child to be born in the seventh but not the eight month (according to Hippocrates) is the reason that a child born at seven and nine months' gestation may survive, but not one born at after only eight months.

Evidence from Modern Medicine

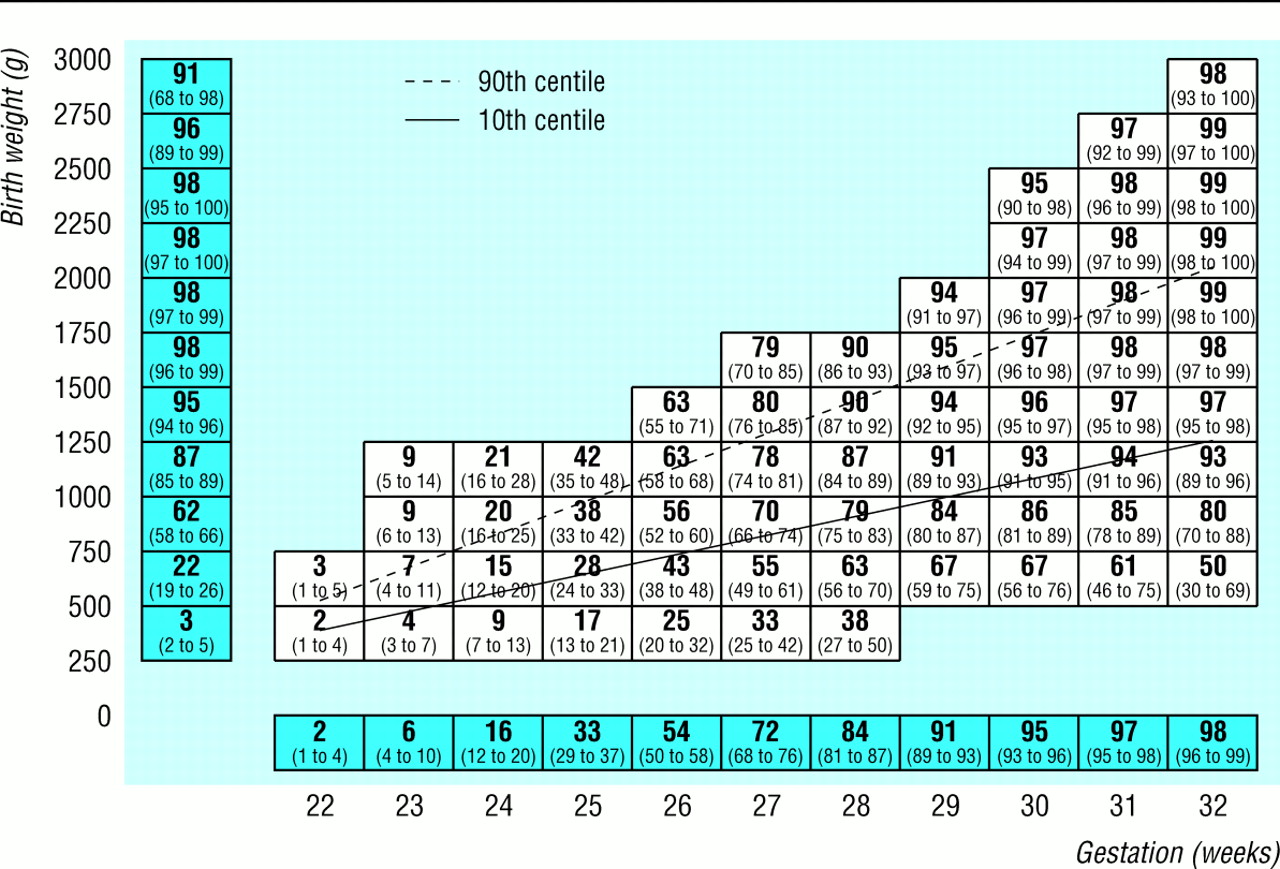

Today we know that gestational length is of course critical, and that, all things being equal, the closer the gestational length is to full term, the greater the likelihood of survival. We can state with great certainty, that an infant born at 32 weeks or later (that's about eight months) is in fact more likely to survive than one born at 28 weeks (a seven month gestation.) In fact, a seven month fetus has a survival rate of 38-90% (depending on its birthweight), while an eight month fetus has a survival rate of 50-98%. Here is the data, taken from a British study.

Draper, ES, Manktelow B, Field DJ, James D. Prediction of survival for preterm births by weight and gestational age: retrospective population based study British Medical Journal 1999; 319:1093.

More recently, a study from the Technion in Haifa showed that even the last six weeks of pregnancy play a critical role in the development of the fetus. This study found a threefold increase in the infant death rate in those born between 34 and 37 weeks when compared full term babies.

You can read more on the history of the eight month fetus in a 1988 paper by Rosemary Reiss and Avner Ash. From what we have reviewed, the talmudic belief that a seven month fetus can survive but an eight month fetus cannot is one that was widely shared in the ancient world, and even in the early modern era. But all the evidence we have today firmly demonstrates that it is simply not true.

[Mostly a repost from here.]