כריתות ז,ב

אלו שאין מביאות… יוצא דופן. ר' שמעון מחייב ביוצא דופן

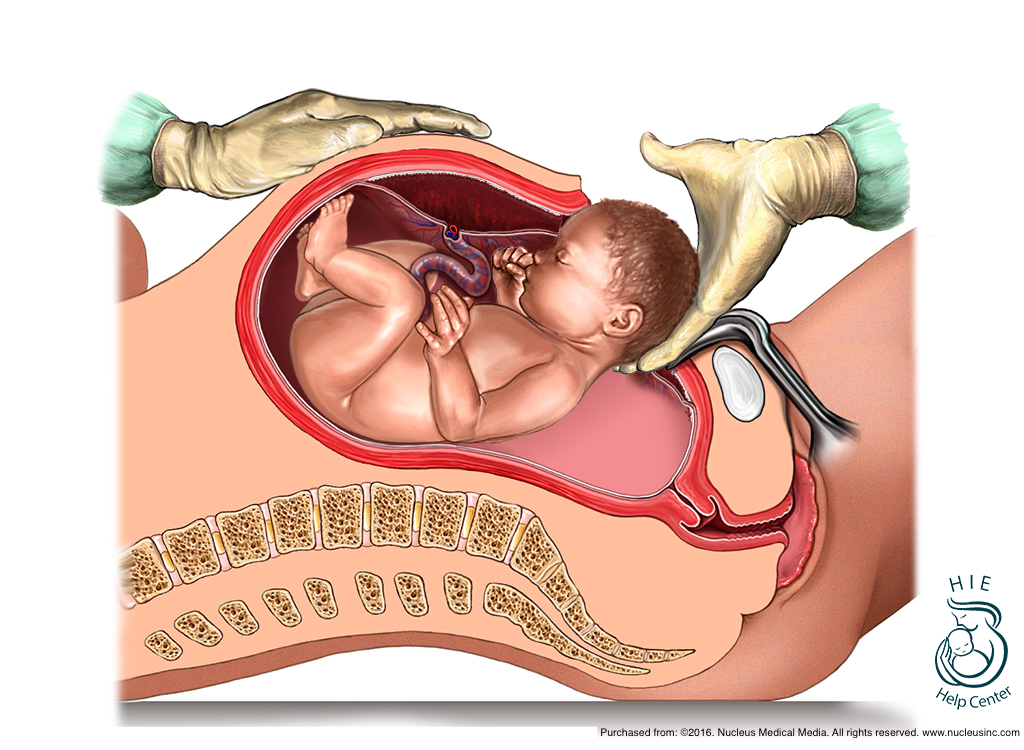

These women do not bring a sin offering… a woman who gives birth by caesarean section. Rabbi Shimon deems a woman liable to bring a sin offering in the case where she gives birth by caesarean section.

Cesarean section. From here.

In a list of the women who need to bring a sacrifice after childbirth or a miscarriage, the Mishnah exludes a woman who underwent a cesarean section. She is not required to bring a sacrifice, although Rabbi Shimon disputes this ruling and opines that a sacrifice is indeed required. This is all very well, but let’s stop for a moment and think about this. The Mishnah was edited around 200 CE; there were neither antibiotics nor anesthetics (at least in any modern sense) and there was no germ theory of disease. Postpartum maternal deaths following natural childbirth common enough, but the rates of a woman surviving a cearean section must have been extremely low. Yet here is the Mishnah teaching that a woman who recovers from this operation is exempt from bringing a sacrifice, which implies that surviving a cearean section was an event so common that it required its own legal ruling.

dying by cesarean section

“Death borders upon our birth

And our cradle stands in the grave

”

Precisely because it was so unlikely for a woman to survive a cesarean section, historians believe that despite his name, Julius Caesar could not have been born as a result of this procedure. “Caesar’s mother Aurelia survived childbirth and outlived her son to bury him 55 years later” wrote one reviewer of a history of cesarean section. “The fact that she lived and gave birth successfully rules out the possibility that Caesar was born in this way.” In fact the first recorded case of a mother and baby both surviving a cesarean section was only in 1500 (that’s 1,300 years after the Mishnah). It occurred in Switzerland,

where Jacob Nufer, a pig gelder, reportedly performed the operation on his wife after a prolonged labour. She spent several days in labour and had assistance from 13 midwives but was still unable to deliver her baby. Her husband received permission from the religious authorities to perform a caesarean section. Miraculously, the mother lived and subsequently gave birth to five other children by vaginal deliveries including twins. The baby lived to the age of 77 years.

But even this story may not be accurate, since it was only reported some eighty years after the event. It was only with the introduction of chloroform as an anesthetic and hand-washing as means of reducing maternal mortality (both around 1847) that the cesarean became a viable means of saving the life of either mother or infant. So why did the Mishnah bother to record the dispute as to whether a woman who survived a c-section brings a sacrifice?

“Hitherto it has commonly been concluded or assumed that there is no sound evidence for caesarean section with maternal survival before 500 A.D. If, however, the rabbinical reports are accepted as implying familiarity with the mother’s recovery from the operation, the date for the earliest practice of caesarean section with a successful outcome for both mother and child must be advanced by almost a millennium and a half.”

survival after cesarean section

It turns out that contrary to expectations, during the time of the Mishnah in the second century, “Jews practiced caesarean section not only to rescue an infant from a dead mother, but also to rescue both mother and baby from a prolonged labour. The mother's survival is implicit in written passages which are unambiguous on the matter, serious in purpose, and certainly not the subjects of modern amendment.” At lest that is the claim made by Jeffrey Boss, in a 1961 paper published in the journal Medical History.

Let’s start with an easier case: animals. The Mishnah in Bechorot (2:9) describes a dispute between Rabbi Tarphon and Rabbi Akivah regarding the special status of an animal born by cesarean section, and its sibling, born naturally later on. In his commentary, Maimonides wrote:

יוצא דופן הוא שיקרע כסל הבהמה ויצא הוולד משם ועושים זה כמו כן באשה שתקשה ללדת והגיעה לשערי מות

Through the wall: this means that the animal is cut open and the calf removed. This is also done to a dying woman who is unable to deliver her baby naturally.

Maimonides, - himself a physician of great repute - does not dispute whether an animal could survive a c-section. He just accepts it as fact. Now let’s consider another Mishnah in the same tractate Bechorot (8:2), that deals with the special obligations surrounding a first-born child.

יוֹצֵא דֹפֶן וְהַבָּא אַחֲרָיו, שְׁנֵיהֶם אֵינָן בְּכוֹר לֹא לַנַּחֲלָה וְלֹא לַכֹּהֵן. רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר, הָרִאשׁוֹן לַנַּחֲלָה, וְהַשֵּׁנִי לְחָמֵשׁ סְלָעִים:

A baby extracted by means of a caesarean section and one that follows is not a first-born for inheritance or a first-born to be redeemed from a priest. Rabbi Shimon says: the first is a first-born for inheritance and the second is a first-born as regards [the redemption] with five selas.

Clearly this Mishanha assumes that the mother survived a cesarean and then gave birth to another child. Next, consider the explanations given by the rabbis of the Talmud who comment on our Mishnah on today’s page of Talmud:

מ"ט דר"ש אמר ר"ל אמר קרא (ויקרא יב, ה) ואם נקבה תלד לרבות לידה אחרת מאי היא יוצא דופן ורבנן מ"ט א"ר מני בר פטיש (ויקרא יב, ב) אשה כי תזריע וילדה עד שתלד ממקום שמזרעת

What is the reason of Rabbi Shimon (who obligates a sacrifice?)? Reish Lakish said that the verse states: “But if she bears a girl”(Leviticus 12:5). The term “she bears” is superfluous in the context of the passage, and it serves to include another type of birth, and what is it? This is a birth by caesarean section. And as for the Rabbis, what is their reasoning? Rabbi Mani bar Pattish said that their ruling is derived from the verse: “If a woman conceives [tazria] and gives birth to a male” (Leviticus 12:2). The word tazria literally means to receive seed, indicating that all the halakhot mentioned in that passage do not apply unless she gives birth through the place where she receives seed, not through any other place, such as in the case of a caesarean section.

Boss notes that the rabbis “make no comment on the implied survival of the mother after the operation, neither explaining away the implication of the Mishnah nor treating it as remarkable.”

In another mishnaic discussion about postpartum ritual uncleanliness (Niddah 5:1) the rabbis again argue with Rabbi Shimon about the obligations of a woman who had given birth by c-section.

נידה מ, א

יוֹצֵא דֹפֶן, אֵין יוֹשְׁבִין עָלָיו יְמֵי טֻמְאָה וִימֵי טָהֳרָה, וְאֵין חַיָּבִין עָלָיו קָרְבָּן. רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן אוֹמֵר, הֲרֵי זֶה כְיָלוּד

For a child born from its mother's side, she does not sit the prescribed days of uncleanness nor the days of cleanness, nor does one incur on its account the obligation to bring a sacrifice. Rabbi Shimon says: it is regarded as a regular birth.

Again, there is no discussion as to whether this could have occurred. It is simply taken as fact. In his commentary on this Mishnah, Maimonides wrote:

רבי שמעון אומר שאמרו תלד לרבות יוצא דופן והוא שישוסע חלצי האשה אם תקשה עליה הלידה ויצא העובר משם

Rabbi Shimon said: When the Torah wrote “if she bears” it includes a child that comes from the side of the belly. This means that because the child will not emerge naturally the loins of the woman are cut open and the child is delivered.

“Maimonides does not here demur to her being well enough to make her purificatory offering” wrote Boss. Another famous commentator on the Mishnah, the fifteenth century Italian Rabbi Ovadiah ben Abraham of Bertinoro also makes the case for surviving a c-section:

יוצא דופן. אשה שפתחו [מעיה] ע״י סם והוציאו העובר לחוץ ונתרפאה:

Through the side of the belly: This means a women whose belly was opened by means of a medicine (סם) and the child was delivered and she survived…

Maimonides didn’t believe a woman could survive

But in fact Maimonides did demur. He demurred a lot. Let’s go back to the back to that Mishnah in Bechorot (8:2) that we cited above: “A baby extracted by means of a caesarean section and one that follows neither is a first-born for inheritance or a first-born to be redeemed from a priest.” (וֹצֵא דֹפֶן וְהַבָּא אַחֲרָיו, שְׁנֵיהֶם אֵינָן בְּכוֹר לֹא לַנַּחֲלָה וְלֹא לַכֹּהֵן). Here is Maimonides:

מה שאפשר להיות בזה שתהא האשה מעוברת משני וולדות ונקרע דופנה ויצא א' מהן ואח"כ יצא השני כדרך העולם ומתה אחר שיצא השני אבל מה שאומרים המגידים שהאשה חיה אחר שקורעים דופנה ומתעברת ויולדת איני יודע לו טעם והוא ענין זר מאד ואין הלכה כרבן שמעון

It may happen that a woman is pregnant with twins, one is delivered by cesarean section, and then the other is delivered normally, and the first child dies after the second is born. But what some say, that a woman can live after her side is cut open and then bear a child, is contrary to reason and utterly absurd…

Notwithstanding the opinion of the great Maimonides, Boss reaches this conclusion:

The texts quoted indicate that the Tannaim assumed that a woman could be fit to offer a sacrifice forty or eighty days after undergoing caesarean section, and that she might be delivered of an infant by a subsequent pregnancy. Internal evidence dates the texts to the second century A.D. and indicates that they were discussions of known possibilities and not of fantasies; the evidence of manuscripts shows that the texts must precede the development of the operation in Europe…The mother's survival is implicit in written passages which are unambiguous on the matter, serious in purpose, and certainly not the subjects of modern amendment.

Cesarean Section Today

You can read the Boss paper here, and decide for yourself if the evidence is persuasive. What is certain is that the cesarean section began as a veterinary procedure. It was once an extremely unusual operation only undertaken as a last ditch effort to save a baby from inside the womb of its dead or dying mother. How things have changed; there are now an estimated 30 million cesarean sections performed around the world each year. In the Dominican Republic, almost 60% of all births are by C-section, and overall they are almost five times more frequent in births in the richest versus the poorest countries. As one news report concluded, when it comes to cesarean section, it’s either too little too late, or too much too soon.

“The skill needed for such an operation implies some general tradition of surgery, and surgery was in fact considerably developed in Talmudic times among the Jews. From the Tannaitic period, the material on surgery is indicative but scanty, but among the Amoraim, who taught between 100 and 300 years later...there was considerable anatomical knowledge and surgical skill...”