דברים 30:12

כִּי הַמִּצְוָה הַזֹּאת אֲשֶׁר אָנֹכִי מְצַוְּךָ הַיּוֹם לֹא־נִפְלֵאת הִוא מִמְּךָ וְלֹא רְחֹקָה הִוא׃

לֹא בַשָּׁמַיִם הִוא לֵאמֹר מִי יַעֲלֶה־לָּנוּ הַשָּׁמַיְמָה וְיִקָּחֶהָ לָּנוּ וְיַשְׁמִעֵנוּ אֹתָהּ וְנַעֲשֶׂנָּה׃

Surely, this instruction which I enjoin upon you this day is not too baffling for you, nor is it beyond reach.It is not in the heavens, that you should say, “Who among us can go up to the heavens and get it for us and impart it to us, that we may observe it?”

Rashi, citing the statement of Avdimi bar Chama bar Dosa (Eruvin 55a) comments:

לא בשמים הוא. שֶׁאִלּוּ הָיְתָה בַשָּׁמַיִם, הָיִיתָ צָרִיךְ לַעֲלוֹת אַחֲרֶיהָ לְלָמְדָהּ

IT IS NOT IN HEAVEN — for were it in heaven it would still be your duty to go up after it and to learn it.

However, elsewhere (Bava Metziah 59b) the Talmud is very clear: when it comes to Jewish law, we keep “the heavens” out of it. When Rabbi Eliezar found himself losing a halakhic battle with his colleagues, he arranged for a series of miracles to prove that his ruling was correct. Here is what happened next:

עמד רבי יהושע על רגליו ואמר (דברים ל, יב) לא בשמים היא מאי לא בשמים היא אמר רבי ירמיה שכבר נתנה תורה מהר סיני אין אנו משגיחין בבת קול שכבר כתבת בהר סיני בתורה (שמות כג, ב) אחרי רבים להטות

Rabbi Yehoshua stood on his feet and said: It is written: “It is not in heaven” (Deuteronomy 30:12). The Gemara asks: What is the relevance of the phrase “It is not in heaven” in this context? Rabbi Yirmeya says: Since the Torah was already given at Mount Sinai, we do not regard a Divine Voice, as You already wrote at Mount Sinai, in the Torah: “After a majority to incline” (Exodus 23:2).

Rabbis who Dream and Decide

It is therefore somewhat surprising that this principle was forgotten when some rabbis declared that they had received halakhic rulings in their dreams. Some of them were noted by Ze’ev Zuckerman in his Otzar Pila’ot Hatorah, and this week on Talmudology we will take a closer look at rabbis who claim to have had God tell them directly how to rule.

First, let’s note that after Rabbi Eliezer’s claim of support via miracles, the earliest example of paksening (ruling) via dreams can be found in the writings of Natronai Ben Hilai Hacohen, known as Natronai the Gaon, who lived in Mesopotamia in the late 9th century and headed the Yeshiva in Sura. He was asked whether a person who converts out of Judaism may legally inherit his father’s property. Nope. “כך הראוני מן השמים שמשומד אינו ירוש אביו.” “This is what was taught to me from heaven: an apostate may not inherit his father.”

The Rashba

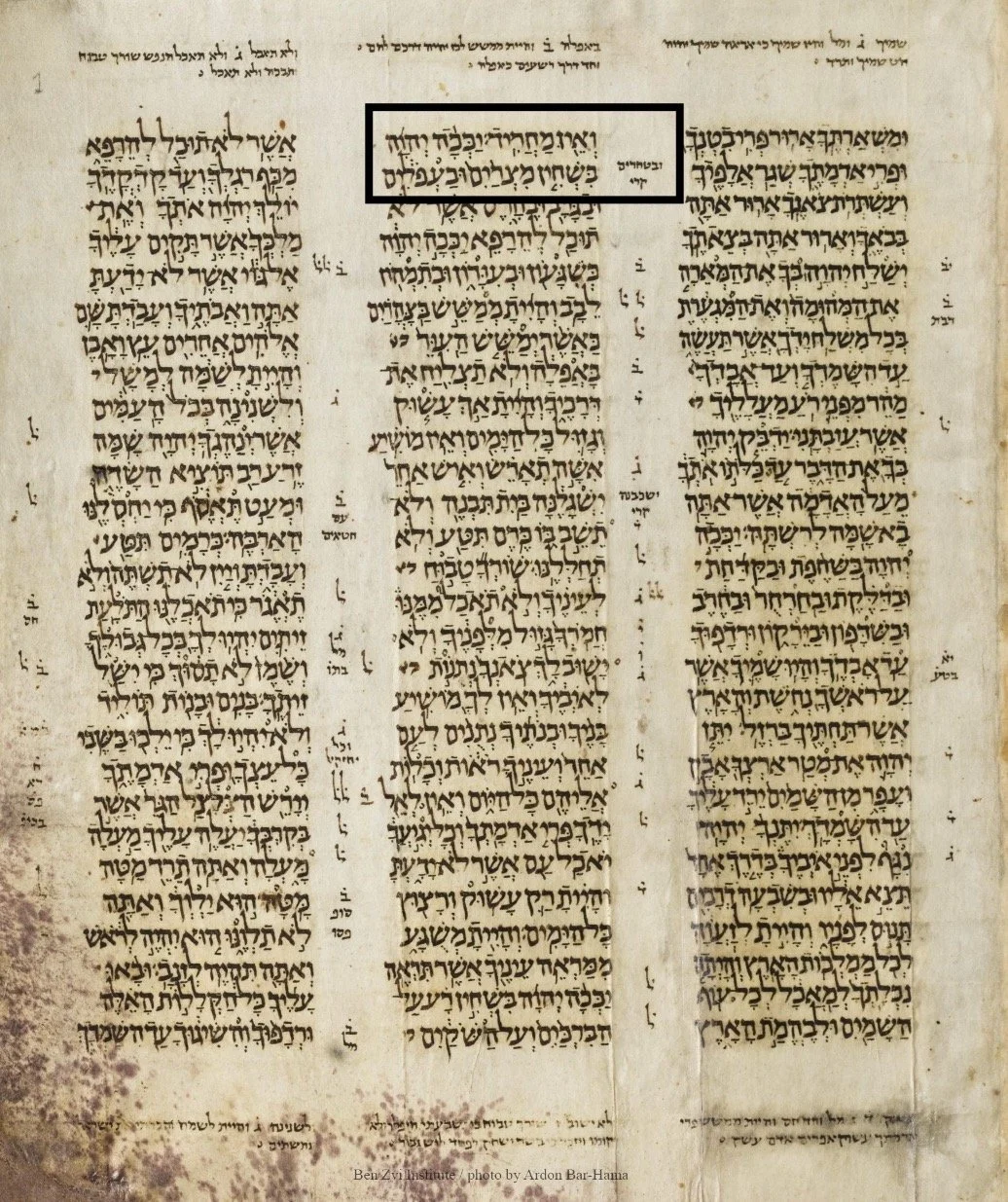

Shlomo ben Avraham ibn Aderet (1235-1310) was a Spanish rabbi who left a great many responsa (actually more than 3,000 according to this source). I counted at least 19 that have the phrase שהראוני מן השמים “as shown to me from heaven” in them. Here is the first responsum in which this phrase appears, shown in the red box.

שו"ת הרשב"א - א בני ברק, תשי"ח - תשי"ט

The Ra’avad

Abraham ben David (best known by his acronym Ra’avad, c.1125-1198) lived in Provence and is famous for his (sometimes quite hostile) commentary on the Mishneh Torah of Maimonides. In the Laws of the Lulav (8:8) Maimonides outlined the blemishes that render a myrtle (hadas) as useless. However, according to Maimonides, “a myrtle branch whose top is cut off is acceptable.” But that wasn’t how the Ra’avad ruled. And he had it on good authority:

הדס שנקטם וכו'. כתב הראב"ד ז"ל כבר הופיע רוח הקודש בבית מדרשנו מכמה שנים והעלינו שהוא פסול כסתם מתני'. ודברי רבי טרפון שאמר אפילו שלשתן קטומים כשר ענין אחר הוא ולא שנקטם ראשו והכל ברור בחבורנו ומקום הניחו לי מן השמים עכ"ל

The Holy Spirit (רוח הקודש) has appeared in our Bet Midrash (study hall) over a number of years and has ruled that such a myrtle is forbidden…

Shut Min Hashamayim - The Responsa From Heaven

The thirteenth century French kabbalist Jacob HaLevi of Marvège (יעקב הלוי ממרויש) took this heaven thing and cranked the volume up to 11. He wrote a series of responsa whose halakhic decisions, he claimed, were revealed to him in his dreams. He called the work, appropriately, “שאלות ותשובות מן השמים” - Questions and Answers From Heaven. In a fascinating article on the work, the late Israel Ta-Shema (1936-2004) wrote that it was cited as early as 1215 (in a book called Hamanhig by Avraham Hayarechi). It was used widely during the middle ages and “many important poskim [religious authorities] relied on it when ruling.”

The Magid Mesharim - The Preacher of RIGHTEOUSNESS

Not to be outdone, no less a personality than Yosef Karo (or Caro, 1488-1575), the author of the authoritative Shulchan Aruch, (Code of Jewish Law) also claimed to have been visited by heavenly creatures who would urge him on to new spiritual heights. He wrote a book about these encounters which he called Maggid Mesharim - The Preacher of Righteousness. Writing in the Jewish Encyclopdia, here is how Louis Ginzberg explained the book:

This book is a kind of diary in which Caro during a period of fifty years noted his discussions with his heavenly mentor, the personified Mishnah. …The discussions treat of various subjects. The maggid enjoins Caro to be modest in the extreme, to say his prayers with the utmost devotion, to be gentle and patient always. Especial stress is laid on asceticism; and Caro is often severely rebuked for taking more than one glass of wine, or for eating meat. Whenever Caro did not follow the severe instructions of his maggid, he suddenly heard its warning voice. His mentor also advised him in family affairs (p. 21b), told him what reputation he enjoyed in heaven, and praised or criticized his decisions in religious questions…

The present form of the "Maggid Mesharim" shows plainly that it was never intended for publication, being merely a collection of stray notes; nor does Caro's son Judah mention the book among his father's works. It is known, on the other hand, that during Caro's lifetime the cabalists believed his maggid to be actually existent …. The "Maggid Mesharim," furthermore, shows a knowledge of Caro's public and private life that no one could have possessed after his death; and the fact that the maggid promises things to its favorite that were never fulfilled—e.g., a martyr's death—proves that it is not the work of a forger, composed for Caro's glorification...

Some Halachik rulings determined by dreams

Is Balbuta Kosher?

Balbuta was some kind of fish that shed its scales as it grew. (Perhaps it was this fish). Rabbi Ephraim of Regensburg (1110-1175) ruled that it was kosher, as had Rashi and his two famous grandsons Rashbam and Rabbenu Tam. According to the account of R. Baruch of Mainz (1150-1221) the night after R. Ephraim made his fishy ruling, he [Ephraim] had a dream

“that he was being presented with a brimming plate of non-kosher crustaceans by an elderly man with a pleasant countenance, white hair, and a flowing white beard. The elderly man bid R. Ephraim to eat from this plate, but Ephraim adamantly (and even angrily) refused, explaining to the man that these were non-kosher sea creatures. The man responded, “These are as permitted (for consumption) as the non-kosher species (sherazim) that you allowed today.” When R. Ephraim awoke, he understood that Elijah the Prophet had appeared to him, and he refrained away from (eating) those fish from that day on (me-hayom va-hal’ah piresh me-hem)” (From here.)

Lung adhesions and kashrut

R. Isaiah di Trani, known as the Rid (c.1180-c1250) ruled that certain lung adhesions that were found in a slaughtered animal rendered it treif, and as a result its meat could not be eaten. While he recognized that in general one may not be guided by dreams when reaching halakhic decisions (c.f. Sanhedrin 30a “דברי חלומות לא מעלין ולא מורידין”), the Rid also noted that Elijah the prophet had appeared to him in a dream and that Elihah supported the Rid’s position.

תשובות הריד, ירושלים 1975, #112

3. Paying a worker from the foods he collects

The Mishnah (Bava Metziah 118a) rules that a worker who is paid to collect straw and chafe (which is the husk surrounding a seed, and is generally discarded,) may refuse payment in the form of these items, since they are difficult to trade or exchange for other foods. In the Middle Ages the question arose as to whether this ruling is restricted to wheat and chafe mentioned specifically in the Mishnah, or is generalisable to other low quality items a worker is paid to collect.

One of the great medieval talmudists used a dream to decide the issue. Mordechai ben Hillel, known simply as “the Mordechai” (c.1250-1298) was a German posek whose rulings to this day are printed at the back of the standard editions of the Talmud. And here is his one of them:

מרדכי מסכת בבא קמא פרק ארבעה אבותֿ

ולמורי ר' מאיר נראה בחלום דוקא בתבן ובקש אבל במידי דאכילה כגון חטין ושעורין ואמר טול מה שעשית בשכרך שומעין לו, וכן פסק להלכה

My teacher R. Meir saw in a dream that only wheat and chafe can specifically be rejected by the worker. But regarding other edible commodities, such as wheat and barley, the hirer may say to the worker “take your wages from this produce.”

4. Is refraining for pride one of the 613 Mitzvot?

Among the earliest works of Jewish Law is that of Moses ben Jacob of Coucy, a 13th century French tosafist and disciple of Rabbi Yechiel of Paris. In 1247 he completed his Sefer Mitzvot Gadol, and he needed to decide whether the sin of pride (גאוה) was one of the 248 negative commandments found in the Torah. He decided it was, and listed it as “Negative Prohibition #64”:

השמר לך פן תשכח את ה' אלהיך אזהרה שלא יתגאו בני ישראל כשהקדוש ברוך הוא משפיע להם טובה ויאמרו שבריוח שלהם ועמלם הרויחו כל זה ולא יחזיקו טובה להקב"ה מחמת גאונם שעל זה עונה זה המקרא ואומר גם בפ' ואתחנן ובתים טובים מלאים כל טוב אשר (מאת) [לא מלאת] וגומ' ואכלת ושבעת השמר לך פן תשכח וגו' וזה הפי' שפירשתי מפורש בסמוך פן תאכל ושבעת ובתים טובים תבנה וישבת ובקרך וצאנך ירביון וכסף וזהב ירבה לך וגומ' ורם לבבך ושכחת את ה' אלהיך המוציאך מארץ מצרים וגו' ואמרת בלבבך כחי ועוצם ידי עשה לי את החיל הזה וזכרת את ה' אלהיך כי הוא הנותן לך כח לעשות חיל ומכאן (ב) אזהרה שלא יתגאה האדם במה שחננו הבורא הן בממון הן ביופי הן בחכמה אלא יש לו להיות ענו מאד ושפל ברך לפני ה' אלהי' ואנשי' ולהודות לבוראו שחננו זה

Beware lest you forget the Lord your God." [Deuteronomy 4:23] This is a warning for the Israelites not to become arrogant when God blesses them with prosperity. They should not claim that all their success is due to their own efforts and hard work, thereby neglecting to acknowledge God's goodness due to their pride. This is what the verse addresses, as it also says in the portion of Va'etchanan, "Houses filled with all good things that you did not fill..." [Deuteronomy 6:11] and continues, "And you will eat and be satisfied, beware lest you forget the Lord your God." This interpretation is further explained nearby, "Lest you eat and be satisfied, and build good houses and live in them, and your cattle and sheep increase, and you gather silver and gold in abundance, and your heart becomes haughty, and you forget the Lord your God who brought you out of the land of Egypt..." and "You will say in your heart, 'My strength and the power of my hand made me all this wealth,' but you shall remember the Lord your God, for it is He who gives you the strength to make wealth." From here (b), there is a warning not to be arrogant about what God has granted, whether it is wealth, beauty, or wisdom. Rather, one should be very humble and lowly before the Lord, their God, and before people, and give thanks to their Creator for granting them these qualities.

Rather surprisingly, Moses then described how he had arrived this interpretation of the verse (Deut. 4:23) השמר לך פן תשכח - “Beware lest you forget the Lord your God."

וכשהגעתי להשלים ע"כ הלאוין וארא בחלום במראית הלילה הנה שכחת את העיקר השמר לך פן תשכח את ה' והתבוננתי עליו בבקר והנה יסוד גדול הוא ביראת השם הואלתי לחברו בעזרת יהיב חכמתא לחכימין

When I reached the completion of the prohibitions and saw in a dream at night that I had forgotten the principle, "Beware lest you forget the Lord," I considered it in the morning, and behold, it is a great foundation in the fear of the Lord. Therefore, I decided to include it, with the help of the One who grants wisdom to the wise…

Lo Bashamayim In Theory and Practice

There are many more examples I could share but let’s conclude with Ephraim Kanarfogel, University Professor of Jewish History, Literature and Law at Bernard Revel Graduate School of Jewish Studies and at Stern College for Women. He concludes his fascinating paper Dreams as a Determinant of Jewish Law and Practice in Northern Europe During the High Middle Ages (from where some of these examples were taken), with this thought:

In sum, the (surprisingly) positive or receptive attitude that a number of Tosafists expressed with respect to the potential impact of dreams on the halakhic process, as well as the differences between them about how such dreams should be evaluated and classified, had much in common with the surrounding host culture, even as the Tosafist attitudes were clearly a function of their own rabbinical and mystical sensibilities. As leading students and teachers of talmudic law, the Tosafists were surely cognizant of the principle, lo ba-shamayim hi, “it is not in heaven.” As religious authorities of their age, however, they were more than willing to entertain the possibility that heavenly, dream-like contra-texts could nonetheless contribute to the halakhic enterprise, and to Jewish life and practice more broadly.

Shabbat Shalom and sweet dreams (חלומות פז) from Talmudology

עד הניצחון

Want even more Talmudology on dreams? Click here.