Here are two posts, one for today’s daf, and one for tomorrow’s. Enjoy, and Shabbat Shalom from Talmudology

אַחֵינוּ כָּל בֵּית יִשְׂרָאֵל

הַנְּתוּנִים בַּצָּרָה וּבַשִּׁבְיָה

הָעוֹמְדִים בֵּין בַּיָּם וּבֵין בַּיַּבָּשָׁה

הַמָּקוֹם יְרַחֵם עֲלֵיהֶם

וְיוֹצִיאֵם מִצָּרָה לִרְוָחָה

וּמֵאֲפֵלָה לְאוֹרָה

וּמִשִּׁעְבּוּד לִגְאֻלָּה

הָשָׁתָא בַּעֲגָלָא וּבִזְמַן קָרִיב

Bava Basra 24a ~The Chatam Sofer, Rationalism,

and Anatomy That Isn't There

In August 2013 a paper published in the otherwise sleepy Journal of Anatomy caused quite a sensation. Although doctors have been dissecting the human body for centuries, it seems that they missed a bit, and a team from Belgium announced that they had discovered a new knee ligament, which they called the anterolateral ligament. On today’s page of Talmud the rabbis describes the opposite phenomena. In it, the rabbis describe an anatomical part that is really hard to identify, and may not exist at all. It is called the aliyah, which usually refers to an attic or the upper chamber of a house.

PROXIMITY or Majority?

The rabbis are trying to resolve the issue of who owns a dove found between two dove cots. How far could it hop, and what difference might that make with regards the decision?

בבא בתרא כג, ב

ניפול הנמצא בתוך חמשים אמה הרי הוא של בעל השובך חוץ מחמשים אמה הרי הוא של מוצאו נמצא בין שני שובכות קרוב לזה שלו קרוב לזה שלו מחצה על מחצה שניהם יחלוקו

With regard to a dove chick [nippul] that was found within fifty cubits of a dovecote, it belongs to the owner of the dovecote.If it was found beyond fifty cubits from a dovecote, it belongs to its finder.In a case where it was found between two dovecotes, if it was close to this one, it belongs to the owner of this dovecote; if it was close to that one, it belongs to the owner of that dovecote. If it was half and half, [i.e., equidistant from the two dovecotes,] the two owners divide the value of the chick.

Fair enough. But Abbaye, the great fourth century Babylonian sage had a different take. Perhaps we should not be concerned with proximity, but instead be concerned with who owns the majority of the doves in the area. And brings a proof that will surprise you.

אמר אביי אף אנן נמי תנינא דם שנמצא בפרוזדור ספיקו טמא שחזקתו מן המקור ואע"ג דאיכא עלייה דמקרבא

Abaye said: We learn in a Mishnah (Niddah 17b) as well that one follows the majority rather than proximity: With regard to blood that is found in the corridor [baperozdor],i.e., the cervical canal, and it is uncertain whether or not it is menstrual blood, it is ritually impure as menstrual blood, as there is a presumption that it came from the uterus, which is the source of menstrual blood. [And this is the halakha even though there is an upper chamber, which empties into the canal, which is closer.]

Here is that Mishnah in full:

נדה יז, ב

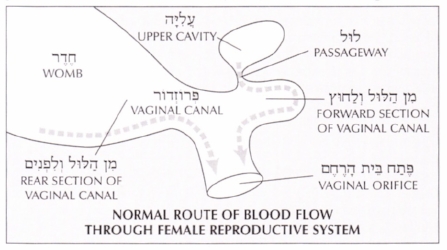

משל משלו חכמים באשה החדר והפרוזדור והעלייה דם החדר טמא דם העלייה טהור נמצא בפרוזדור ספקו טמא לפי שחזקתו מן המקור

The Sages had a parable with regard to the structure of the sexual organs of a woman [based on the structure of a house]: The inner room represents the uterus, and the corridor [perozdor] leading to the inner room represents the vaginal canal, and the upper story represents the bladder.

Blood from the inner room is ritually impure. Blood from the upper story is ritually pure. If blood was found in the corridor, there is uncertainty whether it came from the uterus and is impure, or from the bladder and is pure. Despite its state of uncertainty ,it is deemed definitely impure, due to the fact that its presumptive status is of blood that came from the source ,i.e., the uterus, and not from the bladder.

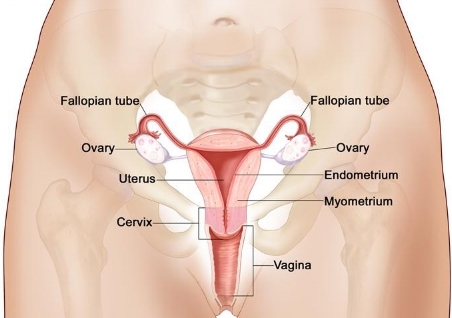

What anatomy is being discussed here? In particular, what is the aliyah, the “attic” of female genital anatomy? It turns out to be complicated.

the Aliyah surrounds the ovaries

From the Mishanh in Niddah, it is clear that the aliyah sometimes bleeds, and that this blood becomes visible when it passes into the vagina. Maimonides identifies the aliyah with the space that contains the ovaries and the fallopian tubes. In modern medicine the ovaries and the Fallopian tubes and tissues that support them are called the adenxa. They are further from the vagina that the uterus, and so this identification does not fit in with Abaye's anatomy in which the aliyah is closer to the vagina than is the uterus.

רמב׳ם הל׳ איסורי ביאה ה, ד

ולמעלה מן החדר ומן הפרוזדוד, בין חדר לפרוזדוד, והוא המקום שיש בו שתי ביצים של אישה, והשבילים שבהן מתבשלת שכבת זרע שלה--מקום זה הוא הנקרא עלייה. וכמו נקב פתוח מן העלייה לגג הפרוזדוד, ונקב זה קוראין אותו לול; והאבר נכנס לפנים מן הלול, בשעת גמר ביאה

Above the uterus and the vagina, between the uterus and the vagina, is the place in which the two ovaries are found, and the tubes along which the sperm from intercourse matures, this place is called the aliyah. (Maimonides, Mishneh Torah Issurie Bi'ah 5:4)

As we said, the problem is that the space which contains the ovaries is inside the abdomen, and this space does not connect with the vagina. It connects via the Fallopian tubes with the uterus. Although Maimonides does not identify the aliyah as the ovaries themselves, some have done so. But the problem with this is that the ovaries don't bleed unless they develop a large cyst which then ruptures. But even in this case they bleed into the abdomen, or into the uterus, again via the Fallopian tubes, and not directly into the vagina.

Menachem ben Shalom (1249-1306) known as the Meiri, wrote an important commentary on the Talmud call Bet Habechirah - בית הבחירה and in it he too identifies the aliyah as the space between the uterus and the vagina in which the ovaries are found. He notes that in this space there are many blood vessels which may rupture and bleed directly into the vagina (עורקים שמתבקעים לפעמים), but as we have noted this is not biologically correct. Any bleeding from the adnexa is via the Fallopian tubes into the uterus itself, and certainly not directly into the vagina.

The Aliyah is the vagina

In his classic Biblisch-Talmudische Medezin published in 1911, Jacob Preuss identified the aliyah as the vagina. "It can be assumed with reasonable certainty" he wrote "that the cheder refers to the uterus, that the prosdor is the vulva, and that the aliyah is the vagina." However certain he may have been, Preuss is the only one to make this identification, which does not fit in with the text of the Mishanh. So let's try another suggestion.

The Aliyah is the Bladder

Sefer Ha'Arukh, Venice 1552.

Natan ben Yechiel of Rome, who died in 1106, wrote an influential lexicon of talmudic terms called the Sefer Ha'Arukh (ספר הערוך) which was first published around 1470. In that work the aliyah is identified as the urinary bladder. This identification also cannot be correct, because the bladder does not empty into the vagina, and because it does not lie between the uterus and the vagina but anterior to them. The commentary in the Schottenstein Talmud to Niddah 17b notes that a connection between the urethra and the vagina (known as a urethero-vaginal fistula) might account for bleeding from the bladder into the vagina. This is possible - though it is of course not normal anatomy.

From here.

The AliyaH is a completely new structure

Meir ben Gedaliah of Lublin (d.1616) also considered the location of the aliyah in his modestly titled book Meir Einei Hakhamim - מאיר עיני חכמים - (Enlightening the Eyes of the Sages) first published in Venice in 1618. He locates it between the uterus and the bladder, and provides two helpful schematics. The problem is that there is no such organ. You won't find it if you dissect a cadaver, and you won't find it in any textbook of anatomy (like this one). And as one astute radiologist and reader of Talmudology recently told me, you won't find it on an MRI either. Here is the text.

Maharam Lublin. Meir Einei Hakhamim. Venice 1618. p255b.

This non-existent anatomy is also pictured in the Schottenstein Talmud (Niddah 17b), based on the difficult Mishanah.

From Schottenstein Talmud Niddah 17b. Note that this does NOT correspond to the known female anatomy, but is a schematic based on Rashi's understanding.

The CHatam Sofer on the Aliyah

Moses Schreiber known as Chatam Sofer, (d. 1839) was a leader of Hungarian Jewry and he too weighed in on the issue in his talmudic commentary to Niddah (18a).

What is the "corridor" or the "room" or the "roof" or the "ground" or the "aliyah" ? After some investigation using books and authors experts and books about autopsies it is impossible to deny the facts that do not accord with the statements of Rashi or Tosafot or the diagrams of the Maharam of Lublin...but you will find the correct diagram in the book called Ma'asei Tuviah and in another book called Shvilei Emunah...therefore I have made no effort to explain the words of Rashi or Tosafot for they are incompatible with the facts...

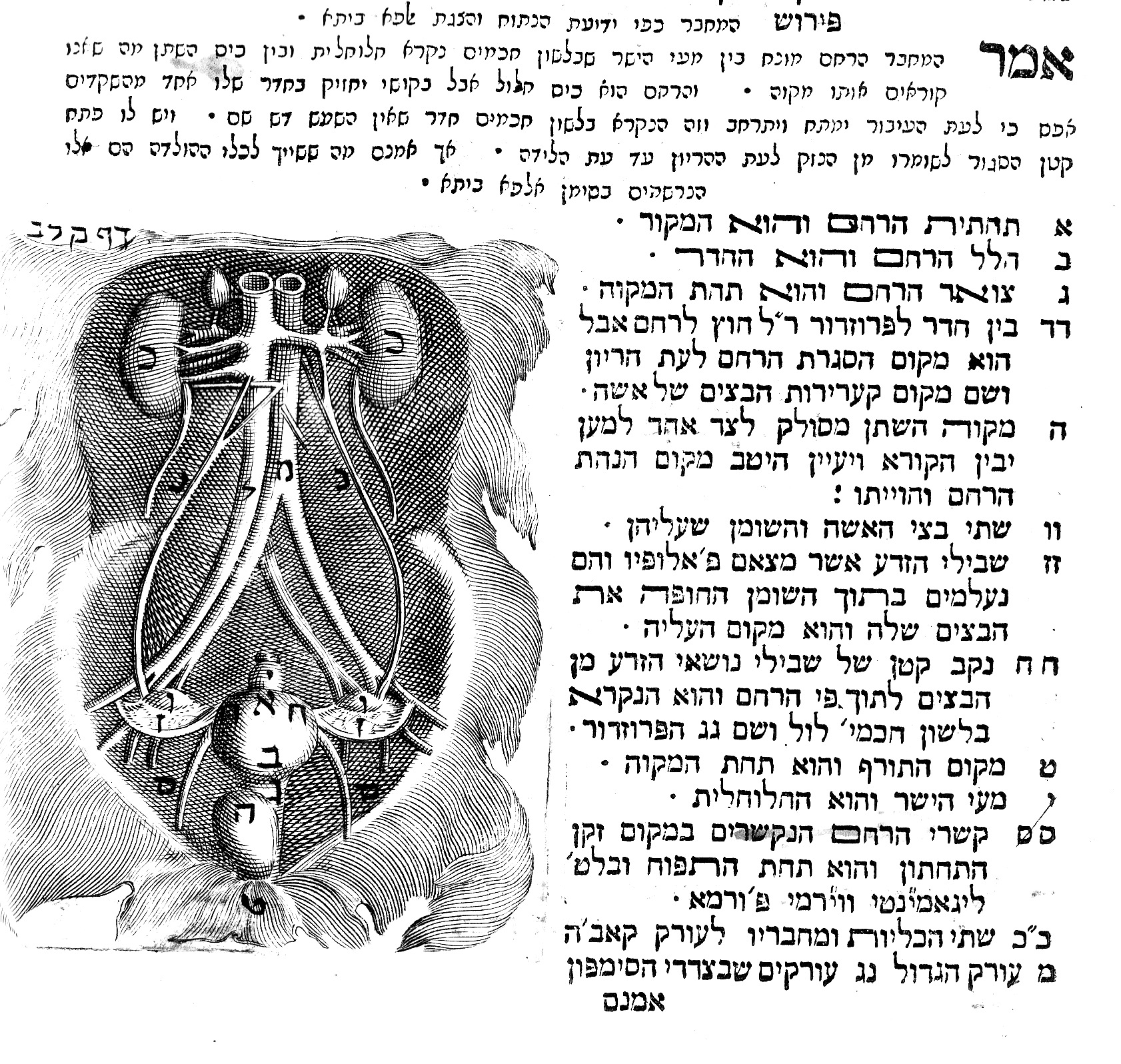

Tuviah HaCohen, the Doctor from Padua

I couldn't find the diagram in any edition of the Shvilei Emunah to which the Chatam Sofer refers, so let's look at the diagram from Ma'asei Tuviah, which I happen to have in my own library.

Detail from Tuviah HaCohen, Ma'aseh Tuviah, Venice 1708. p132b.

A careful reading of the annotation (זז) reveals that Tuviah HaCohen (1652-1729) identifies the aliyah as that area containing the ovaries and the Fallopian tubes. In doing so he followed the opinion of Maimonides that we cited earlier, even though that does not in any way fit in with the understanding of Abaye and his ruling that blood found in the vagina that comes from the aliyah is not impure because it does not come from the uterus. Any gynecologist (or first year medical student completing their anatomy dissections) will tell you that blood from the adnexa (the ovaries and Fallopian tubes) can only get into the vagina via the uterus. But the most interesting part of this diagram is the very first line of text, at the top of the image.

פירוש המחבר כפי ידיעת הנתוח

The author's explanation according to knowledge gained from an autopsy

Anatomical Theatre, Palazzo del Bo, at the University of Padua. It was built in 1594 by the anatomist who helped found modern embryology, Girolamo Fabricius. From here.

Here, perhaps for the first time, anatomical knowledge from an autopsy is being shared in Hebrew. At the medical school in Padua, two bodies (one of each sex) had to be dissected each year, and all the students attended- Tuviah included. As a medical student, Tuviah would have stood in the famous anatomical theater and watched the dissection, perhaps following along in one of the textbooks based on those dissections.

Facts Matter

As the Chatam Sofer noted, facts matter. The illustration in the work of the Maharam of Lublin was an example of trying to get the facts to fit the text of the Mishnah (or more precisely, the explanations of Rashi and Tosafot) but in doing so the Maharam created a fictitious anatomical part.

It is very unlikely that the rabbis of the Talmud witnessed human dissections. In the ancient world two Greeks, Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Ceos (who lived in the first half of the third century BCE) were "the first and last ancient scientists to perform dissections of human cadavers." Facts about human anatomy became clear once human dissection began in the fourteenth century, but as is demonstrated by the Maharam of Lublin, these lessons did not always diffuse into the Jewish community. The Chatam Sofer is often - and rightly - cited as a force for tradition against the challenges from the outside world. But the Hatam Sofer, at least in so far as gynecology was concerned, had no time for a theory when the facts show otherwise. In an age of "alternative facts" the Chatam Sofer is a model of rationalism.

Bava Basra 25b ~

The Sun's Orbit Around the Earth

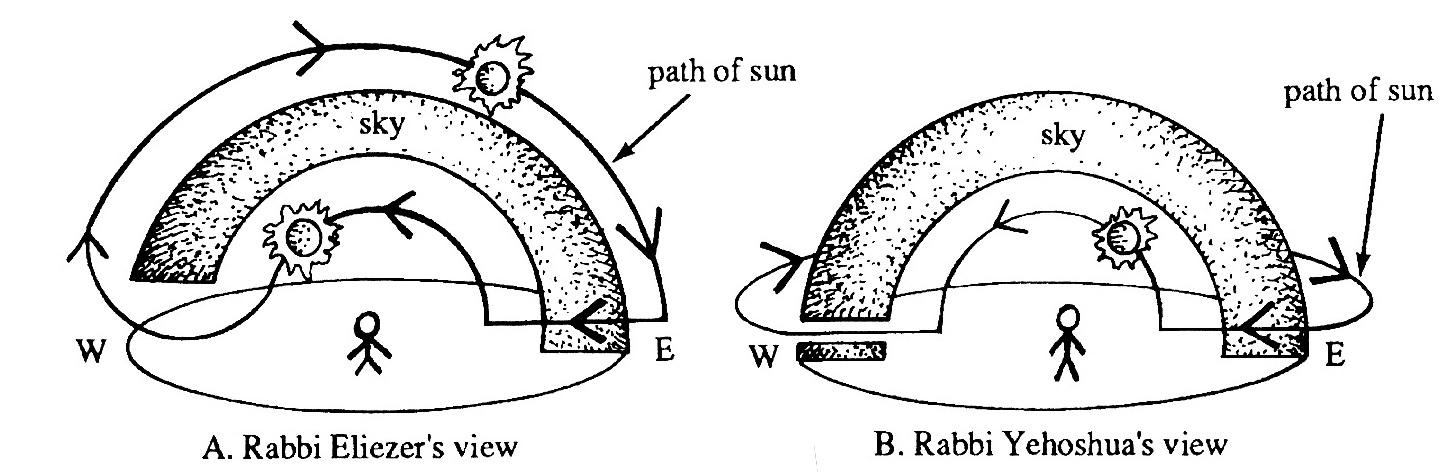

תניא ר"א אומר עולם לאכסדרה הוא דומה ורוח צפונית אינה מסובבת וכיון שהגיעה חמה אצל קרן מערבית צפונית נכפפת ועולה למעלה מן הרקיע ורבי יהושע אומר עולם לקובה הוא דומה ורוח צפונית מסובבת וכיון שחמה מגעת לקרן מערבית צפונית מקפת וחוזרת אחורי כיפה

Rabbi Eliezer taught: The world is similar to a partially enclosed veranda [אכסדרה], [which is enclosed on three sides] and the northern side of the world is not enclosed with a partition like the other directions. When the reaches the northwestern corner it turns around and ascends throughout the night above the rakia [to the east side and does not pass the north side].

Rabbi Yehoshua says: The world is similar to a small tent [קובה], [and the north side is enclosed too,] and when the sun reaches the northwestern corner it orbits and passes behind the dome.

The monthly movement of the Earth, Moon, and Sun, according to Moses Hefez, Melekhet Mahashevet, Venice, 1710. From here

In this passage the path of the Sun is described, and to understand it you need to know this. The rabbis of the Talmud believed that the earth was a flat disc, and that above the sky was an opaque covering called the rakia. During the day the Sun was visible under the rakia, and then at night it zipped back from where it set in the west to where it would rise again in the east by traveling over the rakia. Something like this:

From Judah Landa. Torah and Science. Ktav 1991. p66.

The other place that you will find the path of the Sun discussed in the Talmud is in Pesachim 94b. Here is the text:

חכמי ישראל אומרים ביום חמה מהלכת למטה מן הרקיע ובלילה למעלה מן הרקיע וחכמי אומות העולם אומרים ביום חמה מהלכת למטה מן הרקיע ובלילה למטה מן הקרקע א"ר ונראין דבריהן מדברינו שביום מעינות צוננין ובלילה רותחין

The wise men of Israel say that during the day the Sun travels under the rakia, and at night it travels above the rakia. And Gentile wise men say: during the day the Sun travels under the rakia and at night under the Earth. Rabbi [Yehudah Hanasi] said: their view is more logical than ours for during the day springs are cold and at night they are warm.

From this is discussion it is once again apparent that in the talmudic view, the sky must be completely opaque. As the Sun passes over the top of the sky at night, it is not in the slightest way visible.

Also from Landa, p63.

It is hardly news to point out that a long time ago people believed that the universe was different to the way that we understand it to be today. But the belief of the rabbis of the Talmud was standard until only very recently, by which I mean only a few hundred years.

Copernicus and his critics

When Nicolas Copernicus (d. 1543) proposed his heliocentric universe he did so for a number of mathematical reasons but without any evidence. The experimental evidence that supported his claim did not appear for over three hundred years, when in 1838 the first measurement of stellar parallax occurred. Without evidence to support the Copernican model, many rejected it. For example, the famous Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) rejected the Copernican model, and came up with one of his own in which all the planets orbited the sun, which in turn dragged them around a stationary earth. For about one hundred years after Copernicus, the universities of Oxford and Cambridge ignored the heliocentric model entirely, and the English philosopher, statesman, and member of Parliament Francis Bacon (1561–1626) rejected the Copernican model as having “too many and great inconveniences.”

Galileo and the Catholic Church

Galileo published his discovery of the four satellites of Jupiter in Sidereus Nuncius in 1610. This discovery did not prove that Copernicus was correct, but it lent a great deal of corroborative evidence to the Copernican model. In addition Galileo noted that Venus seemed to change shape, just as the Moon did, sometimes appearing almost (but never quite) full, sometimes as a semi-circle, and at other times as sickle-shaped. The best explanation was that Venus was not orbiting the earth, but that it was in fact orbiting the Sun. And that turned out to be correct too. But as we know, things didn't tun out to well for Galileo. The Catholic Church, which by now had placed Copernicus' book on its Index of Banned Books, also banned Galileo's Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems - the book in which he outlined his proofs that the earth orbited the sun. The works of the astronomer Johannes Kepler (d.1630) were also added to the Index.

The Jesuit Edition of Newton's Principa

In 1687 the Copernican model found support with the publication of Newton’s Principa Mathematica. In that work, Newton described the universal laws of gravitation and motion that were behind the observations of Copernicus, Galileo, and Kepler. The book went through three Latin editions in Newton’s life-time, and an English edition was published two years after his death in 1727. A new three-volume edition of the Principia was published in Geneva between 1739 and 1742. This edition contained a commentary on each of the book’s propositions by two Franciscan friars but was noteworthy for another reason. In its final volume, the “Jesuit edition” contained a disclaimer by the friars distancing themselves from the heliocentric assumptions contained in the book:

Newton in this third book assumes the hypothesis of the motion of the Earth. The propositions of the author cannot be explained otherwise than by making the same hypothesis. Hence we have been obliged to put on a character not our own. But we profess obedience to the decrees promulgated by sovereign pontiffs against the motion of the Earth.

The Rabbis believed what everyone believed

So it wasn't just the rabbis of the Talmud who believed the earth stood still. In fact they believed what (nearly) every one else continued to believe for at least a thousand years. The sun certainly looks like it revolved around the earth, so they created a model of the universe in which it did so, either by circling under the earth at night, or by zig-zagging back across the top of the rakia. Neither model turned out to be correct. But in believing this, the rabbis were firmly in the majority.

[If you want more on this subject, Natan Slifkin has an excellent monograph on the Path of the Sun at Night. I'm also told there's an excellent book on the Jewish reception of Copernican thought.]