Tomorrow we will read a bizarre and disquieting passage. In it, Yusteni, the grandchild of the Roman Emperor Antoninus, asked the great editor of the Mishnah, Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi at what age a girl is fit for intercourse as a means of betrothal, and at what age she may conceive a child. Let’s not attempt to identity this “Antonius,” (it is complicated) and focus on the reply. Rabbi Yehudah HaNasi thought that a girl may be betrothed by intercourse from the age of three years (and one day). However, he continued, she is incapable of conceiving until she is at least twelve years (and one day) old. To which Yusteni replied:

נדה מה, א

אני נשאתי בשש וילדתי בשבע אוי לשלש שנים שאבדתי בבית אבא

I married when I was six, and when I was seven I gave birth. Woe for those three years, between the age of three, when I was fit for intercourse, and the age of six, when I married, as I wasted those years in my father’s house by not engaging in intercourse.

Yusteni was not the only extremely young mother mentioned in the Talmud. In fact the Talmud in Sanhedrin (69b) entertains the possibility that a girl as young as six years of age could give birth to a child. And who could be the holder of such a record? It was Batsheva, the wife of King David.

“Batsheva gave birth when aged six

ובת שבע אולידא בשית”

Don't try this at home

Today we are going to do something that goes against a fundamental belief I have about Aggadah - (rabbinic stories and legends): that they should never be taken literally. Instead, we are going to take these two passages of Aggadah literally. They suggest that a girl as young as six (Batsheva) or seven (Yustenai) can give birth. Is this suggestion in any way scientifically possible? You might be surprised.

The Youngest Mother in the World

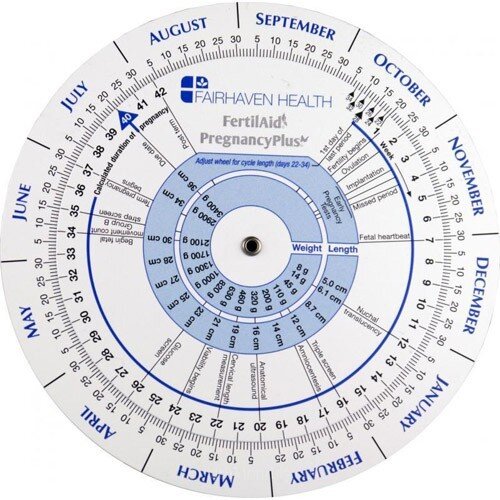

In May 1939 the French medical journal La Presse Medicale published a report from Lima about a little girl who had given birth to a baby at the age of only five years and seven months. Let me say that again. She had given birth to a baby when she was five years and seven months old. Putting aside the monstrous child abuse that is at the heart of this story (if that is even possible to do), let's focus on the pregnancy itself.

Report from La Presse Medicale, May 31, 1939. The complete original is here.

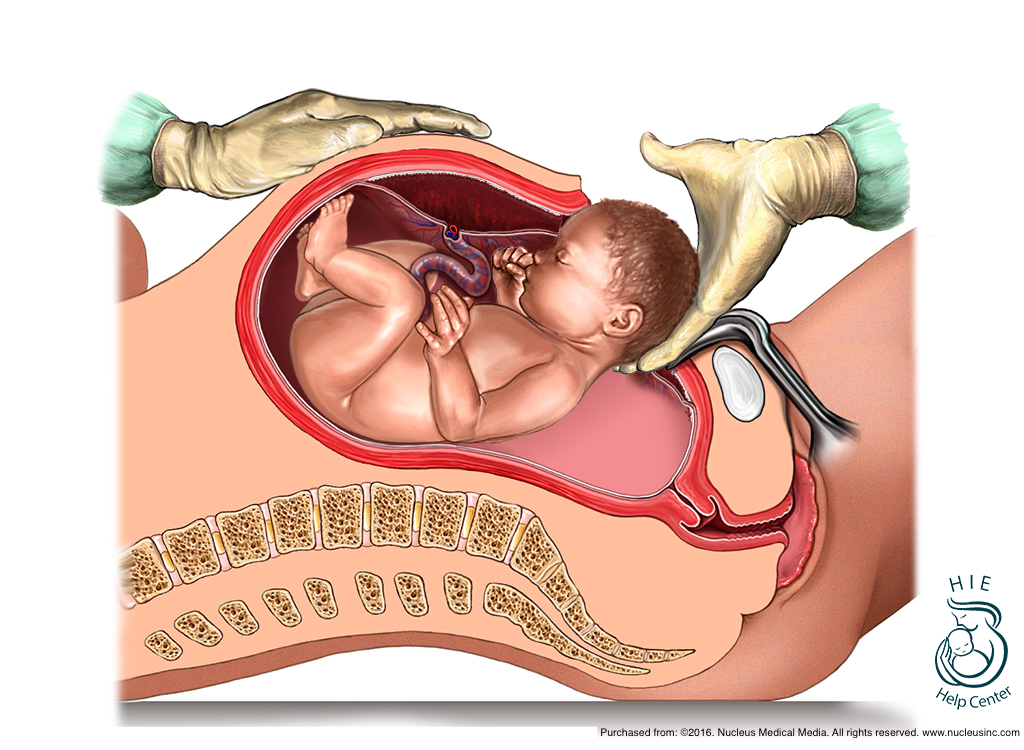

The little girl in the picture is Lina Medina, then five months pregnant. She lived in Peru, and her parents had brought her to a hospital fearing she had a tumor in her abdomen. Instead she was found to be pregnant, and six weeks later she gave birth by cesarian section to a healthy baby boy. She named her son Gerardo, after the chief physician Dr. Gerardo Lozada at the hospital where she was diagnosed. Her father was briefly arrested for child abuse but was later released. No charges were ever brought against her abuser, who Lina did not identify. Lina later married and had a second son in 1972.

The New York Times, November 15, 1939.p9.

How do we know the story is true?

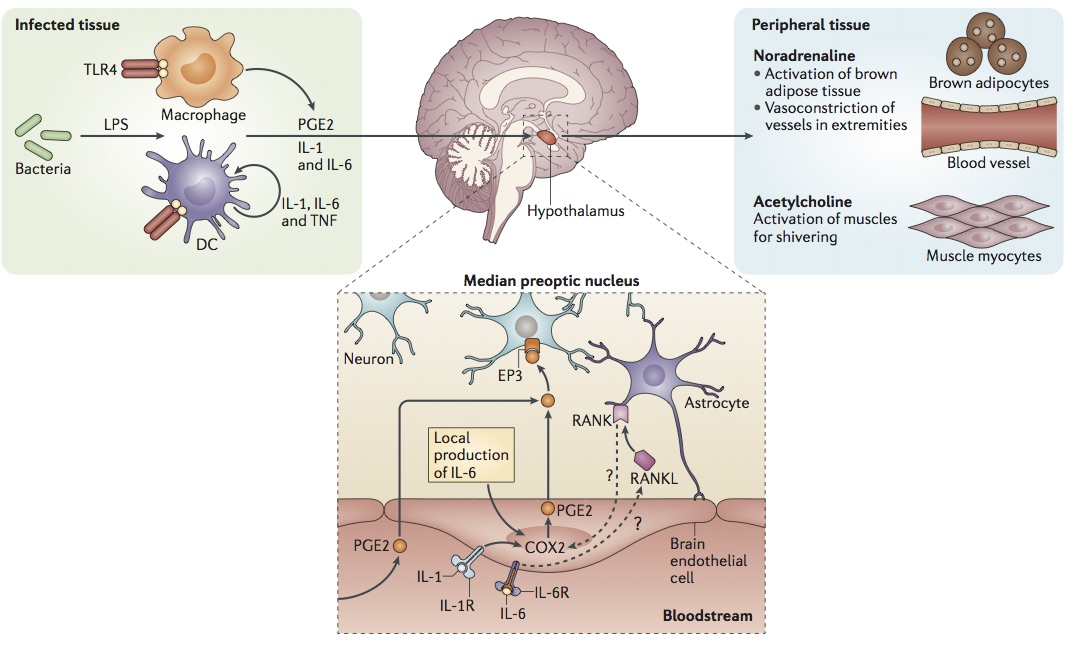

On November 15, 1939, The New York Times reported that the story had been authenticated by Dr S.L. Christian, the assistant surgeon general of the US Public Health Service. Christian had travelled to Peru, and while there he examined Lina. There is also a case report from Dr Edmundo Escomel on the pathology of one of Lina's ovaries that had been removed at the time of her cesarian section. (For those of you who are French speaking pathologists, you can read it here.) The report notes that Lina had the ovaries of a fully mature woman, and that she likely had a pituitary disorder that caused her precocious fertility. The story of Lina Medina has been authenticated by the fact-checking website Snopes, and there is a Wiki page about her (though having a Wiki page is not really proof of anything.)

Finally, there is a paper from a team at Hadassah Medical School in Jerusalem, published in Fertility and Sterility in 2009. The paper (titled At what age can human oocytes be obtained?) addresses the methods to remove and preserve eggs and sperm from young patients undergoing chemotherapy. "Increasing numbers of young cancer survivors" they wrote, "are experiencing infertility related to their past cancer treatment. Having children thus becomes an important issue for young cancer patients." One option to preserve fertility is to retrieve and preserve oocytes, which are the precursors to the ovum, the mature egg. The authors (who cite the pathology report on Lina Medina's ovary) report the successful removal of oocytes in girls ages 5, 8 and 10. This report from Hadassah is of the youngest age for ovarian oocyte retrieval, and demonstrates that even in girls who show no signs of menarche (the onset of menstruation), it is possible to find oocytes that can mature into eggs.

From Revel A. et al. At what age can human oocytes be obtained? Fertility and Sterility 2009; 92 (2):458-463.

Was Yustenai different, or lying?

Avraham ben Mordechai HaLevi (1650-1712) lived in Egypt and served as the senior rabbi in Cairo. In his work Gan Hamelech (The Garden of the King), he commented on the passage about Yustenai. He noted that the Talmud has two responses to her claim. The first suggests that the ability to have a child at the tender age of seven was limited to Gentiles. The Talmud cites a prooftext from Ezekiel (23:20)”for their flesh is the flesh of donkeys,” although it is unclear how that might prove anything. The second suggestion is that Yustenai was simply not telling the truth. This implies that it is simply not possible to conceive and carry a child at such a young age. The sage from Cairo rejected the second possibility, and found the claim of Yustenai to be plausible, but one was not biologically possible for a Jewish woman.

His conclusion was rejected by another Jewish scholar, Chayyim Yosef Dovid Azulai (1724-1806) known as the Chida. In his commentary on the Talmud called Petach Einayim the Chida thought that Yustenai’s story was simply implausible. He therefore supported the second possibility brought by the Talmud, which cited as a prooftext a verse from Psalms (144:8) “Whose mouth speaks falsehood, and their right hand is a right hand of lying.”

Neither sage was completely correct. We now know that there is absolutely no biological difference between Jews and Gentiles, so that means Avraham HaLevi’s conclusion is mistaken. And we also know that it is indeed possible for a girl of six or seven to conceive and carry a child. Just ask Lina Medina, who was younger than six when she gave birth. So Yustenai need not have been lying.

Back to Yustenai and Batsheva

It would appear that it is indeed possible for Yustenai, a first grader, and Batsheva, barely be out of kindergarten, to have given birth at age six or seven. Today, their abusers would be arrested and locked up for a very long time. How fortunate are we not to have to take these talmudic stories literally, even if they are regrettably, entirely plausible.

“The first group…accept the teachings of the sages in their simple literal sense and do not think that these teachings contain any hidden meaning at all. They believe that all sorts of impossible things must be... They understand the teachings of the sages only in their literal sense, in spite of the fact that some of their teachings when taken literally, seem so fantastic and irrational that if one were to repeat them literally, even to the uneducated, let alone sophisticated scholars, their amazement would prompt them to ask how anyone in the world could believe such things true, much less edifying. The members of this group are poor in knowledge. One can only regret their folly. Their very effort to honor and to exalt the sages in accordance with their own meager understanding actually humiliates them. As God lives, this group destroys the glory of the Torah of God and say the opposite of what it intended.

”

[Mostly a repost from here.]