Of all the medieval illuminated Haggadot that exist, the Sarajevo Haggadah is perhaps the most famous. It is thought to have been created in Barcelona around 1350, and today it is on display at the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina. If you are thinking of visiting it at the museum, plan ahead. The Haggadah is on display Tuesdays and Thursdays, and first Saturday of the month from noon to 1pm. You may visit at other times, if you pony up more money and let them know in advance. According to the Museum, the Haggadah is "its most valuable holding," and for good reason. It has three sections: the first has 34 full page small biblical illuminations from the creation of the world to the death of Moses. The next is the text of the traditional Haggadah, and the last section contains poems and readings to be read on each of the seven days of Passover. The illustrations are masterpieces in miniature; deep indigo and red across a golden background, with elegantly elongated Hebrew letters that seem to drip down the page. It is in every way, the gold standard of Haggadot.

The remarkable History of the Sarajevo Haggadah

We know little of the first five-hundred years of the Haggadah. The name of the original owner is not known, and it appears to have been taken out of Spain in 1492, when Jews were expelled by the Alhambra Decree. There is a note written by a Catholic priest, Giovanni Domenico Vistorini, who inspected the Haggadah in 1609 for any anti-Christian content. Vistorini, who was most likely a converted Jew, found nothing objectionable in the Haggadah. "His Latin inscription, Revisto per mi (“Surveyed by me”)" wrote the Pulitzer Prize winning author Geraldine Brooks "runs with a casual fluidity beneath the last, painstakingly calligraphed lines of the Hebrew text." The Haggadah then disappeared for almost three centuries, until it was sold to the National Museum by a Joseph Kohen in 1894.

Dervis Korut saves the Haggadah

That the Sarajevo Haggadah had survived that long was highly improbable, but a series of even more unlikely events were to come. On April 16, 1942 the Nazis invaded Sarajevo and immediately destroyed the city's eight synagogues. The museum's chief curator was an Islamic scholar named Dervis Korut. He heard the Nazis were looking for the Haggadah to add to their proposed "Museum of an Extinct Race." Realizing the danger, he was smuggling the Haggadah out of the museum under his coat when he was summoned by the much feared General Johann Fortner, who demanded it. Geraldine Brooks picks up the story:

The museum director feigned dismay. “But, General, one of your officers came here already and demanded the Haggadah,” he said. “Of course, I gave it to him.."...

“What officer?” Fortner barked. “Name the man!”

The reply was deft: “Sir, I did not think it was my place to require a name.”

Korut eventually hid the Haggadah in the mosque of a small nearby village, where the Imam kept an eye on it and returned it at the end of the war. The Haggadah had been saved by two brave Muslims.

Whoever saves one human life...

“The man so determined to protect a Jewish book was the scion of a prosperous, highly regarded family of Muslim alims, or intellectuals, famous for producing judges of Islamic law.”

While the Koruts are best remembered for having saved the Sarajevo Haggadah, it is not this achievement of which the family is most proud. “In our family, the Haggadah is a detail,” his son said.“What my father did for Jewish people—that is the biggest thing that we, in our family, have to be proud of.”

In 1942, shortly after hiding the Haggadah, a sixteen-year-old girl named Mira Papo came to Korut and asked to be hidden. The family took her in, dressed her as a Muslim, and passed her off as their maid. Four months later they arranged for Mira to join her aunt at an area on the Dalmatian coast where there was no Nazi presence. She survived the war and later moved to Israel. And then, in 1994, Mira wrote a testimony of her rescue and submitted it Yad Vashem. Korut Dervis, who had died in 1969, and his wife Servet were added to the names of the Righteous Among the Nations. Servet received a certificate, a pension, and the right to Israeli citizenship.

Just when the story seemed to have reached its conclusion, another dramatic episode began. In 1999, at the height of the atrocities of the civil war in Kosovo, the Korut’s youngest daughter Lamija, and her Muslim husband were forced from their home by Serbian militiamen. They were sent to a refugee camp in which the conditions were so appalling that they were forced to flee. The couple were refused asylum by France and Sweden, and in desperation they turned to the small Jewish community of Skopje in Macedonia. Somehow, Lamija still had with her the certificate that Yad Vashem had given to her mother. She showed it to Victor Mizrahi, the president of the community, and four days later, Lamija and her husband landed in Tel Aviv. The Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, was at the airport to welcome them. “Today, we are closing a great circle in that the state of Israel, which emerged from the ashes, gives refuge to the daughter of those who saved Jews,” he said. And then, in the chaos of the media frenzy at the airport Lamija heard someone calling her in Serbo-Croation.

“It was a good feeling, to have someone speaking your language,” she said. But she had no idea who it could be, greeting her so warmly. Pushing through the crowd was a slender, wiry man she had never seen before, with a shock of dark hair and a mustache. Opening his arms, he introduced himself, and Lamija fell into the embrace of Davor Bakovic, the son of Mira Papo.

The Haggadah is restored

It's a remarkable story, which I hope you will share at your Pesach Seder when you reach the passage שפיך חמתך על הגוים - "pour out Your wrath on the Gentiles who do not know You..." But having taken a deep breath and dried our eyes, let's return to the Haggadah itself. In her 2008 novel The People of the Book, Geraldine Brooks opens in Sarajevo, where, under the watch of staff from the United Nations and security officers from the State Museum, an Australian conservator works on the Sarajevo Haggadah.

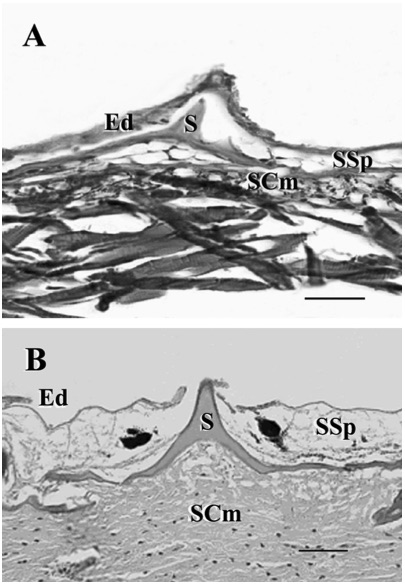

Pataki at work repairing the Sarajevo Haggadah. Photo courtesy of Andrea Pataki.

In fact the real Hagaddah did undergo conservation, but it was carried out by Andrea Pataki, from Stuttgart, Jean-Marie Arnolt of Paris, and the late Prof. Bezalel Narkiss, Professor Emeritus of Art History at the Hebrew University. These three experts wrote of their experience in conserving the Haggadah in a paper published in The Paper Conservator in 2005. For those of you who let your subscription lapse, you can find a copy here.

Andrea Pataki is a book conservator of world renown. For almost a decade she led the Studiengang für Papierrestaurierung, the Book and Paper Conservation Program at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Stuttgart, before taking up her present position as a professor at the Technical University of Cologne. Pataki is not Jewish, but had lost Jewish relatives in the Holocaust. Recalling her own role in the project, she never considered it significant that she was a Gentile born in Vienna now repairing a manuscript once pursued by the Nazis. Instead, she noted that she was hired because of her expertise and experience. Her own background was of little consequence. And that is how it should be.

In December 2001 Pataki spent nine days repairing the Haggadah at the Union Bank in Sarajevo. Each day, she recalled later in in an academic paper,

... the manuscript was brought to the 'conservation lab' in its metal box which was opened by representatives of the Museum. Working hours were from 8:00 am to 4:00 pm, after which the manuscript was locked in its box and promptly returned to the vault of the Union Bank. As a consequence, it was necessary to stop treatment each day at a stage at which the manuscript could be closed and put away safely.This meant making sure that all repairs would have adequate time to dry during the day, which required a great deal of planning and foresight.

Pataki found that the original covers of the Haggadah, which had certainly been made of vellum, were lost. In their place were cheap cardboard covers in a Turkish floral design, which were entirely orthogonal to the style of the Haggadah. Several sections, called quires, were detached from the rest of the book and needed to be carefully sewn back into place. The book joints, where the outer boards of the cover meet the spine, had broken. This allowed Pataki access to the binding underneath. She repaired one of the four cords that ran vertically down the spine and around which the quires are sewn. The joints were reattached. Finally, she repaired the head a tail caps at the top and bottom of the spine with new calf leather that had been specially dyed for this restoration.

Of all the damage that the Haggadah had suffered, none was more important than the wine stains, just like those found on the pages of family Haggadot to this day. Here is Pataki’s assessment:

The ritual of washing the hands twice during the ceremony had resulted in water stains on the parchment and smudges and smearing of pigments. The ceremony also calls for the drinking of four cups of wine and consumption of different foods dipped in salt water, before and during the festive meal. This activity resulted in many stains and discoloured areas on the pages which call for ritual drinking and eating…

What was to a conservator a sign of damage and discoloration was to the Jewish community a symbol of continuity. The stains were a testament that the Sarajevo Haggadah had not been left on a shelf, but had been used at the table, guiding the Seder night for hundreds of years.

“Due to the use of the manuscript on the Passover table for many generations, the main damage to the text-block had been caused by liquid. ”

The Sarajevo Haggadah as a symbol of Tolerance and Hope

Neal Kritz, a lawyer at the United States Institute for Peace, was in Sarajevo in the late 1990s. He was part of a delegation that focused on the restoration of the justice system and the atrocities that had occurred during the Bosnian civil war. Kritz recalled how the Bosnian Serbs had demanded the Sarajevo Haggadah be displayed in Banja Luka, the de facto capital of the newly created Serb republic. It was their treasure too, they claimed; it did not just belong to the people of Bosnia-Herzegovina. Their demands were rejected, and the Haggadah remained in Sarajevo, where a new display of it opened there only last month. Kritz received a token of gratitude from the Chief Prosecutor of the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovnia. It was, of course, a facsimile edition of the Sarajevo Haggadah, which had now come to symbolize efforts to make peace between Bosnians and Serbs. And in November 2017, UNESCO added the Sarajevo Haggadah to their Memory of the World Register to mark, naturally, the International Day for Tolerance.

Over the last seventy years the Sarajevo Haggadah has twice been saved. First, two Muslims risked their lives to rescue it from those who sought to annihilate the Jewish people. And then it was saved from the ruins of time by an expert from the very country from which so much hate had originated. The last word goes to Mirsad Sijarić, the Director of the National Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina: "The Sarajevo Haggadah is physical proof of the openness of a society in which fear of the Other has never been an incurable disease."