In today's page of Talmud there is a dispute about how far the prohibition against idol worship extends:

עבודה זרה נא, א

שחט לה חגב ר' יהודה מחייב וחכמים פוטרים

If one slaughtered a locust for an idol, Rabbi Yehuda deems him liable, and the Rabbis deem him exempt from punishment.

According to Rabbi Yehudah the neck of the grasshopper is similar to the neck of an animal; since slaughtering an animal for idol worship is prohibited, so, by analogy, is slaughtering a grasshopper.

ושאני חגב הואיל וצוארו דומה לצואר בהמה...

The neck of the grasshopper resembles the neck of an animal...

What is a neck?

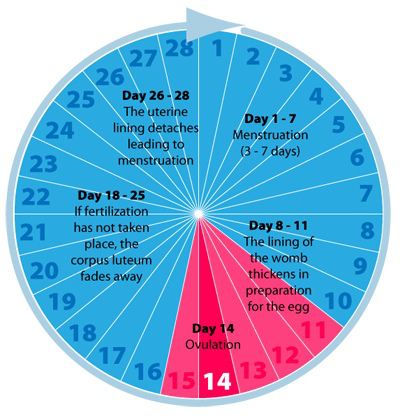

The neck is the bit that connects an animal's head to its body. Grasshoppers have a head and they have a body, so perforce, they have a neck. Here is what a typical (female) grasshopper looks like:

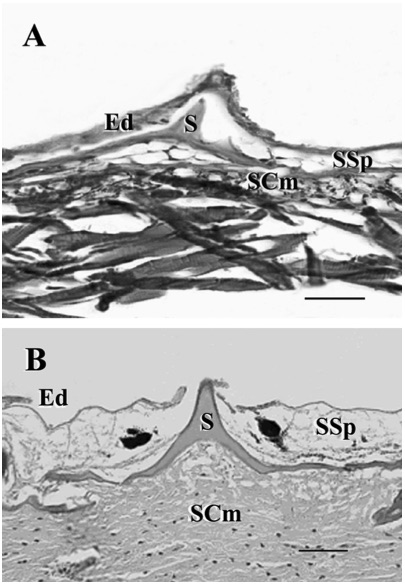

As you can see, the pronotum sits where the neck should be. It is the bony upper plate of the first section of the thorax, and when viewed from the side, appears saddle shaped. Other insects with a pronotum include ladybugs (or ladybirds, as they are quaintly called in Britain and elsewhere), termites, beetles and fleas. The pronotum covers the cervix, the neck proper, which is "a membranous area that allows considerable freedom of movement for protraction and retraction of the insect's head." Like all insects, grasshoppers possess an exoskeleton. Beneath this hard outer shell, lay all the soft squishy bits like the gut and heart, or at least what passes for a heart in an insect.

Rabbi Yehudah's Anatomy Lesson

Rabbi Yehudah declared that the neck of the grasshopper resembled the neck of an animal, by which he meant an animal that was offered as a sacrifice in the Temple. Rashi changes the language just a little, and in so doing suggests the resemblance is even closer. The grasshopper's neck does not just resemble (דומה) an animal's. Rather, they are the same:

דיש לה צואר כבהמה ולהכי מחייב רבי יהודה דכעין שחיטת פנים הוא

The grasshopper has a neck like an animal, which is why Rabbi Yehudah finds that [a person who slaughters a grasshopper like he would an animal] is liable...

Here is the explanation found in the Koren English Talmud:

Most insects possess a head located very close to the body, i.e., the thorax, and therefore lack a visible neck. Nevertheless, some types of grasshopper possess an uncommonly visible pronotum protecting the front of the thorax. This feature has the appearance of a neck, and so even though a grasshopper cannot be truly slaughtered, it can appear to be slaughtered much like animals with necks.

But animal necks and grasshopper necks are nothing like each other.

The grasshopper neck:

- Is covered with a protective shell (the pronotum)

- Does not possess an endoskeleton.

- Is really the cervix which lies hidden beneath the pronotum.

The animal neck:

- Is covered with skin or feathers, not a hard protective shell.

- Has an endoskeleton made of seven cervical vertebrae.

- Is clearly visible and is not hidden.

It is not clear in what way Rabbi Yehudah equated the neck of a grasshopper with the neck of an animal that was sacrificed in Jerusalem, but his teaching is echoed in Jewish law. According to Maimonides, such an act is forbidden if it is done as a part of a religious ceremony:

משנה תורה, הלכות עבודה זרה וחוקות הגויים ג׳:ד׳

שָׁחַט לָהּ חָגָב פָּטוּר אֶלָּא אִם כֵּן הָיְתָה עֲבוֹדָתָהּ בְּכָךְ

And the Shulchan Aruch rules that a grasshopper slaughtered in front of an idol, regardless of whether this was part of a religious ceremony or not, is forbidden to be used by a Jew.

שולחן ערוך ירוה דעה ס׳קלט, ד

שחט לפניה חגב, נאסר, אפלו אין דרך לעבדה בחגב כלל

As a result, it's probably best not to sacrifice a grasshopper to an idol, even if you can't see its neck.