בבא קמא כד, ב

ת"ש שיסה בו את הכלב ... פטור מאי לאו פטור משסה וחייב בעל כלב? לא אימא פטור אף משסה אמר רבא אם תמצי לומר המשסה כלבו של חבירו בחבירו חייב שיסהו הוא בעצמו פטור מאי טעמא כל המשנה ובא אחר ושינה בו פטור

Come an hear [a proof from a Mishnah in Sanhedrin]:

If one incited a dog [against another person]...he is not liable. Who is "not liable"? Does this mean that the inciter is not liable, but that the dog's owner is liable? No. Say that this Mishnah means that even the one who incites is not liable. Rava said the following: Even if you conclude that when a person incites a dog against his fellow, [that the owner is liable], if the victim incited the dog against himself, [and brought the attack upon himself, then in this case the dog's owner] is also not liable. What is the reason for Rava's ruling? Because whenever a person acts in an irregular way, and another person comes along and acts in an irregular way against him, [the second party] is not liable.

JEWS AND DOGS

From this passage in today's daf yomi, we learn a couple of things about dogs in the period of the Mishnah. First, we learn that Jews, or those who interacted with Jews, kept them. And second, that some of them were very bad dogs.

Jews and dogs don't traditionally get along. Later in our tractate, (Bava Kamma 83a,) Rabbi Eliezer does not mince his words:

רבי אליעזר הגדול אומר: המגדל כלבים כמגדל חזירים .למאי נפקא מינה? למיקם עליה בארור

Rabbi Eliezer the Great said: Someone who breeds dogs is like someone who breeds pigs. What is the practical outcome of this comparison? To teach that those who breed dogs are cursed...

The American Veterinary Medical Association estimates that in the US there are about 43 million households that own almost 70 million dogs; that means over one-third of the households in the US own a dog. (Fun Fact: Cats are owned by fewer households in the US, but are more often owned in twos or more. That means that there are more household cats - some 74 million - than there are dogs.) In the UK, a 2007 study estimated that 31% of all households owned a dog. In Israel, over 10% of all families own a dog.

BAD DOGS

Most dogs are wonderful pets, but a few are really bad. In a 10 year period from 2000-2009, one paper identified 256 dog-bite related fatalities in the US. Of course that's a tiny number compared to the overall number of dogs owned, but that's still 256 too many; the tragedy is compounded when you read that over half the victims were less than ten years old.

Partaken, GJ. et al. Co-occurrence of potentially preventable factors in 256 dog bite–related fatalities in the United States (2000–2009). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 2013. 243:12: 1726-1736.

“Az a yid hot a hunt, iz oder der hunt keyn hunt nit, oder der yid iz keyn yid nit

If a Jew has a dog, either the dog is no dog, or the Jew is no Jew”

Although fatalities from dog bites are rare, dog bites are not. Over my career as an emergency physician I must have treated hundreds of patients with dog bites. And my experience is pretty typical. One recent study estimated that more than half the population in the US will be bitten by an animal at some time, and that dogs are responsible for 80-90% of these injuries.

GOOD DOGS

Although Jews are thought not to have a historical affinity for dogs, one theologian has reassessed the evidence. In his 2008 paper Attitudes toward Dogs in Ancient Israel: A Reassessment, Geoffrey Miller suggests that in fact dogs were not shunned in Israelite society. He notes that the remains of over a thousand dogs were discovered in a dog cemetery near Ashkelon dating from about the 5th century BC. It was described as "by far the largest animal cemetery known in the ancient world" by Lawrence Stager who also pointed out that during this period, Ashkelon was a Phoenician city - not a Jewish one. Miller surveys several mentions of dogs in the Bible and the Book of Tobit, and concludes that at least some Israelites "valued dogs and did not view them as vile, contemptible creatures." Joshua Schwartz from Bar-Ilan University surveyed Dogs in Jewish Society in the Second Temple Period and in the Time of the Mishnah and Talmud (a study that marked "...the culmination of several years of study of the subject of dogs..."). He found that while "most of the Jewish sources from the Second Temple period and the time of the Mishnah and Talmud continue to maintain the negative attitude toward dogs expressed in the Biblical tradition" there were some important exceptions. There were sheep dogs (Gen. Rabbah 73:11) and hunting dogs (Josephus, Antiquities 4.206) and guard dogs (Pesahim 113a), and yes, even pet dogs (Tobit, 6:2), though Schwartz concedes that "it is improbable that dogs in Jewish society were the objects of the same degree of affection as they received in the Graeco-Roman world or the Persian world."

“A certain person invited a sage to his home, and [the householder] sat his dog next to him. [The sage] asked him, ‘How did I merit this insult?’ [The house-holder] responded, ‘My master, I am repaying him for his goodness. Kidnappers came to the town, one of them came and wanted to take my wife, and the dog ate his testicles.”

Liability for Dog Bites in the US

In contrast to the talmudic rule requiring three occurrences of goring or biting before an animal is considered "forewarned" and so liable to pay full damages, many states have a "one bite and you're out rule". But New York, for example has a law that has aspects of the talmudic category of mu'ad, at least according to this opinion:

New York Agriculture & Markets Code section 123 (part of the Laws of New York) addresses a dog owner's potential civil liability when the owner's dog injures another person. The statute covers both injuries caused by bites and non-bite injuries, like those suffered when a dog knocks a person to the ground. The statute states that the owner of a "dangerous dog" is liable if the dog causes injuries to another person, to livestock, or to another person's companion animal, like a disability service dog.

The statute defines a "dangerous dog" as one that:

- attacks and either injures or kills a person, farm animal, or pet without justification, or

- behaves in a way that causes a reasonable person to believe that the dog poses a "serious and unjustified imminent threat of serious physical injury or death."

However, the statute specifically states that a law enforcement dog carrying out its duties cannot be considered a "dangerous dog."

Under New York's "dangerous dog" statute, a dog owner is "strictly liable" for all medical bills resulting from injuries caused by a "dangerous dog." This means that if the dog is found to be dangerous, the dog's owner must pay the injured person's medical bills (or bills for the treatment of injuries to livestock or pets) even if the dog's owner had taken reasonable precautions to control or restrain the dog. For other types of damages resulting from a dog bite or dog-related injury, the injured person must usually prove that the dog's owner was negligent. In other words, the injured person must show that the dog's owner failed to use reasonable care to prevent the injuries from occurring (failed to take reasonable steps to control or restrain the animal, in other words). For example, suppose that a dog slips out of its own yard, breaks down the neighbor's fence, and enters the neighbor's yard, where it bites the neighbor. While the injured neighbor may be able to recover the costs of medical care under New York's strict liability rule, the neighbor cannot recover the costs of replacing the broken fence unless the neighbor can show that the dog's owner failed to take reasonable steps to keep the dog in its own yard.

The legal category of mu'ad - an animal (or more precisely here, a dog) that was forewarned as being a danger is clearly noted in New York Agriculture & Markets Code section 123. The law allows charges to be filed if:

- the dog was previously declared to be a "dangerous dog"

- the owner negligently allows the dog to bite someone, and the injury suffered is a "serious injury."

If a "dangerous dog" overcomes an owner's attempts to restrain it and kills a person, the owner may also be charged with a misdemeanor. Any owner who faces a criminal charge relating to a dog bite might also face civil liability if the injured person decides to sue in civil court.

Here's how the lawyer Mary Randal explains the factors that courts take into account when deciding if a dog owner is liable for the damages of a pet. See how many times there is an echo to the talmudic concept of mu'ad:

Previous bites. This one is pretty easy. If a dog bites once, the owner will forevermore be on notice that the dog is dangerous. But even this is not as straightforward as it may appear; for example, at least one court has ruled that if a puppy nips someone, its owners are not necessarily on notice that the dog is dangerous. (Tessiero v. Conrad, 588 N.Y.S.2d 200 (App. Div. 1992).)

Barking at strangers. If a dog, usually kept in the house or a fenced yard, barks at strangers but has never threatened a person, its owners will probably not be liable if it bites someone. (See, for example, Slack v. Villari, 476 A.2d 227, cert. denied, 482 A.2d 502 (Md. 1984) and Collier v. Zambito, 1 N.Y.3d 444 (2004).)

Threatening people. A dog that often growls and snaps at people who come near it when out in public, but hasn't ever actually bitten someone, is a different case entirely. The dog's actions should put its owner on notice that the dog might bite someone. If the dog does bite, the owner will be liable. (See, for example, Fontecchio v. Esposito, 485 N.Y.S.2d 113 (1985).)

Jumping on people. The owner of a friendly, playful, and large dog, which is in the habit of jumping on house guests, will be liable if the exuberant dog knocks over a friend who comes to the door one day. The owner knew that the dog behaved this way and might injure someone because of its size.

Frightening people. If a dog likes to run along the fence that separates his yard from the sidewalk barking furiously, or chases pedestrians or bicyclists, the owner may be liable if the dog causes an injury. At least one court, however, has ruled that an owner wasn't responsible for foreseeing that a barking dog could frighten someone so much she would run into the street. (Nava v. McMillan, 123 Cal. App. 3d 262 (1981).)

Fighting with other dogs. If a dog that is gentle with people has a history of fights with other dogs, that's probably not enough to put the owner on notice that the dog might bite a person. Courts usually recognize that canine society has its own rules, and the way a dog behaves under them isn't a reliable predictor of how it will act toward humans. (As one court put it, the “question was the dog's propensity to attack a human. The canine code duello is something else. That involves the question of what constitutes a just cause for battle in the dog world, or what justifies a resort to arms, or rather to teeth, for redress.” (Fowler v. Helck, 278 Ky. 361 (1939).)

Fight training. If a dog has been trained to fight, a court will almost certainly conclude that the owner should have known that the dog is dangerous. (This conclusion is disputed by some people experienced with dogs used for fighting, who maintain that there is no connection between a dog's drive to fight other dogs and its aggression toward people. However, a dog that has been agitated and abused when used for fighting may be dangerous.)

Complaints about the dog. If neighbors or others complain to the owner that a dog has threatened or bitten someone, the owner would certainly be on notice that the dog is dangerous. But in one Alabama case, where a dog's owner had been scolded by a neighbor for having a dog that was a "nuisance," the court ruled that the owner did not have any knowledge that his dog was dangerous. (Rucker v. Goldstein, 497 So. 2d 491 (Ala. 1986).)

The dog's breed. Generally, courts don't consider dogs of certain breeds to be inherently dangerous. So if you have a German shepherd, a court probably won't conclude that you should have known, just because of the dog's breed, that it might injure someone. (See, for example, Roupp v. Conrad, 287 A.D.2d 937, 731 N.Y.S.2d 545 (2001).) But in some places, pit bulls and a few other breeds have been defined by law as dangerous dogs.

VERY GOOD DOGS

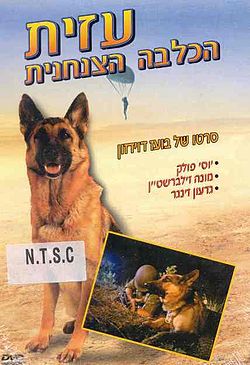

Whatever your feeling about dogs, lets's be sure to remember that they serve alongside soldiers in the IDF, where they save lives. In 1969, Motta Gur (yes, the same Mordechai "Motta" Gur who commanded the unit that liberated the Temple Mount in the Six Day War, and who uttered those immortal words "The Temple Mount is in our hands!" הר הבית בידינו,) wrote what was to become a series of children's books called Azit, the Canine Paratrooper (later turned into a popular feature film with the same title. And now available on Netflix. (Really. It is available on Netflix.) But IDF dogs don't just feature in fiction. They are a fact, and an amazing addition to the IDF, where they make up the Oketz unit. Here's a news report (in Hebrew) about the amazing work these dogs - and their handlers- perform. These are very good dogs indeed.